All parents have certain stories they tell about their children. I certainly have stories I tell about mine. One of the stories my mom tells about me involves my first trip to Wendy’s. This would’ve been the early 1980s when the “Where’s the Beef?” campaign was all the rage. I thought those hamburgers looked so good on TV – much better than my usual Happy Meal burger. I really wanted to try one, so my mom took me to Wendy’s one evening. As she tells it, I was giddy with excitement standing in line. I waited with great anticipation as they got our order ready. Then we found a seat at one of those tables that looked like they were covered in 150 year old newsprint. I tore open the wrapper as fast as I could and then I stopped – just froze. After staring at my hamburger for a second, I looked up at her with a look of bewilderment on my face and exclaimed, “That’s not what it looks like in the commercial!?!” Life lesson learned.

But there’s good reason why that hamburger in my hand didn’t look as good as the one on TV. There’s no way it could have. Take a look:

Keep this video in mind the next time you find yourself drooling over the cover of a cooking magazine while standing in the checkout line. There’s probably nothing in that photo you could actually eat if you got your hands on it.

Remember it the next time you feel a sense of inadequacy glancing at the cover of a fashion or health magazine, too. The models and celebrities who make those covers are exceptionally beautiful people – that’s why they’re on the cover; but not even Selena Gomez or Idris Elba or Gigi Hadid or Hugh Jackman look that good in real life. They’ve been fictionalised with lights and filters and airbrushes and other editing techniques just like a certain hamburger.

This is the society in which we live: a culture of illusions if not fabrications and outright falsehoods. We cannot fully trust our eyes whenever we are looking at a screen (which is quite a bit of the time these days), and that is simultaneously amazing and unsettling. Amazing because what we can engineer is simply incredible. Unsettling because the line between what’s real and what’s digital is growing thinner by the year. I watched the first Pirates of the Carribean movie (2003) with my girls recently, and I was shocked at how crude the special effects seemed by 2019 standards – because I could tell what was CGI and what wasn’t.

And not being able to tell is fine when we’re at the movies or watching TV, seeking by choice to be entertained, willingly suspending our belief to be immersed in a world of make believe. The trouble now is we don’t always have the choice. That special effects technology used to create the latest summer blockbuster is not confined to the movies or even to production studios. Simplified versions are available to pretty much anyone who can afford a laptop and the right software.

One of the more problematic developments of the last few years is the advent of the “deepfake.” Deepfake technology uses the same motion capture techniques used by Hollywood special effects artists to digitally transpose a person’s face onto another person’s body, or one person’s mouth onto another person’s face. The software then enables the creator to more or less seamlessly merge the images to make it appear that the person (usually a celebrity) is doing or saying whatever the creator desires. In the context of cinema, this technology opens up wide new horizons for creativity. On the political stage or in the social arena, however, it holds the potential for tremendous harm. Already videos showing politicians saying things they never actually said are circulating online. Thankfully, at the moment, many of these homemade deepfakes can be spotted fairly easily. But the day is fast approaching when distinguishing fact from fiction will require careful examination as the technology advances and deepfakers gain more experience.

[ WARNING: Langage Advisory ]

Yet, even now, knowing that pretty much anything we see could have been manipulated or altered in some way leaves us feeling unsettled and un-moored. We’re not always sure what we can trust – especially online. And that mistrust may very well be spilling off the screen and off the page into other areas of life. I can’t help but wonder if there’s a correlation between the sophisticated evolution of our digital existence and the reactionary devolution of our politics. Put another way, as our society has become both increasingly visual and more skeptical about what we see, are we more suspicious of each other as a result?

Of course, we’re not the first generations to have to deal with artifice and deceit. There’s nothing new under the sun (Ecclesiastes 1:9). The difference for us is the scope and scale of the present challenge. Previous generations have not lived in an age where the appearance of reality can be manipulated with such ease and that manipulation can be distributed en masse with even greater ease, thanks to the internet.

This reality gives particularly urgency to Walter Brueggemann’s assertion that “telling the truth in a society that lives in illusion” is one of the prophetic tasks given to the church. Our world is in desperate need of truth-telling.

“telling the truth in a society that lives in illusion” is one of the prophetic tasks given to the church.

Before we can tell the truth, however, we have to seek the truth and be committed to the truth – even at personal expense. As Baptist disciples of Jesus, Scripture is where we turn first whenever we seek truth. There is a lot about truth contained in the Bible. But truth-telling as a prophetic task involves more than declaring that Jesus is “the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6); more than quoting any series of verses. I’m going to suggest that two of the most important scriptural anchor points for truth-telling actually don’t have anything overtly to do with truth.

