In my humble estimation, the story of Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch in Acts chapter 8 is one of the most overlooked stories in the New Testament. It’s not unknown; it’s simply not probed with care. I suspect one reason for that is because of where the story falls in the Book of Acts. Too often, we’re in a hurry to get on to the much more famous story found in Acts chapter 9. That’s where we read about Saul of Tarsus’ conversion on the Damascus Road. It doesn’t get bigger than that outside of Christmas and Easter.

But I would submit that we cannot fully comprehend what happens on the Damascus Road without fully comprehending what transpires on this much more remote and less frequented road between Jerusalem and Gaza. In fact, I would go further and suggest that we cannot fully understand the gospel writ large without fully confronting Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch. I think we’d all agree the gospel is about radical grace. It has to be radical for it to be amazing. If it’s qualified or tempered, it’s not amazing; it’s rather ordinary and certainly not much to sing about. So, if the grace of the gospel is radical so too must be the reach of the grace, and that is the point Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch drives home.

“if the grace of the gospel is radical so too must be the reach of the grace, and that is the point Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch drives home.”

On the surface, this story seems straightforward enough. The Holy Spirit tells Philip to go on a journey, heading south from Samaria, which is where we find Philip at the beginning of Acts 8. As Philip is going along the road, a court official from Ethiopia happens by in a chariot. He’s reading Scripture as he rides, and he has questions about what he is reading. Jesus’ man Philip has the answers to those questions. He shares the gospel with the official, the official sees the light, Philip baptizes him, and then (his work here done) Philip continues on his merry way to continue proclaiming the “good news.”

That’s a rather glib summary of Luke’s account, but it’s not far off from how Philip’s encounter with the Ethiopian eunuch is often presented – and exactly how it CAN be presented read if we read in too much of a hurry, merely skimming the surface without plumbing the depths.

But when we slow down; when we, like Philip, take the time to sit in and ride along with this chariot; when we take the time to immerse ourselves in the details and understand where we are and with whom we are, we find the of the Ethiopian eunuch resists such a simple, benign, reading. This is a transformational, not just a transitional, story. So let’s dive into the details.

First, we’re walking with Philip down a “wilderness road.” This is no flippant or casual detail, even though you’ll probably find it inside parentheses in your English translation. It’s a detail to clue us in as to the significance of this place. Philip is off the beaten path, in unfrequented if not uncharted territory.

Wilderness is by definition unfamiliar ground; but wilderness is also the place where God both frees and forms God’s people. It’s where God’s people have to roam in order to find their way to the Promised Land. Anytime we encounter wilderness in Scripture, God is up to something. Something new. When we encounter wilderness, we have to ask ourselves: What are we moving toward? AND What are we being freed from?

“When we encounter wilderness, we have to ask ourselves: What are we moving toward? AND What are we being freed from?”

Second, the official whom Philip meets on this wilderness road is a eunuch. You might read in a footnote in your Bible or in a commentary that a eunuch can simply mean “a court official.” It can simply be a title. And that’s true. It can. But reducing the term “eunuch” to such a definition is akin to reducing the theme of Romeo and Juliet to young love. It omits unpleasant and uncomfortable details – and social and political implications – we’d rather not bother with.

So, we need to be honest about who and what a eunuch is. Eunuchs were castrated male officials, who were often enslaved.

Some eunuchs were “born that way,” suffering some sort of genital birth defect (Matthew 19:12); but most were “made by human hands,” typically without consent of the eunuch.

In Greek, the word literally means “bed guardian” and eunuchs were employed in Near Eastern royalty households to protect the women’s quarters, the harem of the king. We read about one such eunuch in the book of Esther (2:3,14). Eunuchs might also serve a particular religious function in a temple or be created to preserve their prepubescent features for singing or other ritual purposes. As a result, eunuchs tended to live and move in the upper echelons of society and they could rise to high positions of trust, responsibility and influence within circles of power. Such is the case with the eunuch in we meet in Acts 8, whom we are told is in charge of his queen’s treasury.

