This is the third in a series of articles examining the parallels between the history of the Baptist church in America and the history of Old-Time String Band Music. Why it matters, here.

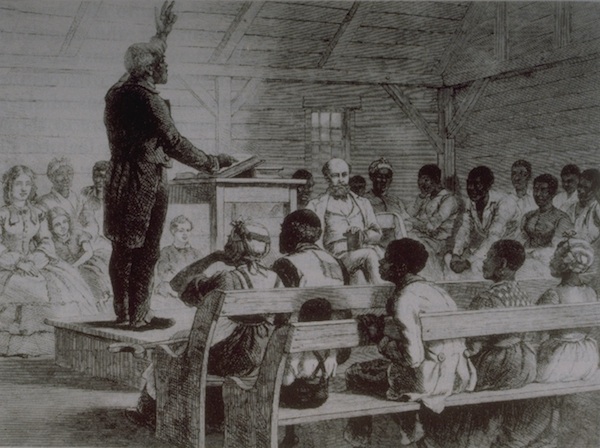

Proponents of slavery argued that if the Bible was wrong in permitting slavery, then maybe it was wrong about salvation, and since it had to be right about salvation, it must be right about permitting slavery and requiring slaves to obey their masters (Leonard, Furman Address, 3). The flip side of this argument was the call for masters to exercise a paternal benevolence toward their slaves. Just what this “benevolence” entailed is unclear, so to help slave owners, the Baptist Convention of Alabama sponsored an essay contest in 1849 with a $200 prize for the winning entry on the topic of “Duties of Christian Masters to their Servants.” The top three essays were printed and distributed. All three winners were ministers[1]. Baptists in the south sent missionaries to plantations to preach and congratulated themselves on providing enslaved Africans with the opportunity to hear the gospel. Ever the leader in denominational delusion, the Alabama convention actually purchased the slave Caesar McLemore to “preach and work among blacks” (Richards, 39).

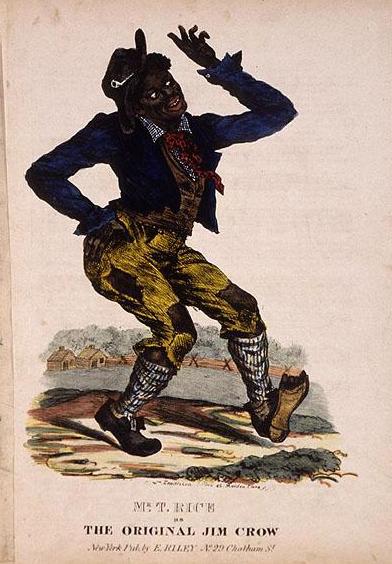

Simultaneously, the rising popularity of the minstrel show aided the mythology of a benevolent master considerably. Minstrelsy originated under the circus tent in the late 18th century. There, clowning performers would darken their faces with burnt cork and play the banjo or fiddle along with singing and dancing. In 1828 T.D. Rice painted his face black and performed a song and dance routine on a New York stage that mimicked southern slaves. A few years later, Joel Sweeney, who learned the banjo from slaves, took that instrument on the road and toured as the “Virginia Melodist,” with what he claimed were genuine slave songs of the Old Dominion. Later in 1843 a troupe of veteran blackface circus performers in New York City would combine their talents on banjo, fiddle, tambourine, and bones[2] to form the Virginia Minstrels (Gura, 20). Their songs and skits about the lives of slaves, performed in exaggerated “Negro dialect,” became the standard for minstrel shows to follow and ignited a craze for blackface in the US and Europe.

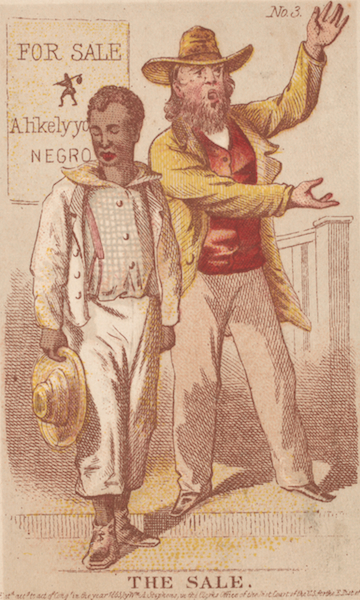

Minstrel shows featured a reoccurring cast of characters, amongst them the fat and faithful Mammy; Zip Coon, the indolent dandy; Jim Crow the slow, shuffling country cousin, and an assortment of neglected, disposable pickaninny children. For many northerners, the distorted caricature of the minstrel show was their first exposure to anything resembling black life in the south. With posters advertising “Negro” performers, many in the audience including Mark Twain’s mother, thought they were watching actual slaves performing, rather than white musicians in blackface (Lott, 20)[3]. Another staple of the minstrel show was the Sambo character, so innocent, childlike, and in need of white protection that he longed to return to his plantation home. The underlying message to white audiences was that a people who were that lazy, inept, and ignorant deserved or even needed to be enslaved for their own good as well as society’s. Minstrelsy depicted slavery as harmless. Even violence was played for laughs, and it desensitized people to the real horrors of chattel slavery (Kelley)[4].

