This is the fifth in a series of articles examining the parallels between the history of the Baptist church in America and the history of Old-Time String Band Music. Why it matters, here.

In 1928, seven years before Old Time music aficionados first gathered in Galax, Virginia, a fiddler’s convention for black musicians was held two hours away in Martinsville, Virginia. The Black Fiddler’s Convention continued into the 1940s and the fifty-cent admission paid by black and white attendees provided small prizes for the winning acts (Spalding, 70-71). But the tradition of black string bands is virtually unknown by those sitting in the bleachers in Felt’s Park during the Old Fiddler’s Convention in Galax. In fact, when the African American old time music group, the “Carolina Chocolate Drops”, first began to make a name for themselves, member Rhiannon Giddens says they were warned not to go to the predominantly white Galax convention[1](Giddens, 14). Not until 2010, when 13-year-old African American musician Travis Starkey placed fourth in the guitar division, would a black guitarist win a prize in Galax (Dickens).

This is scandalously late in the convention’s 85 year history, but perhaps, sadly, not unexpected given the history of racism in Grayson County. “A process of healing, decolonizing, and reclaiming is necessary in order for us to move forward,” suggests African American bones musician, Kafari in a collaborative Ted talk with white banjoist Jake Hoffman (TEDDirigo, below). While Kafari is speaking specifically about old time music, he is not speaking exclusively about music. His prescription for healing could be applied culturally and I would argue that a similar process of healing is also needed in the Baptist church. In another engaging TED talk, Dom Flemmons of the “Carolina Chocolate Drops” introduces the concept of “sankofa.” A proverb from the Akan tribe in Ghana, “sankofa” means to “go back and fetch” that which is in danger of being left behind with the knowledge that the wisdom of the past brought into the present can enlighten the future (TEDUNC, below)[2].

“We must go back before we can go forward,” is also CCDA founder John Perkins’ admonition to churches who want to make a difference in racial reconciliation (Kwon). Any effective Truth and Reconciliation process must first dig deep and discover the ugly truth about the past and its effects on the present. Some Baptist organizations have made formal statements like the SBC’s 1995 Racial Reconciliation Resolution, that, while 150 years overdue, is better late than never, but lacked the specifics that might have motivated the convention to make amends. Southern Seminary’s investigation into its pro-slavery past was conducted by a committee of faculty members and while it skims over slavery as the SBC’s founding issue (citing “efficiency” and “honor”) the report does provide detailed quotes from pro-slavery presidents, preachers and professors. Their racist words, slave ownership, and support of the Klan is truly reprehensible, and it’s a nauseating and disheartening experience to read this report, especially as a Baptist, no matter your Baptist persuasion[3]. It is however necessary. Uncovering the truth gives those who seek to bring about change, a clearer picture of the problem, in the same way an x-ray or scan provides a physician the information she needs to repair a break or remove a cancer.

“Uncovering the truth gives those who seek to bring about change, a clearer picture of the problem, in the same way an x-ray or scan provides a physician the information she needs to repair a break or remove a cancer.”

But as with any serious medical diagnosis there’s always a grieving period[4]. As someone who has a special place in her heart for the Galax Old Fiddler’s Convention, I struggle with the realization that an event and a music that I love, and that provides such a conduit to some of my favorite childhood memories, has connections to racism and white supremacy. Banjoist Jake Hoffman agrees. “Learning a greater history of the banjo has been depressing, humiliating, and thinking about how I fit into this modern world as a banjoist is uncomfortable because it makes me think of all the ways I’ve condoned the erasure of black history and black art,” he confesses in a recent TED talk. Hoffman’s acknowledgement, however difficult, is the beginning of a necessary process that may ultimately lead to healing.

Perkins refers to this grieving process as the “lament,” and for him, the lament “must acknowledge that something horrific has happened,” and this is where the Southern Baptist response falters (Kwon). The facts are there, but the 71-page report lacks feeling. It is clinical rather than remorseful, and fails to adequately address the ripple effects of the school’s past support of slavery and racism and how it impacts the present. The “Report on Slavery and Racism” also lacks any recommendations for reparations or any call to action. The Louisville church coalition, EmpowerWest, called on Southern to give part of its 95 million dollar endowment to Simmons College, a historic black college founded in 1879 by former slaves. President Al Mohler’s response was an emphatic “no” citing “theological differences”. “Ironic”, says alumnus and EmpowerWest co-chair, Rev. Joe Phelps, considering it was a point of twisted theological interpretation that Southern Seminary’s founders used to excuse their ownership of slaves in the first place (Kobin). With Alumni and SBC congregants calling the report a “waste” of time and money, it’s doubtful Southern Seminary will take any steps to atone for its past (Ross).