The first is the Apostle Paul’s exhortation in 1 Thessalonians 5: test everything. The NIV’s rendering, “Do not treat prophecies with contempt, but test them all,” is far too limited in its focus. πάντα δὲ δοκιμάζετε means to test, probe, even taste all things. We need to test proclamations, interpretations; the directions and instructions given by our leaders; the convictions and motivations our own hearts and minds. My wife used to have a bumper sticker on her car that read, “Don’t believe everything you think.” And it’s true. Rene Descartes helped launch the modern age by stating, “I think therefore I am.” In our postmodern, post-fact age this idea has metastasized into “I think therefore I am right.” Truth is all of us are prone to accept false or misleading information based on our preconceptions and predilections. The waters of baptism don’t wash away our personal biases. We Christians might be more susceptible, in fact, to accepting without pause or critique assertions that reinforce what we already believe precisely because faith (conviction) plays such a significant role in our lives. And it’s oh so easy to hit that “share” button online. It’s oh so easy to pass conjecture and rumour down the pew when we’re at church. So we have to test everything – in relation to the larger culture and within our church fellowship.

We also have to make sure we pursue truth-telling in ways that are faithful to the gospel. Truth-telling can be painful and even harmful. It can be done in the wrong way, even done for the wrong reasons. Blackmail is a twisted form of truth-telling, after all. It’s using the threat of revealing the truth as a means of leverage or personal profit.

We should note that Paul’s instruction to “test everything” is not given in isolation. It’s one of many encouragements offered in this closing section of 1 Thessalonians 5. It’s an instruction that’s very much anchored and delivered in the context of a beloved community: of a church that as a family “encourages one another and seeks to build each other up” (verse 11). The church at Thessalonika has shown itself to be a community that prays and rejoices together, a place where people assist each other and are patient with one another; a fellowship where people want the best for each other, where they see every member of the body as loved, forgiven, and worthy of Christ’s redemption. There’s a difference between diligence and suspicion.

“Paul and Brueggemann are both speaking of truth telling as an exercise in liberation, not accusation.”

Paul and Brueggemann are both speaking of truth telling as an exercise in liberation, not accusation – and certainly not as an act of arrogance or self-righteousness: See – I’m right, you’re wrong. And this is where Jesus’ words from the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5 come in. You are the salt of the earth. You are the light of the world. Let your light shine. Faithful truth-telling shines a light of hope, it never casts a shadow of condemnation.

When I read Jesus words in Matthew 5, my mind also then leads me to Ephesians 5, where Paul elaborates on Jesus’ theme of living as bearers of light. For once you were darkness, but now in the Lord you are light. [Therefore] live as children of light (verse 8). Yes, part of living as children of light involves exposing the works of darkness (telling the truth); but the motivation here is not to exult or gloat over the darkness. Rather, it is to see the darkness transformed. For everything exposed by the light becomes visible, for everything that becomes visible is light. Think about that for a moment. Everything that becomes visible is light! It’s an extraordinary claim – but one consistent with the life-giving, love-transforming gospel. There is a light that shines in the darkness and the darkness does not overcome it (John 1), because the light Jesus brings, the light Jesus gives, converts the darkness into light. That’s what Jesus seeks. It’s what faithful truth-telling seeks, too.

