As our minivan wound its way through the Smokey Mountains to Sevier County, Tennessee, home of Dollywood Splash Country, I paused the latest Percy Jackson audiobook, to narrate a story of my own for my captive (if not captivated) audience. Namely, “The Life and Times of W.C. Chandler,” a thrilling and inspiring tale about their great-great-great-great grandfather William Caswell Chandler, who, like Dolly Parton, grew up poor in the mountains of Sevier County. When he was fourteen years old the Civil War was raging and W.C. ran away from home to enlist in the Union Army.[1] His regiment didn’t get far before they were captured on their way to Virginia and imprisoned in Richmond’s infamous Libby Prison.

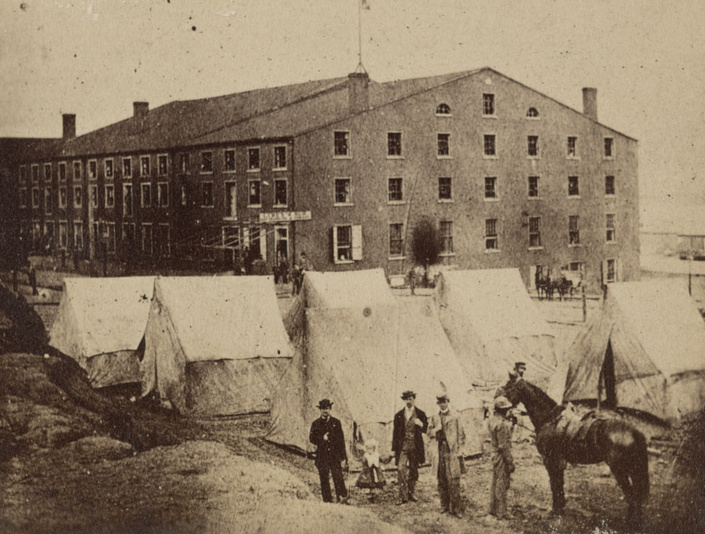

Libby Prison’s reputation was second only to the notorious Andersonville prison in Georgia when it came to death, disease, and malnutrition. During rainy weather, flooding in the basement would send rats stampeding through the cell blocks thus earning the prison the nickname “Rat Hell” (Talkov). With over a thousand prisoners crowded into the former warehouse, Grandpa Chandler was fortunate to have survived his time there. On a visit to Richmond in April of 1865, Abraham Lincoln toured the vicinity around Libby Prison. His advisors sought to have it torn down, but Lincoln suggested the building should remain standing as a monument to the Union soldiers who had suffered and died there in service to their country (Porter, 299). No one in Richmond that day could have predicted what would happen next.