This happy go lucky, carefree version of slavery fit well with the narrative of the benevolent master that Baptists in the south were pushing, and provided others who claimed neutrality a convenient cover. Giving to foreign missions was precariously low in 1840 due to disputes over slavery (Richards, 22). Georgia and Alabama Baptists refused to deliver their contributions until assurances were made that slaveholders would not be ”disfellowshipped” (Matthews, 17). So the Triennial Convention, in a last ditch effort to unify Baptists for mission work, made “agree to disagree” it’s official position on slavery. Slaveholders, and those beholden to them, sent their tainted tithes north, where the Foreign Mission Board proceeded to use the money made off the backs of enslaved Africans to fund missionaries to places in Africa[5].

“Slaveholders, and those beholden to them, sent their tainted tithes north, where the Foreign Mission Board proceeded to use the money made off the backs of enslaved Africans to fund missionaries to places in Africa”

The “don’t ask don’t tell” approach to the slavery question was couched in terms of making space for individual and church autonomy, but was the big tent of Baptist identity in actuality more a circus tent for hosting a Baptist minstrel show? At first glance the reasoning and motives appear sound. Church autonomy, the freedom to interpret scripture, and a passion for missions are all hallmarks of what it means to be Baptist. Disagreements on a variety of issues are expected. However, when the Baptist denomination tolerated slavery, the epitome of loss of freedom, it eroded its very foundation, and became an ugly caricature of it’s former self.

Baptists value the freedom of individuals to make religious decisions for themselves, but how free can a decision to follow Christ be, when it is made by someone who depends on the conduit of that Christian witness for food, shelter, and his or her very life? Slaves were required to have the permission of their masters to be baptized or to join a church, and once in those churches they did not have equal standing to preach, teach, or reprimand white members. Independent black churches with free and enslaved members, if they were allowed to exist at all, were assigned white ministers, in contradiction to established Baptist practice. The freedom to interpret scripture for oneself was replaced with a pro-slavery reading of the Bible in southern churches. When Rev. Knapp in Richmond, Virginia attempted to preach on the text of “loving one’s neighbor as oneself,” and included blacks among those neighbors, he had to flee the state in fear for his life (Matthews, 11).

In the south 15,000 Baptists were slaveholders, but 100,000 Baptists were enslaved with no voice or representation in state or national associations in a denomination that prided itself on its democratic ideals. In the Free states lived 324,660 Baptists but the abolitionists among them could do little to persuade their southern brethren. Non-slave owning Baptists in the southern states numbered 403,000 but their views on slavery were greatly influenced by those slave owning few who held positions of influence in the state associations and state Baptist papers. Anti-slavery Baptists were slandered in the Baptist press, excluded from state leadership and even publicly prayed against (Matthews, 20).

But could things have been different if Baptists in Free states, had called to abolish slavery rather than appease slaveholders? Had a fraction of the 403,000 non-slave owning Baptists in the south been persuaded to retain their original anti-slavery stance by a decisive call to resistance in the name of Christ, could they have ended slavery decades earlier?

Bibliography

Gura, Philip and James F. Bollman. America’s Instrument: The Banjo in the Nineteenth Century. UNC Press, 1999

Kelley, Blair L.M. “A Brief History of Blackface,” The Grio. October 30, 2013.

Leonard, Bill. “Baptists and the Bible, Slavery and the Lost Cause: Inseparable Hermeneutics of Racism” Furman University—April 2018

Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class Oxford UP, 2013.

Matthews, Edward. The Shame and Glory of American Baptists: Or, Salveholders Versus Abolitionists, Thomas Matthews, Broad-Quay, Bristol, 1860. Richards, Rogers Charles. Actions and Attitudes of Southern Baptists Towards Blacks: 1845-1895. Florida State University Libraries, 2008.

[1] Winner H.N. McTyeire went on to co-found Vanderbilt University.

[2] Bones were actual rib bones or other animal bones held by the performer and shaken to produce a castanet sound. Don Flemmons of the Carolina Chocolate Drops performing on the bones.

[3] Twain and his mother saw Christy’s Minstrels. Christian families who shunned the theatre made an exception for this troupe, which was “well patronized by good people.” (31).

[4] After the Civil War, slavery may have ended, but minstrelsy did not. Only, in the Jim Crow era, African Americans began to take the stage as professional performers. Though still required to wear black face, vaudevillians like Bert Williams paved the way for black musicians to later perform on their own terms. The banjo went on to become a featured instrument in ragtime and jazz orchestras

[5] 1814-1832 missionaries were sent primarily to Africa and Burma. White missionaries were thought more susceptible to diseases in Africa and were replaced with black missionaries.