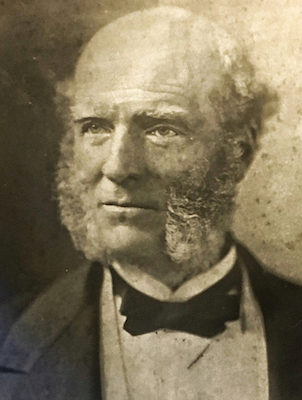

On a recent Sunday afternoon trip, Kristen and I visited the village of Rugby, Tennessee, a 19th century experiment in egalitarian society founded by the writer-politician Thomas Hughes, best known as the author of Tom Brown’s School Days. The town is named after the same British boarding school that inspired the setting of his best-selling book.

The concept of utopias like Rugby intrigues me. While not unique to the United States, the open frontier and pioneering spirit of nineteenth century America provided opportunity for social experimentation that didn’t readily exist in much of the Western world. Concurrently, the Industrial Revolution began transforming and disrupting American life in dramatic ways through mechanization. Rapid economic and geographic expansion created new excesses of wealth, pollution, and poverty and imposed repetitive, dehumanizing forms of labor upon the masses. Dreamers and intellectuals, such as Thomas Hughes, sought ways either to remedy or escape these social effluents and help those whom change left behind.

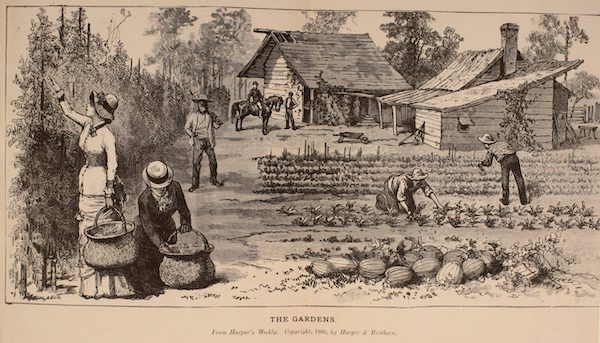

One such group were the younger sons of privileged families like his own, typically excluded from the family inheritance except for a modest allowance. Thomas Hughes imagined Rugby as a colony where these younger sons of affluence, together with a contingent of Americans also looking for an alternative to the status quo, could find a sense of purpose and make a meaningful life for themselves. Guided by the principles of Christian socialism, Hughes imagined Rugby as a place free from the prevailing hierarchies of British (and American) classism. Equal opportunity would be assured because every resident of Rugby would have a stake in the settlement’s enterprises and thus share in the community’s collective success. Life in Rugby would be rigorous yet refined.

Hughes personally bankrolled the venture; however, the idea of Rugby never caught on broadly. The thought of becoming communal farmers in far-flung Tennessee didn’t hold great appeal for many leisurely English aristocrats. Overly romantic choices, such as entrusting a poet friend with location scouting for the new settlement, also created liabilities for the community. Idyllic land isn’t necessarily arable land and so a tomato canning plant, sure to be a steady source of revenue for the fledgling village, had to be abandoned because the settlers simply could not grow enough tomatoes to keep it going. Then there was bad luck. The new Cincinnati-Chattanooga railway line allowed Rugby to operate as something of a resort town, attracting northern vacationers to its European styled Tabard Inn. Tragically, the Tabard burned down in 1884, a mere four years after the colony’s founding. A Typhoid outbreak around that same time also weakened the settlement.

Despite these miscues and setbacks, Rugby did manage to find its feet, if only for a little while. Four hundred residents called the village home at its peak around 1890 and they enjoyed a level of cultural vibrancy unheard of in communities of comparable size, especially in rural Tennessee. Rugby possessed its own library and weekly newspaper. Tennis, croquet, swimming, and (fittingly) rugby were available to all as recreational pastimes, and a drama society provided the community with regular entertainment. Life in Rugby was indeed rigorous yet refined. In the end, however, it all proved unsustainable. Thomas Hughes died in 1896 and by 1900 most of the residents had relocated. Today an historical trust helps to preserve and restore Rugby’s surviving structures.

