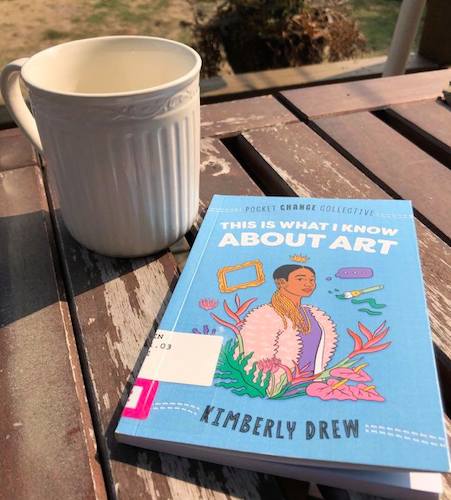

Kimberly Drew’s book, This is What I Know About Art, is a tiny book at 63 pages, and certainly does not reflect all that the former social media manager of the Metropolitan Museum of Art knows about the subject, but is a treasure trove of insight. Published by Penguin Random House, What I Know About Art is a volume in their Pocket Change Collective – a series of books highlighting artists and activists that are geared towards teens and young adults. If you, like me, are not in that demographic, don’t let that stop you from grabbing a cup of coffee and settling in with this eye-opening book. Read it once to absorb Drew’s experience as a black, queer woman finding her feet in the white, male dominated art world, and then read it again, with pencil in hand, to jot down all the names of the Black contemporary artists you don’t know, but need to know. A self-proclaimed curator of “black art and experiences,” Kimberly Drew has carefully chosen the artists she introduces to her readers, and I am looking forward to exploring and expanding my list.

Kimberly Drew begins this introduction to Black Contemporary Art with her own exposure to the genre as a student struggling to find her place at the elite, and very white, Smith College. Originally a math major at Smith, Drew changed her major to Art after a paid summer internship at the Studio Museum in Harlem. And that sentence right there, the one you just read, is one of the many reasons why white people need to read memoirs by people of color. Because, as a white person who changed her major in college, I read that sentence and thought “Ok, a little paperwork, a little shift in course load, I get it.” But I don’t. Drew explains, “For so many people of color, we feel like we don’t have the luxury of exploring liberal arts.” I have a few liberal arts degrees, but I had never before considered the privilege inherent in pursuing them.

Kimberly Drew is equally adept at exploring the richness of on Black Contemporary Art as she is at drawing you into her own experience. Even if you come to this book knowing nothing about art, you will find yourself in compassionate, considerate hands. Her observation, “The more art I saw, the more I wanted to share it with others,” is really a mission statement. You can feel Drew’s excitement as she discovers new artists, visits art shows and gallery openings, and writes about it for her followers on Instagram and Tumbler. I had to stop and look for an image of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (Perfect Lovers) when she called it the “most romantic artwork I had ever seen.” And because Kimberly Drew does such a great job explaining this piece of conceptual art, I find myself not only persuaded she might be right, but able to extract from the work my own personal meaning. The same is true of Rodney McMillian’s red leather chapel installation, “From Asterisks in Dockery,” the centerpiece of the Whitney Museum’s “Blues for Smoke” exhibit. Again, I found myself down a rabbit hole, but a welcome one, reading about this impactful work of art. The lack of accompanying images is a glaring shortcoming of the book but Kimberly Drew’s Tumbler, https://blackcontemporaryart.tumblr.com/ is available to remedy that.

For Kimberly Drew, art and activism are two sides of the same coin in that “both allow us the space to be curious and learn.” In her journey through the art world, Drew witnesses not only the marginalization of art by artists of color, but the ways in which society as a whole marginalizes people of color and those with disabilities. After a scathing critique of an exhibit’s lack of representation lands her in trouble, she realizes that when pushing back against racism and exclusion, it’s not enough to be angry. It’s just as important to be strategic – something those involved in the early days of Civil Rights understood, and we would do well to remember. After her experience working with a hearing impaired artist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Drew realizes organizations need to do more to improve accessibility at all levels for those who are not readily welcome. She encourages us to ask who is and who is not “in the room” with regards to race, socioeconomic status, disability, etc. This is something we should all take note of the next time we’re in a meeting for work, church, or organizing a protest.

Drew ends the book where she began it, struggling to find her place – wondering if her efforts to change an institution from the inside are worth it, or if that time and energy would be better spent working at the grassroots level. What do you do when you love something like art so much that you “want to see it change for the better?” I look forward to seeing what Kimberly Drew will do next at the intersection of art and activism. And in the meantime, I have a list of Black contemporary artists to help me find the answers to my own questions about art and activism.