A version of this sermon was preached at the First Baptist Church of Hyattsville on Sunday, December 6, 2015. The Scripture texts were Malachi 3.1-4 and Luke 1.67-79. Accompanying the biblical texts was a reading of Langston Hughes’ 1930 poem, “Merry Christmas”

As December begins, and our thoughts turn earnestly toward Christmas, this is how we like to think of Jesus.

But sadly, in too much of the world, too many people are seeing Jesus the way these Egyptian women see Jesus in the photograph below: splattered and stained just like everyone and everything else, covered in the violence that has become all too common – so common, in fact, that some commentators have begun referring to it as “the new normal.”

This photograph was taken in Egypt a few years ago, but it easily could have been taken in America a few days ago. We no longer have to look overseas to grieve senseless acts of violence or contemplate the theological questions associated with them. 2015 is the year in which the phrase “active shooter” entered our vocabulary, and this is the context in which we come to church on this second Sunday of Advent to light the Candle of Peace.

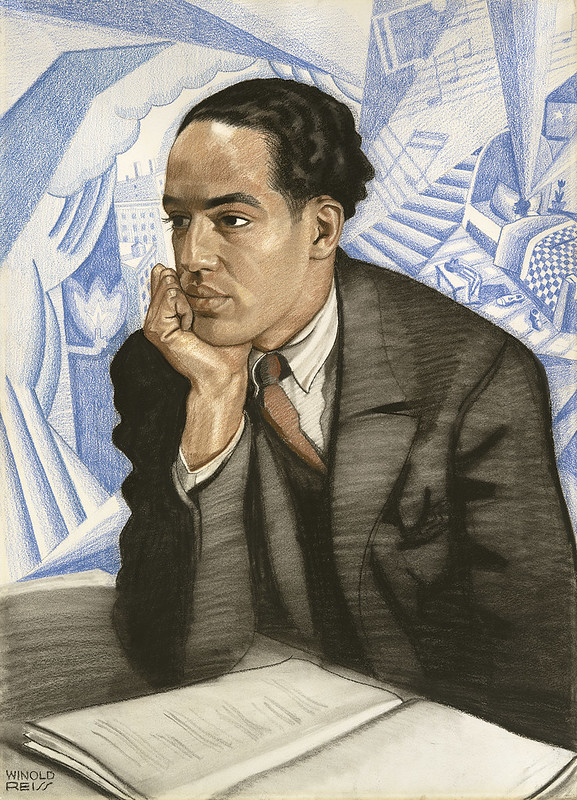

This context is why we need to hear Langston Hughes’ ironically titled poem, “Merry Christmas,” alongside “Silver Bells,” “White Christmas,” “Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire,” and the other seasonal standards this year. It’s challenging to hear, I know. You might have even found it offensive. But that’s precisely why we need to hear it. These challenging words from a poet of the Harlem Renaissance call us closer to what the gospel story of Christmas has to say to us.

Now, you may be thinking to yourself: hang on a second, preacher. Angels and shepherds and a star and a manger – this is the gospel story of Christmas. That’s what we read about in the Bible. That’s what Linus tells Charlie Brown Christmas is all about. And you’d be right – it is. But it’s not all we read about in Luke, much less the Bible.

Linus begins his story with Luke 2. However, as the people of Jesus, we have to begin with Luke 1. And Luke 1 doesn’t begin the story of Christmas with angels or shepherds or stars or mangers. Luke doesn’t even begin with Jesus. Luke 1 begins with John the Baptist. The presence of John the Baptist is how you know you’re dealing with the full gospel version of Christmas, because John the Baptist is the context for the angels and the shepherds and the star and the manger.

Funny how you never see a John the Baptist lawn ornament, now, isn’t it?

Actually, the lack of inflatable, light-up John the Baptists is completely understandable because the truth is we don’t like to start with him, either. Not only is John the Baptist a freaky dude who walks around wearing camel’s skin and snacking on locusts, he’s a freaky dude who comes, in the words of Malachi, to prepare the way of the Lord – which means he comes like a refiner’s fire, like fuller’s soap – to proclaim the need for cleansing and purifying as he goes. He comes to preach repentance. And he comes to Judea – to God’s people. He’s not strolling the streets of Rome, or Damascus, or Baghdad. He’s not coming to get in the face of “those people.” He’s coming to get into our face – in much the same way Langston Hughes gets in our face, pointing out things we don’t want to hear, much less see.

One of the most uncomfortable aspects of this poem is that, even though it was first published 85 years ago, it hardly reads like a relic of the past. Too much of this of this poem is all too familiar, because this is hardly the first year in America we’ve lit the Candle of Peace in the shadow of violence and terror – and not only violence done to us, but violence done by us. That’s the uncomfortable truth Langston Hughes is pointing out – the same kind of truth John the Baptist comes to point out – because that’s the kind of truth we have to confront if we are to repent.

It’s the kind of truth we’ll hear from Jesus, too.

So, if this poem offends you, or makes you squirm, and you don’t want to squirm or be offended, then I suggest you stick with “the holly jolly” commercial version of Christmas – because if Langston Hughes ruffles your feathers, then John the Baptist is liable to make ‘em fall out completely. In fact, you might want to consider heading over to the mall next Sunday morning, because we’re going to be reading more about J.B. next week, too. (FYI – The Mall at Prince George’s Plaza opens at 8:00 a.m., and I promise they’ll go out of their way not to offend you). Just know that if you decide to come to church, and if you look deep into the full gospel version of Christmas within the pages of Scripture, and if you truly have ears to hear and you hear, then chances are you’ll be offended. And you’ll be offended because God’s in the business of being offensive.

“if you look deep into the full gospel version of Christmas within the pages of Scripture, and if you truly have ears to hear and you hear, then chances are you’ll be offended. And you’ll be offended because God’s in the business of being offensive.”