Walking through the old church yard and back up the main road, I found myself both scoffing at the folly inherent in the very idea of Rugby and longing for a time when men like Hughes dreamed such dreams. Currently our wealthiest and most influential business leaders are pouring their aspirations and fortunes into indulgences such as space tourism: 10 fleeting minutes of weightlessness and breathtaking views for $450,000 per seat.[1] There are as many private charitable foundations as there are multi-millionaires, and they do good in the world; but they haven’t transformed the socio-economic landscape in any significant way. And they won’t. As Anand Giridharadas has demonstrated in his book Winners Take All,[2] modern philanthropic structures and methods actually serve to maintain the status quo rather than challenge it.

That status quo is the product of a tech revolution every bit as disruptive as the industrial one that swept through Hughes’ time, and it has cut similar swaths of advancement and destruction. A select few have made unprecedented amounts of money while millions more have been left behind, shut out of prosperity by a lack of job skills or trapped in the mire of stagnant wages. Meanwhile, many who are succeeding professionally and materially in this environment are floundering personally. A loneliness and an emptiness lurk behind the brilliant LED glow of twenty-first century America, and the artificial light is pervaded by fear. Fear of losing a competitive edge. Fear of not meeting market expectations. Fear of slipping down the social ladder. Fear of not having as much as the next guy.

“High-rise luxury condos soar into the sky, but they don’t reach for it because they don’t exist for anything higher or beyond themselves.”

This emptiness is evident in the structures and neighborhoods we build. Impressive new housing complexes are going up coast to coast, pushing our cities ever outward and upward. Yet, despite their size and innovation, their presence is rather inconsequential except in relation to traffic patterns. High-rise luxury condos soar into the sky, but they don’t reach for it because they don’t exist for anything higher or beyond themselves. A contemporary high-rise’s only purpose is to provide comfort for its residents and profit for its developers. A new development of single family homes near my in-laws holds an eerie silence even though all the houses in the first phase are, to my knowledge, occupied. I rarely see people outside in their spacious yards. Many days the street feels like a movie set waiting for the film crew to arrive.

Here, in this remnant of nineteenth century Rugby, a more substantive and hopeful spirit lingers, even if the community never quite became what Hughes and others hoped and dreamed that it would be. A spirit to expand access to life’s joys and refinements rather than restrict them. A spirit to experience and achieve more than material gain. A spirit worth remembering because utopias like Rugby are, at their core, exercises in imagination.

Philosopher Matthew Stewart asserts that one of the features of the meritocratic class structure that shapes so much of contemporary American life is a fundamental lack of imagination among the people most engrossed in its priorities and pursuits.[3] As wealth continues to be concentrated in the hands of fewer and fewer people (the “1%”), success becomes more difficult to achieve for everyone else. The path to the top is narrowing, and the odds of “making it” are increasingly becoming longer. Nevertheless, a majority of the people who inhabit the US upper middle class (the “9.9%,” as Stewart calls them) double down on the system rather than bucking it – and are miserable as a result. As a society, as a culture, as an economy, we are stuck in no small part because we cannot envision an alternative way to strive, to be.

“As a society, as a culture, as an economy, we are stuck in no small part because we cannot envision an alternative way to strive, to be.”

The legacy of places like Rugby and reformers such as Thomas Hughes should encourage us that such innovation is possible – hard work, but possible. Along with creative inspiration, these experimental communities also offer us lessons through their practical struggles and missteps. They remind us that in order to achieve new outcomes, we have to design new structures and new systems as well as set new priorities. We have to develop the logistics to support and implement our ideals, principles, and longings. This is one of the surest ways the past holds the key to a better future. In the words of another dreamer, Victor Hugo: “There is nothing like dream to create the future. Utopia to-day, flesh and blood tomorrow.”

For all the broad applications of Rugby’s legacy in 21st century America, I cannot help but think first and foremost of the institution we know as the church. As a disciple of Jesus and pastor to others seeking to follow Jesus, the words of Victor Hugo quickly give way to the voice of the prophet Isaiah in my mind: “I [the LORD] am about to do a new thing; now it springs forth, do you not perceive it?” The God of the Christian Scriptures is a God who does new things, a God who restores and redeems, who forgives and transforms, a God who never leaves well enough alone but is at work making all things (all people, all creation) new. A God who, through the voices of the prophets and the witness of the apostles, invites God’s people to join God in that newness.

