Sermon Text from Luke 1:39-56

Last week we began this sermon series with a non-Christian sculpture beautifully and painstakingly carved by a non-Christian artist. The church was most likely the furthest thing from Bill Reid’s mind as he and his team created The Spirit of Haida Gwaii. Even so we found lessons and inspiration for the church in the dynamic composition and mythic passengers of that wondrous canoe.

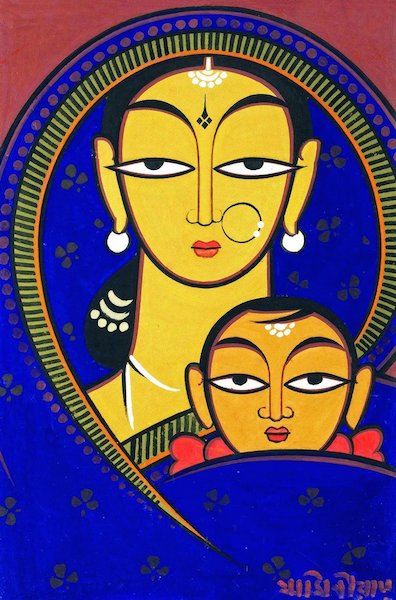

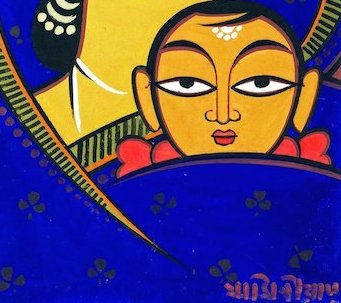

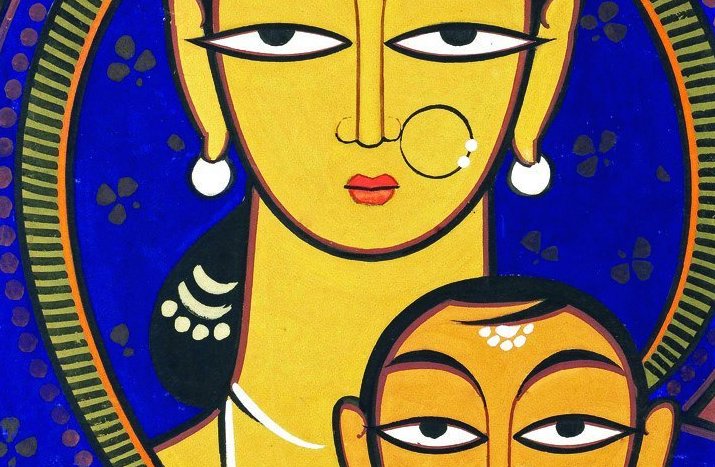

Today we turn to a quintessential Christian subject – a portrait of the infant Jesus and his mother, Mary – but one framed and interpreted by a non-Christian artist from India, Jamini Roy. It may seem strange at first to wonder, much less care, what a Hindu might have to show us about Jesus; but as with The Spirit of Haida Gwaii, there are lessons here we would do well to take note of.

God is bigger than our familiar horizons. The Holy Spirit is alive and well out there in the world, beyond us and apart from us as well as within us. If we really are interested in and serious about understanding how God is at work, what God wills and intends, then we have to listen as well as speak. We have to be hearers as well as doers of the Word (James 1:22), because we do not know or understand it all. In the words of the Apostle Paul, we “see through a glass darkly” (1 Corinthians 13:12) and we need the divine, heavenly light in others as much as they need the divine, heavenly light in us.

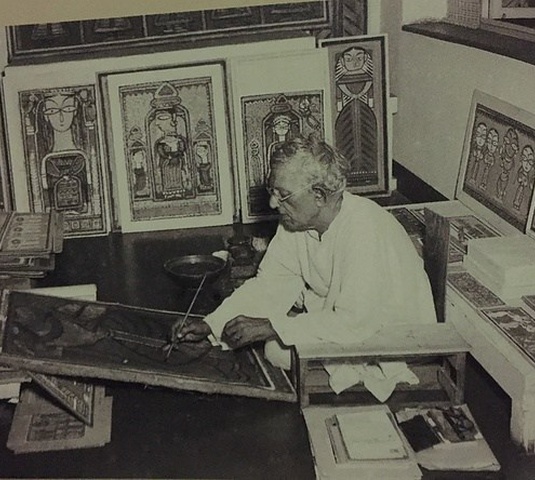

And there is light for us shining through the eyes of Jamini Roy, India’s preeminent modern artist, whose story is as fascinating as his art. Born in 1887 in a village (Beliatore) in West Bengal to a landowner family under British colonial rule, Roy inherited his talent and love of art from his father, who worked for the government but resigned to pursue an art career. Jamini left his village at age 16 to study art in Calcutta under Abanindranath Tagore, where he was trained in the the British academic tradition and studied European modernist techniques.

