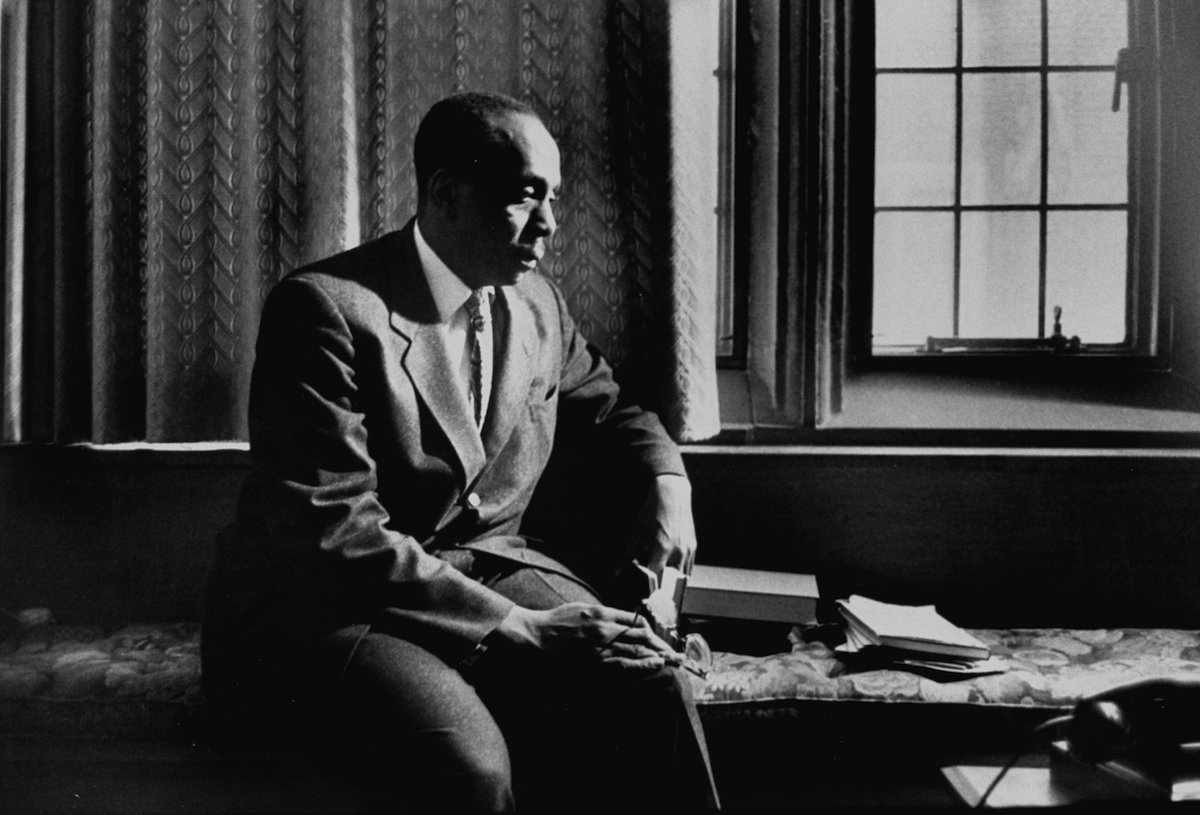

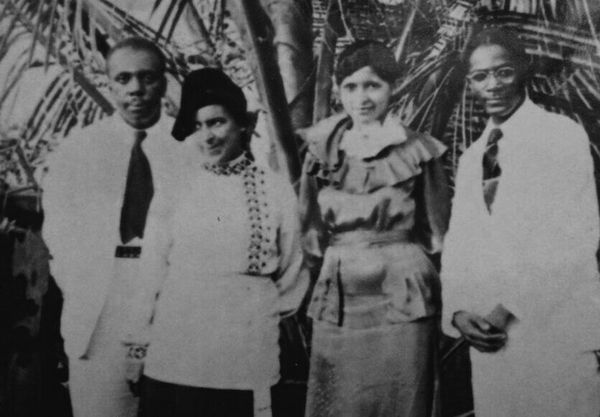

This month marks the 40th anniversary of the death of Howard Thurman (April 10), an early twentieth century African-American theologian, poet, pastor, and activist whose work I am still getting to know. His most well-known book, Jesus and the Disinherited, is a must read for anyone wishing to understand the strata that underlie America’s present socio-religious landscape. Thurman was an intellectual and spiritual forefather of the American Civil Rights movement, a profound influence on Martin Luther King, Jr. and other leaders of King’s generation through his writing (more than 20 in all) and as a faculty member and dean of the chapel at both Howard University Divinity School and the Boston University School of Theology.