The articulation of what can be – of what will be because God declares it – is what renowned Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann terms a holy act of prophetic imagination. These proclamations, in Brueggemann’s analysis, not only describe what will be but also catalyze its creation. This is why the prophets of God call God’s people to repentance – precisely so they can turn away from the old ways and take deliberate, concrete steps toward this new, articulated reality: a new way of being, a new way of ordering and undertaking life in relation to God, the world, and each other. An outpost on the event horizon of this new world, a people grounded in the spirit and valuations of this new world that is “already but not yet” – that is what the church is called to be.

And that is precisely what we see the church actively striving to be in the New Testament Scriptures, especially early on in the Book of Acts. The communal life of the nascent church in Jerusalem is radically different from that of the surrounding cultures, both Jewish and Gentile. Grounded in worship in the Temple, Jesus calibrated the members of His community to a new set of weights and measures. Worldly designations held no sway. They not only regularly shared the table together in Christ’s name, they also regularly shared everything else they owned in Christ’s name (Acts 2:44-46). As a result, no one in the Jesus community went without, the community flourished, and God’s newness continued to break into the world through them. Such holistic transformation born of interpersonal commitment, not simply individual trinitarian faith – that is the thrust of the gospel. To riff on Jesus’ words in Mark 10:42, as the Gentiles do (i.e. as the world does), as the Pharisees do (i.e. as the religious establishment does) lording it over others – it will not be so with you.

Sadly, that is no longer the case. In most 21st century churches, that new spirit, that new creation, is nowhere to be found. There is a lot of talk about God and Jesus, but in the church’s structures and practices the worldly metrics of American consumer capitalism hold sway. Churches judge their “success” (and that of other churches) based on numbers. The bigger the budget, the larger the attendance, the greater the number of campuses, the “better” that church and its pastor are deemed. Personal status in the world carries over directly into the church so that church leaders tend to be corporate leaders, and wealthier members have weightier votes. Likewise, political ideology drives the beliefs and convictions of congregants more than spiritual formation. In many towns, especially in southern states such as Tennessee, there is a church on every street corner; but there is little, if any, noticeable impact on life in those towns because of this proliferation. Want and need abound. Social distinctions hold firm. People aren’t better off because those churches are there. In my pastoral experience, a majority of church people prefer comfortable sameness to God’s newness. The new thing(s) the God of Scripture is up to aren’t breaking into the world through these institutions. It’s time for a change! And the past holds the key to the future.

“In my pastoral experience, a majority of church people prefer comfortable sameness to God’s Newness.”

What the 21st century American church needs – and what 21st century America needs from the church – is to reconnect with and reclaim its God-driven prophetic imagination. To do so, Walter Brueggemann suggests that churches need to reposition themselves as “prophetic subcommunities” in tension with the dominant culture rather than as civic intuitions chaplaining the dominant culture. This is no easy shift. It requires a patient and determined “shared willingness to engage in gestures of resistance and acts of deep hope.” 4 It requires upending the status quo within the congregation and assessing congregational life according to Jesus’ alternative rubrics of success. Such a shift will also entail designing new systems and developing new structures to set new priorities in motion and keep them going, because the current institutional model of church driven by committees and membership rolls cannot support or sustain this work. In other words, we’ll have to dream it, then build it.

The good news is that we have a long and powerful legacy to draw on, in Scripture and in history, to help us imagine what such a new church would look like. This shift is actually not about becoming something new. Rather, it’s about returning to our roots, to what we used to be, to what we’ve always been called to be. A new-old church is what the present times call for to reconnect us to God’s ongoing mission to make all things new.

[1] The current starting rate for a ticket on Virgin Galactic, up from the initial price of $250,000 per seat. Richard Branson predicts tickets will eventually go for as little as $40,000 each. In another ten years or so. https://www.the-sun.com/lifestyle/tech-old/3249700/virgin-galactic-cost-fly-space-richard-branson-launch-latest/

[2] Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World. Penguin Books, 2020.

[3] https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22673605/upper-middle-class-meritocracy-matthew-stewart

[4] Walter Brueggemann, The Prophetic Imagination, introduction to the second edition.