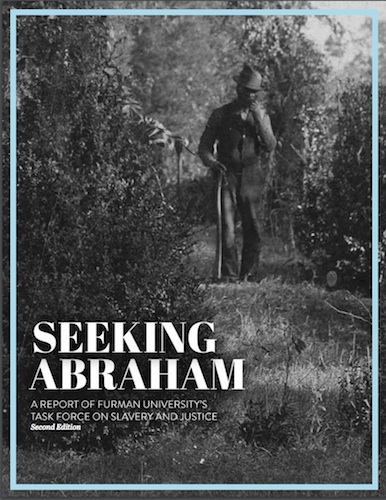

Elsewhere in the south, another university with a history of slavery undertook a similar investigation yet with a much different process and outcome. Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina was named for the first president of the Baptist Triennial Convention, Richard Furman, whose Biblical justification for slavery provided Baptists in the south the excuse they needed to continue the enslavement of black human beings in America. In a fitting reversal, Furman University’s self-examination of its past may set the standard for other institutions to name, lament, and make amends for their racist past in the spirit of sankofa.

Slaves literally built the original Furman University campus in South Carolina, and profits from slave labor funded the school for decades. Racist attitudes prevailed even longer. Almost two centuries after Furman published his “Exposition of the Views of Baptists Relative to the Colored Population…”, an article published in the campus student newspaper prompted Furman the university to undertake an investigation into the school’s slave holding past. That the group of alumni, professors, students, and archivists who came together to do the work was called the “Task Force on Slavery and Justice,” signaled a positive beginning. The task force met with specialists and with black community leaders. These experiences influenced their decision to adopt the more substantial word “reckoning” to describe their undertaking over the oft used “reconciliation” because it communicated an “accounting for intergenerational injustices.”

The task force’s work, along with seminars and lectures from guest speakers, including Baptist historian Bill Leonard, compelled the university to make changes to the school’s physical campus, finances, and educational practices. Furman renamed campus streets and halls, installed new historical plaques and statues, and added additional context to old ones. The Office of Financial Aid expanded scholarships to students of color, and all financial investments must now meet certain standards to ensure the absence of modern slavery in their practices and supply chains. Furman has made educating its students about the school’s past a priority and, in addition to funding research, is also conducting alternative spring break excursions focused on gathering oral histories and cleaning up historical sites.

But the most impressive actions to come from Furman University’s self-examination are those directed toward doing justice in the community. The final report confesses that the current Furman campus location, in a suburb of Greenville was chosen to intentionally avoid the city’s growing African American population. It was not enough then, concluded the task force, to simply send students out in to the community “to do good”(the school’s motto). Instead, the university had a long overdue obligation to bring the community into the college. With that in mind, they proposed a summer program for African American high school students, partnerships with non-white professionals and artists, and a change to the university’s motto and mission that would reflect this new inclusive focus (Furman, 39-45). While none of these steps will erase the past, and some have yet to be implemented, they go farther than many other institutions. The university is poised to take a step beyond acknowledgement of the past by helping to reframe the future.

What would it look like if churches undertook such a process? There are a few antebellum churches, founded and funded by slavery, still standing on southern street corners. How many of these were damaged in the Civil War and rebuilt again on the backs of black labor? Reconstruction was not the end of slavery for African Americas, just a rebranding of it under the name “Jim Crow”. Throughout the twentieth century, the congregants of white churches benefitted from New Deal policies, and financial practices that favored them, income they then tithed this to their churches. Redlining not only prevented black Americans from building homes in certain areas, but also establishing churches and businesses in those areas (Miller). White churches enacted their own form of redlining when, like Furman University, they left downtown areas for the suburbs. This white flight, took with it resources, commerce and engagement that could have made a difference in the communities they left behind.