“

It was offensive for God to lower a sheet filled with unclean animals before Peter – animals he had never touched in his entire life – and say, “Kill and eat.”

It was offensive for the Spirit to tell Phillip to get in the carriage with the Ethiopian eunuch, an unclean Gentile of the first order.

It was offensive for the prophets of old to declare to the tribes and kings of Israel how the smell of their burnt offerings turned God’s stomach.

It was offensive for Jesus to tell the rich young ruler to give away all that he had.

It was offensive when Jesus to tell Martha, you know what, it’s okay that Mary is taking a break from her chores to sit and listen. In fact, she’s made a better choice than you have.

It was offensive when Jesus told the Pharisees it’s was okay to pick grain on the Sabbath because the Sabbath was created for people, people weren’t created for the Sabbath.

It was offensive when Jesus, the King of kings, the long-expected Messiah, deigned to wash His disciples’ feet – and to declare that they had no share in Him if they refused.

It was offensive when this same Messiah secured our salvation by being crucified like runaway slave. That’s why Paul declares that Christ crucified is a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles.

The gospel is offensive, plain and simple. It has to be offensive if it’s to do us any good. Offending our sensibilities for the sake of grace, defying decorum in the interest of justice – this is how God reminds us that He is God and we are NOT. It’s how God in Christ points out to us those jagged, cumbersome, unsightly logs that jut out of our own eyes when what we’d rather do is obsess over the speck we notice in our neighbor’s eye. Being offensive is how God confronts us in order to transform us. It’s the only way, really, that He can heal the world – by forcing us to acknowledge our wounds, as well as the wounds we inflict on others.

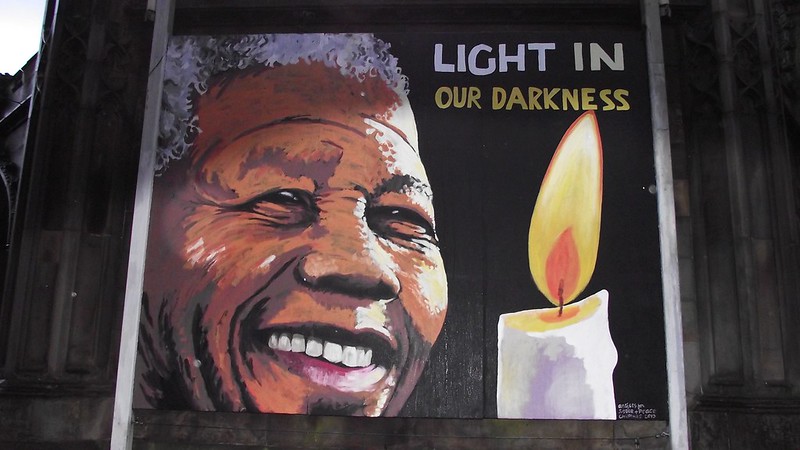

In fact, acknowledging those wounds is the only way we can light the Candle of Peace with any integrity today. For, if we fail to acknowledge our wounding and our woundedness, then we light this candle as false prophets – declaring peace, peace where there is no peace.

But if we approach the Advent Wreath, if we look toward the manger, with contrite and repentant hearts, then it becomes a powerful symbol indeed. If we approach the Advent Wreath with contrite and repentant hearts, then we light this Candle of Peace not in delusional ignorance of the violence and the division and the injustice of the world but indefiance of it.

With contrite and repentant hearts, we light this candle as people ready to shoulder our crosses and follow where Jesus will lead.

With contrite and repentant hearts, we light this candle as people who remember that when Jesus scandalously got down on His hands and knees to wash His disciples’ feet, He set an example for us. And when we remember the example Jesus has set for us, we position ourselves to proclaim that Jesus really is “the reason for the season” in ways that don’t ring hollow in the ears of observant people like Langston Hughes, who see the world plainly and who aren’t fooled by window dressing.

Proclaiming Jesus with integrity is what we must do, because the world needs what the full gospel version of Christmas has to offer. The world needs to see and experience the glory of this holy season, to know that in Christ God is coming to His temple. Heaven is coming to earth. God is coming to walk in our shoes and live in our flesh, because God is willing to be splattered and stained by all the muck and the mire, the blood and the gore that the machines of worldly power spew out. He’s willing to wade directly into the cycles of violence that wreak havoc on our bodies and our souls and in our communities so that all of creation might yet be redeemed. And if we are His people, then Jesus calls us to wade right in there with Him, to be instruments and agents of His peace – the peace that surpasses all understanding, because it won’t let us settle for the false comfort of social conventions, preconceived notions, and self-righteous piety.

“God is coming to walk in our shoes and live in our flesh, because God is willing to be splattered and stained by all the muck and the mire, the blood and the gore that the machines of worldly power spew out.”

Joining Christ in that work is how God will ultimately “guide our feet into the way of peace,” because peace is more than a feature of life. It is a way of life. Peace is a work to be fashioned rather than a present to be received. Blessed are the peacemakers, Jesus said, not blessed are the peaceful.

So, in the interest of “the way of peace,” let me leave you today with some provocative, if not offensive, questions:

What would the world look like if we, the people of Jesus, recruited for peace with the same intensity that ISIS recruits for terror?

What would the world look like if we, the people of Jesus, prepared for ministry with the purpose and intentionality of the “active shooters” who prepare so meticulously for their heinous acts of violence?

What would the world look like if we, the people of Jesus, waged peace as earnestly and systematically as the world’s armies wage war?

I think we would find it to be a world in which Christmas, and all the seasons before and all the seasons after, would be very merry indeed.

May we have faith and courage to shoulder our crosses and follow Jesus into the way of peace. Amen.