And yet, eunuchs were disdained and ridiculed even as they were prized. Because their bodies lacked the normal male hormone balance, their appearance was often rather odd —especially if they had been castrated before entering puberty. In ancient literature eunuchs are often described as having disproportionately long limbs, yellow-ish, flabby skin, little if any facial hair, and boyish voices. So, interacting with a eunuch was a strange and even disconcerting experience. Imagine Jordan Gray’s voice coming out of Mike Gray’s mouth and you’ll get something of the idea.

Among the Hebrew people, eunuchs were scripturally stigmatized in addition to being socially stigmatized. The prohibitions of Deuteronomy 23.1 and Leviticus 21.17-21 bar eunuchs from the altar and even from the assembly of the Lord.

All of this is what the word “eunuch” would have conjured for Luke’s first readers, and the word needs to be similarly freighted for us as we envision Philip’s encounter on this wilderness road somewhere southwest of Jerusalem. If we try to sanitize it or downplay it, we’re going to miss the significance of what is about to happen.

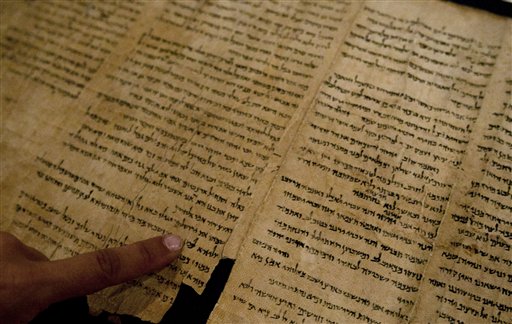

We also need to grasp the significance of the word “Ethiopian.” This isn’t the third world country most of us know from the news. The Greek poet Homer describes it as an exotic land of wealth and mystery, on the edge of the world, a place where the gods would regularly visit for a little R&R. In the Old Testament, it was known as the land of Kush, which the prophet Isaiah names as one of the four corners of the earth from which God will draw the faithful remnant of God’s people (11:11). To the Romans, it was known as the Kingdom of Meroe, a land Rome never conquered. In fact, one of the best-preserved images of the Emperor Augustus from antiquity is the bronze head of a statue that was captured by Kushite troops from a southern Egyptian town. It was discovered in 1910 intentionally buried beneath the steps of a Kushite temple so that the people of Meroe would literally walk over the emperor’s face as they came and went from worship.

So for Luke’s original audience, this eunuch would have represented the ultimate outsider. He is “the other” in every sense – culturally, sexually, politically, geographically – someone who doesn’t fit neatly into any familiar category.

And yet, this eunuch is very much seeking God. He’s returning from a pilgrimage in Jerusalem that he would not have been permitted to participate in except in the most superficial of ways. On the long journey home, he’s reading the prophet Isaiah: a passage from the section usually referred to as “The Suffering Servant,” no doubt a section that would have resonated with the eunuch in particular ways given his on earthly experience. It’s truly remarkable.

Equally remarkable is that the Holy Spirit urges Philip to engage this eunuch in anything but a superficial way. Philip is instructed to go over and “join” the chariot. The Greek denotes close proximity. It can even mean, “to stick to like glue.” Philip is crossing a boundary here. This is a close and personal encounter with someone normally held at arm’s length.

Philip overhears what he is reading (which, by the way, would not have struck Luke’s readers as odd. In the first century people typically read out loud, even to themselves) and so Philip asks if he understands: a question that, in the Greek Luke employs, implies comprehension through experience not just through the intellect.

This is a passage that no doubt would have resonated with Philip as well: The “Suffering Servant” isn’t often quoted directly in the NT, but it was a section of Isaiah that was interpreted by the early church as referring to Jesus.

The eunuch replies: how can I unless I have someone to guide me – a question that arises from the life experience of someone who, despite his material comfort, is always being directed. From someone enslaved by other human beings, estranged from other human beings and also told that he is estranged from God.

Notice, then, what happens next: Philip gets in the chariot and rides with the eunuch. Up close and personal

The eunuch wants to know who the prophet is speaking about: himself or someone else? I hear a lot of empathy in the eunuch’s question – one suffering individual interested in another suffering individual.

Then Philip does what we see the apostles and the other ordained disciples do throughout the Book of Acts – he imitates Jesus. Starting with this scripture, Philip proclaims the good news about Jesus on this wilderness road – just as Jesus Himself began with Moses and the prophets and interpreted all the things about Himself in the scriptures for the disciples on another road, the Road to Emmaus.