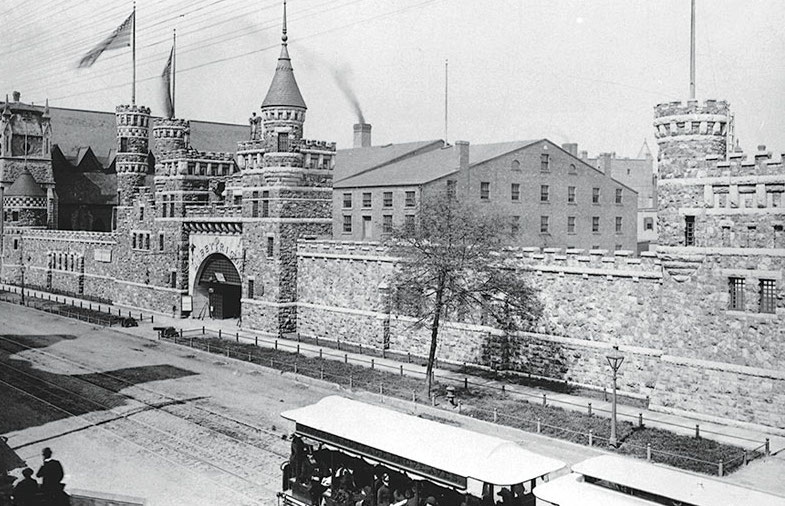

In 1889 Confederate steamship veteran turned candy magnate, Charles Gunther, bought the former prison and shipped its 600,000 bricks on 132 rail cars to Chicago where it was reconstructed and renamed the “Libby Prison War Museum” (Wheelan, 224). To give the structure some showbiz appeal, the architect added a medieval castle wall to the front of the building[2]. Gunther envisioned himself as another P.T. Barnum and filled the museum with his collection of Civil War memorabilia. Scattered among these were oddities such as a snakeskin described as that of “the serpent that tempted Eve in the Garden of Eden, with testimonials to its authenticity,” shrunken Inca heads, and Andrew Johnson’s iron (Bernstein, 200). There was even a gift shop where visitors could buy souvenir Libby cigars, Abraham Lincoln silver spoons, medals, worthless Confederate money, replica bullets, and of course Gunther candy (Marten, 146). The museum was a hit with veterans and the public alike and became a feature of the Chicago World’s Fair, but when the Civil War generation began to die, so did interest in the prison.[3]

Back in the Smokey Mountains of Tennessee, the illiterate teenager who had enlisted in the Union Army by signing with an “X,” learned to read and write, taught himself law, passed the bar, and eventually was appointed the court circuit clerk in Sevierville. William Chandler developed a passion for the written word. As if he were making up for lost time, he signed his name repeatedly on the flyleaf of each book he owned, and kept detailed accounts of purchases and loans, along with a collection of amusing quotations in numerous small pocket journals. His obituary in the Knoxville Journal referred to him as “a great reader” and my grandmother described him that way too (Chandler, 4). Later in life he taught himself Greek, Latin, and some German so he could read even more.

When my narrative of tragedy and triumph was over, my daughters were less then impressed and more interested in returning to their audiobook. Grandpa Chandler’s exploits were weighed and found wanting compared to Percy Jackson’s adventures. This was a disappointment, of course, but not totally unexpected. After all, my audience of two excited ten year olds was more interested in Dollywood Splash Country’s waterslides than civil wars. Also, it wasn’t the first time they’d heard some of these stories.

I’m a big believer in knowing family history. It’s a mantle passed down from my great grandmother, W.C.’s granddaughter, Cleopatra, who had the good fortune to be born when Grandpa Chandler was in his Classics phase. Our walls at home are covered in old family photos to the point that my girls accuse me of decorating it “like a Cracker Barrel.” I try to pepper conversations with family anecdotes, just like my grandmother did, in the hopes that they will remember relatives who lived long ago or far away, especially now that we ourselves are living far away in Canada.

Occasionally I’m accused of favoring change over tradition when it comes to the church[4], however there are many church traditions I find meaningful. The Eucharist is a tradition central to the expression of our faith, and I enjoy candlelight on Christmas Eve and sunrise services on Easter. I also love digging around in church attics and archives, uncovering old photos of past congregations in crinolines and bell-bottoms. I look forward to the annual untangling of Christmas ornaments made decades ago by earnest WMU ladies. One of these days, I may even uncover the rest of that Garden of Eden snakeskin behind some old hymnals in the church basement.

But, I confess, I’m also a big proponent of change. Transformation is where the gospel of Jesus Christ leads us. The Holy Spirit is constantly pushing the envelope in the New Testament and continually pushing us out of our comfort zones even now. Even in the Old Testament the prophet Isaiah (43:19) reminds us that God is at work doing a “new thing” that springs up before us. God promises that where there was once wilderness, there will be a way through, and where there was nothing but desert, a river will flow.

“Transformation is where the gospel of Jesus Christ leads us. The Holy Spirit is constantly pushing the envelope in the New Testament and continually pushing us out of our comfort zones even now.”

However, church traditions can easily become church idols. When they do, rather than being the compass that points a church toward God, without new infusions of meaning and intentionality, they can lead God’s people in a spiral of self-referential banality. Similarly, Charles Gunther’s self-proclaimed “Shrine of Patriotic Memories” never became the deterrent to war that Lincoln hoped. Gunther cashed in on Civil War sentimentality, and cashed out when he saw an opportunity to remake the museum into the new Chicago Coliseum. The venue hosted political conventions, the first roller derby, professional hockey games, wrestling matches, and rock concerts for a few more generations, before it was demolished in 1982 (Bernstein, 201).