At the beginning of his career, Roy painted portraits for commission and was good at it. He was sought after. But he wasn’t satisfied. He wanted more; he was searching for more meaningful engagement, more meaningful application of his craft.

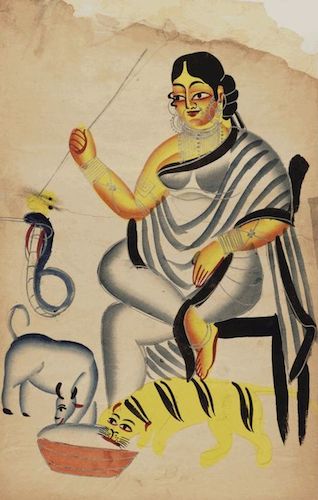

Then in 1925 he was profoundly moved by the Kalighat folk art paintings he encountered outside the Kali temple in Calcutta. His heart was drawn to the style, the expression, the colour. Jamini Roy knew he had discovered the kind of art he wanted to pursue – to paint in the native spirit of his country.

He also knew that, like these paintings displayed outside the temple, he wanted his art to be accessible to the public, to the common people.

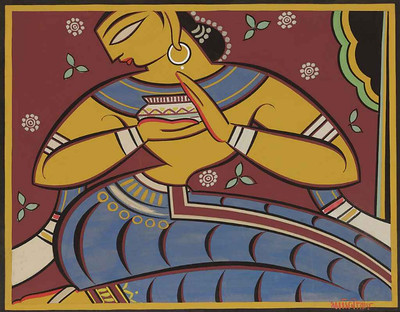

Roy spent the next few years studying the idioms and history of the Kalighat style, developing his technique, and finding his artistic voice. He took inspiration from East Asian calligraphy as well, working to strip away unnecessary ornamentation and detail – visual noise – from the backgrounds of his pieces, honing in, zooming in on the central subjects. In so doing, he developed the signature style he is known for: a reinterpretation of traditional Indian art through the lens of modern art.

By the 1940s, his work began to catch on among what we would term middle class Indian families. Pride in Indian culture was growing as the independence movement gained steam, and even as his reputation grew along with it, Roy never sold his paintings for lavish sums. Mostly he cared that his art would find a home where it was appreciated and valued. In fact, there are stories of him buying back his paintings when he heard they were being ignored or neglected.

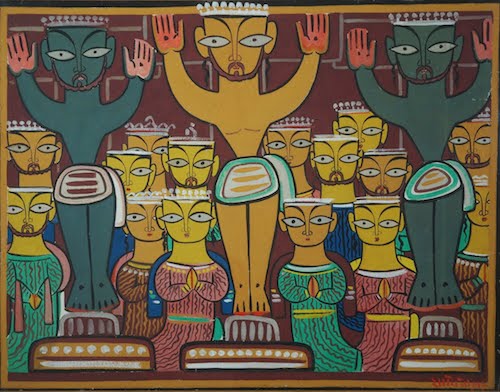

What surprised Roy was the interest the European community began to show in his art that celebrated indigenous Indian culture and turned away from familiar European tropes. In 1938, Roy became the first Indian artist to have his work displayed on a British-ruled street in Calcutta. By the 1950s his art was on display in both London and New York.

Jamini Roy didn’t just adopt and pursue a traditional Indian artistic form and idiom; he sought to reclaim the medium of his art from Western colonialism. As he moved ever more thoroughly in the direction of folk art, he eventually abandoned painting on canvas, opting instead for more everyday materials such as cloth and wood. He even turned away from European paints and began mixing his own pigments using indigenous Indian elements, such as mud, chalk, vegetables, flowers, and tamarind seed glue.

Yet, in spite of this intentional rejection of European artistic traditions and materials, Roy remained fascinated, even captivated, by the figure, the idea, the story of Jesus, who is one of the most prolific subjects in Western European art. Roy’s attraction to Jesus reminds me of the quote attributed to Mahatma Gandhi: “I like your Christ. I do not like your Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ.”