After hearing Philip out, the eunuch’s response is also somewhat Christ-like. He asks another question: “Look, here is water. What prevents me from being baptized?” Note the particular phrasing. He wants to be baptized but anticipates there could very well have been an objection. And in the minds of at least some of Luke’s original readers, the answer would have been everything! How could such a quintessential outsider, banned from the assembly of the Lord according to Mosaic Law, be baptized just like that without any further consideration?

Whatever words Philip might have said in response, Luke does not share. In the narrative Philip answers with action. And I would suggest what Philip DOESN’T do is as important as what Philip DOES do.

“The Holy Spirit led him to this place, to this person. The Holy Spirit led him to come alongside this eunuch. So Philip gets down in the water with the eunuch just as he had gotten up into the chariot with him.”

Does Philip run and ask Peter or John what he should do? No. Does he form a committee to study the question and report back to the eunuch at a later date? No. The Holy Spirit led him to this place, to this person. The Holy Spirit led him to come alongside this eunuch. So Philip gets down in the water with the eunuch just as he had gotten up into the chariot with him. And from what we know about early baptism, this would have involved both Philip and the eunuch leaving their clothes at the water’s edge. Which means Philip’s encounter with this quintessential outsider becomes about as personal and unconstrained as possible. All outer forms of pretense are removed for this baptism to occur (as they should be for any baptism to occur!) and the disciple and the eunuch stand naked before God and before each other.

This is precisely Luke’s point: in Christ, the Law is fulfilled. Jesus is now the focus. Jesus is now the end all and be all. The old boundaries between Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria, and the ends of the earth; the boundaries between Jew and Greek, male and female, slave and free are no more.

That is the church’s promised land. That is our destination. Our desire to cling to those old boundaries and classifications is the wilderness through which we must travel as we learn to blur and subvert those boundaries.

Our calling to take the gospel to the ends of the earth isn’t a theoretical journey, not one in which different classes or groups of people, like Samaritans or eunuchs, can remain abstract or distant. It’s one in which we must become willing to be fully immersed with people from all walks of life, especially individuals from stigmatized and marginalized groups, because that’s how we undermine and transform stigmatization and marginalization. And that involves an Easter wilderness journey for us to learn to walk with, ride with, converse with, and be vulnerable to those not like us, including the most quintessential outsiders. This journey to the ends of the earth is just that: a journey; it’s not a cruise.

Remember where we’re going? The Damascus Road. The conversion of the greatest of all the apostles, of the single most influential voice within the Christian faith next to Christ Himself. But don’t forget where and how Paul’s relationship to Jesus and the church began. Not as an eager missionary but as the man who held the cloaks of those who stoned the disciple Stephen in the street. The man who actively sought the church’s destruction.

And beyond the Damascus Road we’re going to the home of Cornelius, the Roman centurion, upon whose household God will pour out the Holy Spirit in equal measure to the way in which it was poured out upon the original disciples on the day of Pentecost. An event that will prompt the Apostle Peter to eat food he previously deemed unclean with people he previously deemed unclean and to declare, when all is said and done, “Can anyone withhold the water for baptizing these people who have received the Holy Spirit just as we have?”

The church, called by Jesus and driven by the Holy Spirit, is entering a new frontier, a new world defined by a different understanding of the relationship between God and humanity, a world defined by radical grace and radical reach. The Holy Spirit isn’t re-writing the Law; but the Holy Spirit, as the agent of the risen Christ, is most certainly opening the minds of the disciples to new understandings of that Law now that Jesus has fulfilled that Law. The Risen Christ now stands as the church’s lens for interpretation

The lingering question for us is: Are we committed to continuing this journey? Or are we content to staying where we are, where we’ve been, where things are comfortable and make sense, where we can rely upon, fall back upon our conventional understandings?

The Promised Land, the new reality of Easter, is marvelous to behold. Like Philip, it will leave us and the formerly stigmatized and marginalized filled with joy. But we don’t get there, we can’t get there, without going through the wilderness first. And part of our journey through the wilderness with the Holy Spirit is learning what it means to “join with” the other, to gain the faith, the courage, and openness to ride with them in their chariots rather than expecting them to hop into ours.