The intense national debate over the removal of Confederate monuments often boils down to questions of intent and affect. What was the original intent of those who erected these monuments? What effect did their presence have on the surrounding community? Are these grandiose displays the product of history or attempts to influence historical memory? A new study out of the University of Virginia’s Department of Psychology, Equity Center, and Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy hopes to provide some answers.

Social psychology researcher, Kyshia Henderson, the lead author of “Confederate Monuments and the History of Lynching in the American South: An Empirical Examination,” has uncovered a correlation between the presence of Confederate monuments and the prevalence of lynching in southern counties. Lynching was not just about punishing an individual; it also served as a means to terrorize the wider Black community and undermine civil rights advances before and during Jim Crow. The question before Henderson became, “Could these public monuments be serving the same purpose as public lynchings?”

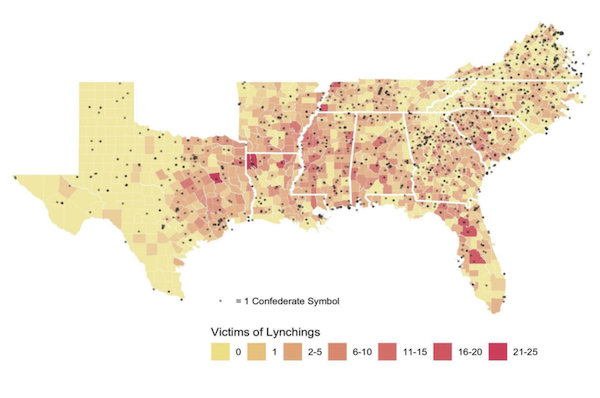

The research team began by examining the speeches given at the dedications of 30 such monuments for racialized language and found almost half of the speeches studied used “explicitly racist language.” Next they looked at the number of reported lynchings per county that occurred between 1832 and 1950. They then compared this data with the total number of Confederate memorials in these counties. Even when population changes and other variables were taken into account, the results indicated that the number of lynchings was “a significant predictor of the number of monuments in a given area.”

“Where inequalities and injustices exist, monuments often perpetuate them.”

While Henderson is not able to prove cause and effect, she can say with certainty that the same racist attitudes that led to the lynchings were indeed present in these communities when the memorials were built. “Where inequalities and injustices exist, monuments often perpetuate them,” said the report. More than a glimpse into history, the research team hopes that cities grappling with what to do about their Confederate monuments will benefit from these findings. Having determined that the statues are, in fact, the products of hate, communities can move past questions of intent and toward questions of what what should be done to replace them.

This interest in the relationship between Confederate monuments and their communities is also fueling Kyshia Henderson current research project: an examination of present-day attitudes towards Confederate symbols. Her continued research promises to be even more compelling as cities, schools, and churches debate the future of Confederate memorials and their impact.

Further Reading

Brockell, Gillian. Washington Post. “Counties with more Confederate monuments also had more lynchings, study finds”

Tor, Erin. UVA Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy “New UVA Study Finds Correlation Between Lynchings and Confederate Monuments”

O’Hare, Erin. Charlottesville Tomorrow. “Confederate memorials are associated with hate’ — New UVA study shows ‘significant’ correlation between lynchings and monuments“

Via Ex Machina contributing writer, Rachel Loughlin, shares her experience as a witness to the events surrounding the protest and removal of the Robert E Lee Monument in Richmond, Virginia through her poems Graffiti and Gray.