Roy would paint many iconographic renditions of Jesus showing Him as a teacher, as host of the last supper, and as the rejected yet revered Messiah hanging on the cross. But, judged by the number of renditions, the infant Jesus in the arms of his mother, Mary, may have been his favourite.

The Madonna and Child is, of course, one of the most common and familiar motifs to be found within the Western European canon of Jesus painting. And what I love about Jamini Roy’s treatment of this motif is that it is simultaneously familiar and alien. As soon as you see it, you recognize that this is Mary and Jesus, even though it is unlike any rendition of the Madonna and Child our Western eyes have likely ever seen. Which is why it is so important for our Western eyes to see it – to consider this new angle, this alternative perspective. The portraits of Mary and Jesus that we’re accustomed to from Christmas cards and museum catalogues are interpretations as well as depictions, and they obscure as much as they reveal.

Many of the most familiar images of Mary and the baby Jesus prompt us, whether we are conscious if it or not, to approach her – and Him – as paragons of peace and tranquility, epitomes of Western conceptions of beauty and domesticity. Mary is projected as the ideal humble and submissive woman. Jesus is sentimentalized as the “holy infant, tender and mild.”

But in this Madonna and Child, Jamini Roy gives them both an edge. This is a Mary not to be trifled with. This is a Jesus who looks like He knows what you’re up to. Nothing about this Mary is diminutive or infantilized. Jesus is – and appropriately so. He is an infant who looks like an infant here. (I love the wisp of hair on His forehead). It may seem odd to point that out, because what else would Jesus have been when He was first born, the same thing all of us were when we are first born.

But we don’t actually like to think of Jesus as an infant, as helpless and dependent, not really. It makes us uneasy.

Which is why, in a lot of Western European art, baby Jesus looks like a toddler with an aged face, sometimes even a geriatric face. It’s a symbolic flourish to connote unnatural wisdom, but in the process it also robs Jesus of an important piece of His incarnational identity.

Something else I love is that, while Jamini Roy is translating and reinterpreting a Western European subject into a thoroughly Indian context, he remains respectful and true to the source in ways even he may not have fully understood or appreciated.

He has structured this portrait like a Byzantine icon, and keeps with the traditional blue and red colours associated with Mary and Jesus in Christian iconography. But he infuses those traditions with strong, clean, bold lines and earthy colours – colours created from pigments he himself mixed from ingredients native to his region of India – that add an extra incarnational dimension to the painting.

Mary’s outer blue cloak (representing the colour of the sea and the sky, the colour of earth) swirls around them both. Gold hash-marks evoke a halo but also serve to guide our eyes around the portrait, ending (or beginning, depending on where you start) with Jesus’ face. The halo, like Mary’s garment, encircles mother and son, framing and uniting them.

All we can see of Jesus’ garments are His shoulders as He is fully enveloped and protected by His mother. But from the little we can see we know His garment is red, which is the colour of heaven, the same colour that fills the upper corners of the painting, hinting that we would find heaven all around if we could zoom out and see beyond Mary and the Christ Child.

This interplay between red and blue, heaven and earth, symbolises and evokes the miracle that occurred in Mary’s womb: Jesus, the heavenly Son of God, taking on, becoming incarnate in earthly, human flesh.

I also love the eyes. Large eyes are a trademark of Roy’s style but these aren’t just any eyes, transferred from his other work. They’re contemplative eyes. Penetrating eyes. Eyes that see you, and see through you. Eyes that can’t be fooled.

This is a Mary who looks like she has something to say, which of course she does when we encounter her in Scripture. In Luke’s Gospel, Mary is someone who’s on a mission. She’s not the subject of a lullabies. She’s more than an earthly vessel for a heavenly baby; she’s an instrument of God’s redemptive work in the world. She’s not just a mother, she’s a messenger – a messenger from God, a prophet of God, which is how Luke portrays her even if Western artists don’t.

“In Luke’s Gospel, Mary is someone who’s on a mission. She’s not the subject of a lullabies. She’s more than an earthly vessel for a heavenly baby; she’s an instrument of God’s redemptive work in the world. She’s not just a mother, she’s a messenger – a messenger from God, a prophet of God, which is how Luke portrays her even if Western artists don’t.”