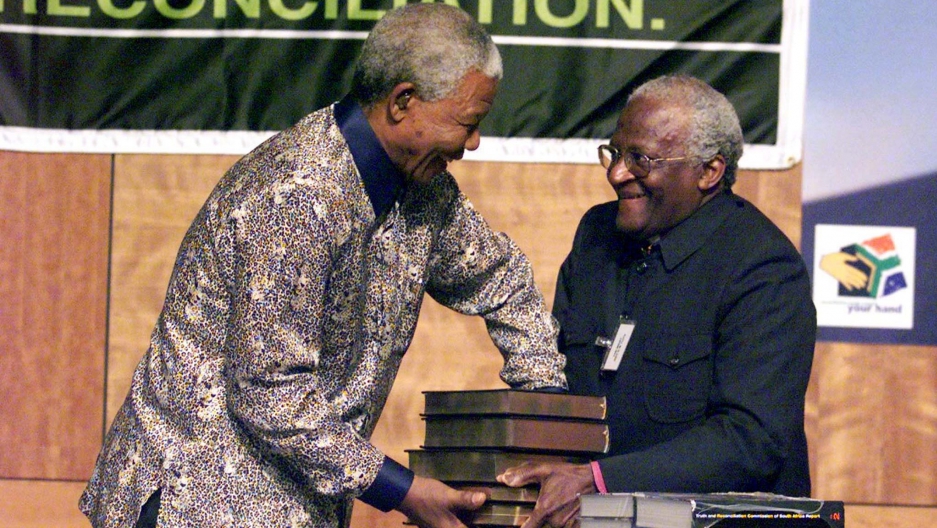

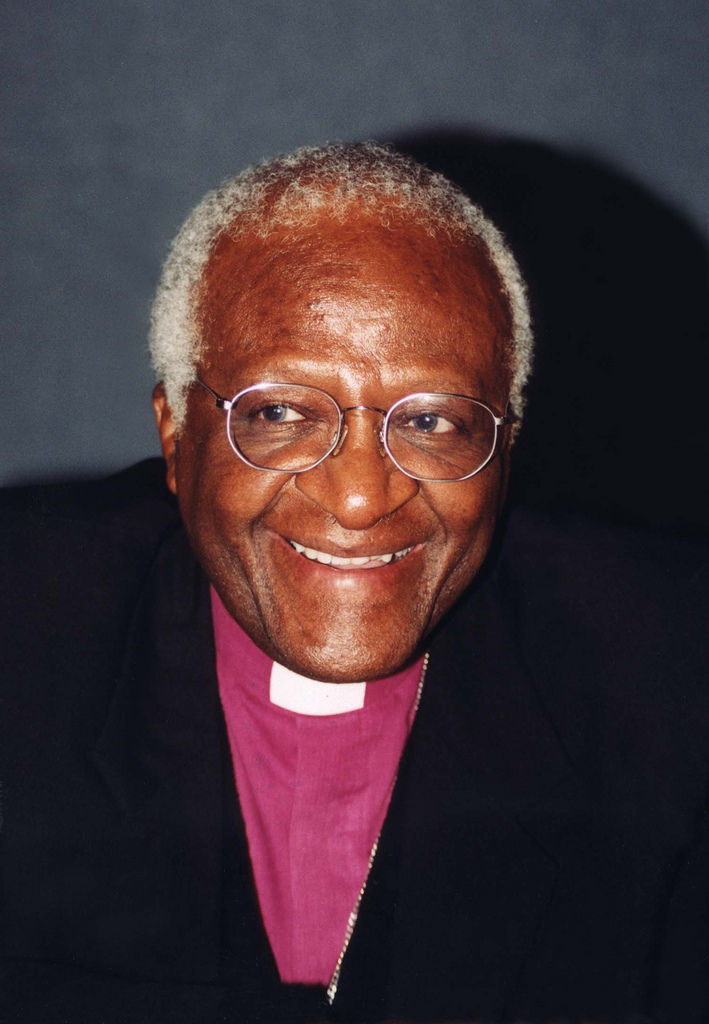

In recent history I can think of no better example of faithful, life-giving, light-bearing truth-telling than the work of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission – instigated by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and other faithful leaders possessing great prophetic and pastoral qualities. The commission shepherded the exposure of the works of darkness in apartheid South Africa. But the goal of this exposure, the aim of this truth-telling in a national ( international) forum was never revenge or retribution. It was always forgiveness and absolution. It was confession in exchange for grace – which is what the Christian concept of confession is all about. And this choice – the choice to go after truth in this grace-filled way – served to set the fractures of a pummeled and concussed nation so that healing might begin.

South Africa’s commission served as the model for Canada’s own truth and reconciliation process in the 21st century as we seek confession and healing in our relationship with First Nations people on this soil – and well it should. But it should do more than that for those of us gathered in church on Sundays. It should serve as a model for our church and every church for how to conduct our life together when our pilgrimage becomes difficult. The only difference should be that, in the church, this work shouldn’t be the purview of a special commission; it should be the work, the task, the ongoing practice of all of us: truth-telling for the sake of transformation and absolution.

Not only is that what Christ calls us to; it’s what the world needs from us. Especially in this age of ubiquitous illusion, people are longing for something genuine and substantive to plant their feet on. And isn’t that what we have to offer? The good news of the gospel, the story of Christ who is the Rock beneath our feet, the creator and liberator all creation. As Jesus Himself declared, if you build your house on this rock, it will not be moved, not matter how unpredictable the swirling sands of life become (Matthew 7:24-27). That’s what we have been given; that’s what we have to offer. The question is, “Is that what people find when they show up? Is that what people see when they observe and experience our life together?”

May it be so, for the health of our congregation and the vitality of our witness to the world. Amen.