For Lent this year, I read a book of Thurman’s previously unknown to me, The Luminous Darkness. The title comes from a description of deep-sea diving one of Thurman’s former students included in a term paper. Once a diver relaxes and lets go of their fear; once the diver’s eyes adjust to the depth and the pressure, they become aware of “the luminous quality of the darkness” and can move into the lower regions of the ocean “with confidence and peculiar vision” (vii-viii). Thurman seizes on this description as a metaphor for the exploration of American apartheid, which is the book’s subject. The Luminous Darkness unfolds as an extended personal essay capturing Thurman’s observations on and personal experience with “the anatomy of segregation” offered as “a testimony as to the grounds of hope for the individual” (ix).

As a tribute to Howard Thurman, I plan to share three reflections on the wisdom contained in this short but deep and thought-provoking book. The second will focus on Thurman’s assessment of how white people respond to segregation as a structure and a concept. The third will concern his assessment as to why the institutional church has served to reinforce that structure and concept when everything in the church’s Scripture and theology should direct it to do the opposite.

In short, this is a book that every white American Christian should read.

But I begin with Thurman’s description of segregation as a “world of meaning.” As I read Thurman’s essay from 1965 in the early weeks of 2021, in the wake of the January 6th assault on the United States Capitol and the March 16th murder of six Asian women in Atlanta, amid questions surrounding the equitable roll out of the COVID-19 vaccines, against the backdrop of the trial of former Detroit police officer Derrick Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, I was particularly taken with Thurman’s analysis of the system of segregation in this vein.

“The [American] South … has been made to feel deeply ashamed and guilty because of slavery and its side effects. It has [thus] been forced to find its significances in the myths and delusions of past grandeur, causing it to back into the future…. [T]he South has a Cause and its Cause was yesterday.” (p. 67-68)

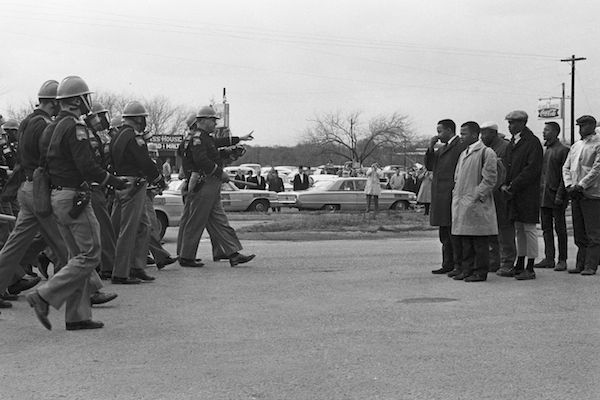

“Segregation… keeps the cult of the South intact and in health. Hence when it is threatened, the fear, the anger, and the guilt become manifest. Any attack on the system is an attack on the world of meaning and reality of the South. Every defense, even to the taxing of all total resources, must be rallied” (p. 70, emphasis added).

Fast forward 56 years, and Howard Thurman’s method of processing the level of resistance marshalled against the Civil Rights Movement helps me make some sense of what is happening now. The hyper levels of fear, violence, and ideological extremism we feel – and struggle to understand – become less confounding when understood as collisions between “worlds of meaning.” A new world defined by liberation, justice, and possibility cultivated by the young and the long-suffering is crashing into the established world defined by white supremacy, patriarchy, and global consumer capitalism. The inhabitants of this established world are fighting back as if the world were about to end because, in a very real sense, the world as they understand it is going to end if the forces of change prevail. From Thurman’s perspective, we shouldn’t expect the resistance to be any less. When worlds collide, the upheaval is seismic precisely because it is tectonic.