Let’s listen closely and carefully to Mary’s words to her cousin Elizabeth as Luke records them:

“My soul magnifies the Lord,

and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior, for he has looked with favor on the lowliness of his servant.

Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed;

for the Mighty One has done great things for me,

and holy is his name.

His mercy is for those who fear him

from generation to generation.

He has shown strength with his arm;

he has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts.

He has brought down the powerful from their thrones,

and lifted up the lowly;

he has filled the hungry with good things,

and sent the rich away empty.

He has helped his servant Israel,

in remembrance of his mercy,

according to the promise he made to our ancestors,

to Abraham and to his descendants forever.”

These are prophetic words; words that uplift us but also snap us to attention. And Luke signals to his readers that we need to pay attention to Mary’s words through the way he structures his telling of the gospel story. Mary’s experience in Luke chapter 1 mirrors the experience of the righteous priest Zechariah, who is the father of John the Baptist. Both are visited by Gabriel. Both are told of wondrous and glorious things God has done and is about to do. And both prophecy about those revelations. We can’t revere the one and ignore the other.

Truthfully we remember Mary’s proclamation more readily that Zechariah’s – or at least we remember the title it has taken on, The Magnificat. We remember it because it has been set to music numerous times down through the centuries and has become a traditional part of the church’s Christmas soundtrack. These musical settings have propagated Mary’s words; but they’ve also domesticated them. They’ve snipped the thorns off her proclamation, much as traditional Western depictions and imaginings of Mary have smoothed and softened her persona, too.

That’s why we need Jamini Roy’s outsider eyes. That’s why we need to see Mary in this different light because, in many ways, this foreign depiction of her it is truer to who she really was. And seeing her more fully should help us hear her more clearly in ways that we don’t (and perhaps even can’t) when we consider her and her story surrounded by all the modern trappings of Christmas, all the accretions of Western, patriarchal culture.

“And seeing her more fully should help us hear her more clearly in ways that we don’t (and perhaps even can’t) when we consider her and her story surrounded by all the modern trappings of Christmas, all the accretions of Western, patriarchal culture.”

Yes, Mary’s Magnificat is a message of praise. It’s also a message of justice – a message of promises kept and changes to come – not just for others, but for us. In that way, Mary’s message embodies and distills and confronts us with the gospel, even before she gives birth to the gospel, to Christ Jesus Himself, to Emmanuel – God with us. And the gospel does confront us. It continues to confront us. Jesus confronts us. There were thorns on Jesus’ words long before there were thorns on His head. We’re still trying to snip off His barbs, too.

But whenever the gospel loses its thorns; whenever we get too comfortable, too familiar, too sure about Jesus, that’s when we wander onto spiritually treacherous ground. We need to hear and look again, anew, at Christ, at God, and at ourselves. This Jesus whom we worship, who has the prophet Mary for a mother, bids us to be born anew in Him, with Him, through Him. And birth is a messy and painful process.

So I’m grateful for Jamini Roy’s Hindu eyes that have helped me – and I hope have helped you – see Mary, the blessed mother of our Lord, and the gospel in a fresh and needed way that pricks our assumptions and gets our attention.

Jamini Roy reveals something else to us that we need to take note of, too. Because God is at work in the world ahead and apart from us, and generations of disciples have gone ahead of us, aspects of the gospel already have traction in the world. Walking in those grooves is where we can find our footing and find our way to openings for our witness and testimony. There is no need for us to blast holes in the walls folks have erected. When we attempt to do that it’s because we’re impatient or because we have some personal need to do some blasting. Rarely if ever does it work. People just build the wall back thicker. The openings are there. We just have to have the patience to do the looking, and the purpose to walk through when we find them. Roy’s interest in Jesus’ birth and sacrifice affirms Shane Claiborne’s observation that “the gospel spreads best through fascination.”

But once we have people’s attention; once we find a foothold; once we step through an opening, we need to listen as well as speak. Because God may very well have shown us that opening for what we have to receive as much as for what we have to give. Because, in Jesus and through Jesus. God is keeping God’s promises; but God is also in the process of inverting and overturning the world’s assumptions and expectations – including those held by us.

“Because God may very well have shown us that opening for what we have to receive as much as for what we have to give.”

Thanks be to God – the One who loves us enough to confront us, to call us to re-birth, to use us as instruments of God’s grace-filled purposes; the One who brings down barriers, reveals pathways, and strips away unnecessary distractions so that we might see and hear clearly the good news of the gospel. Amen.