“If we as churches are willing to really engage in sankofa, willing to go back into the dark history of the Baptist church and learn from it, repent from it, carry that chastened wisdom into the present and let it guide our work, then even that darkness of the past, can become a light to the future.”

A modern day griot, a descendant of that hereditary class of African storytellers who brought the banjo with them to America, visited Duke University. He “emphasized that they [the griots] think of themselves as peacemakers, as people who can negotiate between different social groups or even amid political conflicts inasmuch as knowledge of the past can help people deal with the present” (Marks). If we as churches are willing to really engage in sankofa, willing to go back into the dark history of the Baptist church and learn from it, repent from it, carry that chastened wisdom into the present and let it guide our work, then even that darkness of the past, can become a light to the future. Then churches might be the peacemakers and bridge builders that Christ has called us to be. Baptists have much to lament and repent, but we also have the promise of a Strength greater than ourselves to guide and equip us in the work of reconciliation. As God continues God’s work of reconciling the world through Christ, it is never too late for us to begin the work entrusted to us to reconcile with one another.

Bibliography

Blue Ridge Music Makers Guild, Music Makers of the Blue Ridge Plateau. Arcadia, 2008.

Conway, Cecelia. African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia: A Study of Folk Traditions. U of Tennessee Press, 1995.

Dickens, Tad. “Old Fiddler’s Convention Results Include a First for a Young African-American Guitarist,” Roanoke Times August 16,2010.

Emmick, Matthew S. Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music Butler University, 1995.

Epstein, Dena J. Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War. U of Illinois Press, 2003.

Giddens, Rhiannon, “Community and Connection,” IBGM Keynote Speech, 2017.

Gourley, Bruce. John Leland: Evolving Views on Slavery 1789-1839. “Baptist History and Heritage Journal.

Gura, Philip and James F. Bollman. America’s Instrument: The Banjo in the Nineteenth Century. UNC Press, 1999.

Kafari, and Jake Hoffman. “Bones and Banjo: Confronting Cultural Appropriation,” TEDDirigo, December 20, 1917.

Kobin, Billy. “Louisville’s Southern Baptist seminary rejects call to make slavery reparations”

Kwon, Duke. “ John Perkins Has Hope for Racial Reconciliation. Do We?” Christianity Today April 5, 2018.

Leonard, Bill. “Baptists and the Bible, Slavery and the Lost Cause: Inseparable Hermeneutics of Racism,” Furman University, April 2018

Linn, Karen. That Half- Barbaric Twang: The Banjo in American Popular Culture. UI Press, 1994.

Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class . Oxford UP, 2013.

McTyeire, H.N., C.F. Sturgis, and A.T. Holmes. Masters to Servants: Three Premium Essays. Southern Baptist Publication Society, Charleston, S.C., 1851.

Miller, Johnny. “Roads to Nowhere: How Infrastructure Built on American Inequality,” The Guardian February 21, 2018.

Reiner, David. Old Time Fiddling Across America. Mel Bay Publications, Fenton, 2015.

Ross, Janelle. “Southern Baptist report on slavery ties includes no reflection on racial equality today.” NBC News Dec.16, 2018

Sankofa, Reclaiming History. The Carolina Chocolate Drops at TEDxUNC. March 5, 2013.

Spalding, Susan Eike. Appalachian Dance: Creativity and Continuity in Six Communities. U of Illinois Press, 2014.

Worsham, Gibson. A Survey of Historic Architecture in Grayson County, Virginia including the towns of Independence and Fries. Conducted for Virginia Department of Historic Resources Richmond, Virginia. Winter 2001 – Spring 2002

[1] The group has since performed at the Blue Ridge Music Center in Galax.

[2] “Sankofa” literally translates “It is not wrong to go back for that which you have forgotten.” One symbol of sankofa is a bird with its head bent back over its wing looking backwards, and holding an egg in its mouth.

[3] Those of us who left the SBC for other denominations, are not exempt from the hard work of repentance and reconciliation. The same privilege built the churches that left as well as the churches that stayed.

[4] Not unlike the remorse that Jake Hoffman expressed, and that I myself have felt many times during the researching and writing of this series.

Feature image: Sankofa bird weight of Ghana made of brass. Courtesy of the British Museum.