Unlike the Libby Prison and Museum, Dolly Parton’s one room childhood home with its tin roof and outhouse is still standing at the end of an isolated gravel road along Locust Ridge on the outskirts of Sevierville[5]. Dolly could have decamped to Nashville, leaving the cabin and rural Tennessee behind when she hit the big time, but she didn’t. Inspired by her childhood, Dolly Parton has used her resources and connections to transform eastern Tennessee. Her Dollywood theme parks not only provide employment to an area in need of economic development, but the park’s Craft Preservation School keeps Appalachian traditions like pottery, woodcarving, leatherworking, and blacksmithing alive through classes and workshops.

We counted ourselves as beneficiaries of Dolly’s generosity, when the twins were gifted books from her Imagination Library. Founded in honor of her father who, like W.C. Chandler grew up illiterate, this organization partners with local groups all over the US, UK, Canada, Ireland, and Australia to give books to children on their birthdays from infancy until they start school, regardless of income. When the librarian in Oliver Springs, Tennessee gave us a few of the books that the Imagination Library had sent for families in need, it meant so much to me. I felt like someone cared, like Dolly herself cared and valued my children, when so many others had not, and in that moment, I really needed that encouragement. Because at the time we received our books, were among those with no income and it was nice to feel we weren’t forgotten.

And that’s why I drag my daughters to Sevier County and bore them with stories about family history and Dolly Parton. My hope is the girls will find examples of strength and perseverance in these stories, and might be as inspired by them as they are those of Percy Jackson one day. If William Caswell Chandler could survive a Confederate prison, teach himself law and Latin, then we can get through middle school (Lord, hear our prayer) and whatever else life throws at us. I want my children not only to know where they came from, but also to recognize their privilege and pass it on. There are plenty of people even now growing up just like Dolly and W.C. who deserve to be heard and helped.

“I want my children not only to know where they came from, but also to recognize their privilege and pass it on. There are plenty of people even now growing up just like Dolly and W.C. who deserve to be heard and helped.”

“

It’s why churches too need to revisit and re-examine their traditions and the stories they tell themselves, especially in this time of unprecedented change. What do they remind us of and point us toward? Where do they belong? Perhaps some of these traditions should be consigned to a “Shrine of Ecclesiastical Memories.” While, sentimental mementos of a congregation’s life together, they are not necessarily useful for making a way in the wilderness. Others, primarily those of church identity that emphasize exclusion, primacy, and merit over equality and grace, let’s face it, should have been demolished in 1982. But those traditions and stories that remain, the ones that reflect the greater story of the gospel, have the potential to bring a river of life to the deserts of devastation left by poverty, war, and inequality. They have the power to propel us forward into an uncertain future, precisely because we can be certain that God, who was with us in our darkest prisons, has freed us and goes before us to light our way that we might be a light and conduit of freedom to others.

[1] It’s a little known, or well-suppressed fact that eastern Tennessee fought on the side of the Union.

[2] Less “Rat Hell” and more “Dix E. Cheese” (Thank you, Todd Thomason.)

[3] The Chicago Historical Society purchased the Civil War artifacts from the Libby Prison War Museum after Gunther’s death in 1920. View the online here.

[5] I will probably drag the girls to see it next time we are in town, or at least usher them through the Dollywood theme park replica of Dolly’s rustic home.

Sources:

Bernstein, Arnie. The Hoofs and Guns of the Storm: Chicago’s Civil War Connections. Lake Claremont Press, 2003.

“Chandler”. Mortuary. The Knoxville Journal. Knoxville, Tennessee. November 18, 1926 page 4.

Marten, James Alan. Sing Not War: The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America.University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Porter, David Dixon. Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War. Appleton and Company, New York, 1885.

Talkov, Andrew. “The Story of Virginia, an American Experience.” Virginia Museum of History and Culture. December 22, 2010.

Wheelan, Joseph. Libby Prison Breakout: The Daring Escape from the Notorious Civil War Prison. Public Affairs, 2011.