“The hyper levels of fear, violence, and ideological extremism we feel – and struggle to understand – become less confounding when understood as collisions between ‘worlds of meaning.’”

There is no way to lessen the tension and the strain. As with past upheavals, the challenges this latest upheaval poses are numerous and daunting, even overwhelming; yet so are the possibilities. That’s why, for all of its troubling revelations and unsettling analyses, Howard Thurman can rightly describe The Luminous Darkness, in part, as a “testimony of hope.”

Migration between worlds of meaning is possible, and I can add my own life story as corroboration of this hope. Over the past two and a half decades, through study, experience, and the building of relationships across the divides of present day American life, I have managed to escape the established world of meaning, which absolutely shaped my upbringing as a white, affluent, American male. This influence was subtle and persistent and rarely blatant, which is what makes it so insidious. My departure is far from complete; but I have certainly achieved enough distance and gained enough altitude to see this world of meaning for what it is and understand the colorful gases of its atmospheres to be toxic and malforming. If I can do it, others can, too. However, that process takes time and results are not guaranteed. More will be required.

Thurman’s qualifier to his “testimony of hope” is telling: hope for the individual. On the structural and systemic level, the realities of segregation’s legacy are more complex and foreboding. United States history since the legislative triumphs of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement has demonstrated just how strong a gravitational force emanates from segregation as a “world of meaning.” Segregation as a codified social structure was dismantled, yes; but as a mindset, a way of seeing and mapping the world, it has since entrenched and adapted. The powers that rule over this “world of meaning” have innovated means of camouflage, engineered new materials with which to construct boundaries, and formulated new strategies for annexing formerly lost ground. Segregation never surrendered. If Thurman is correct, it never will.

“Segregation as a codified social structure was dismantled, yes; but as a mindset, a way of seeing and mapping the world, it has since entrenched and adapted.”

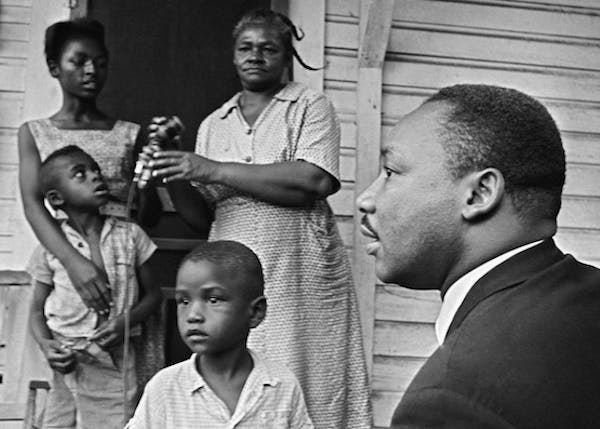

This mutation of the segregation mentality is among the things Thurman feared and anticipated. “The removal of the walls is the first step…. Care must be exercised to see to it that new walls will not be built. One of the things that will make it easier to build new walls of segregation in the form of new kinds of discrimination is what has been aptly called the discrimination gap,” (p 92-93) so named because of the social, economic, and educational gap left between the segregators and the segregated. The abusive imprint left on African-Americans by centuries and generations of slavery and apartheid did not simply vanish once the strictures were loosened. There is physical and especially deep psychological and spiritual damage that must be tended to. In fact, this damage is the very thing that the powers-that-be exploit in order to perpetuate segregation in different forms (e.g insinuations such as, “See, look at all their problems. We don’t want our kids to be influenced by those people.”). Repairing and healing that damage thus becomes a necessity for the second, third, even fourth steps on the journey toward liberation, and it is work that must be undertaken on a societal as well as on an individual level.

Thurman offers no prescription for going about this repairing and healing. That, he writes, is beyond the scope of his essay (p. 93). I must confess that one of my disappointments with The Luminous Darkness is the lack of any concrete recommendation. However, I also recognize the merit of such an omission. If segregation is a “world of meaning,” a mindset primarily rooted in the human spirit (p. 90), no programmatic solution will ever suffice. Thurman insists that transforming the human spirit requires the work of imagination, specifically to cultivate within us the ability to put ourselves into another person’s place so that we can learn to experience each other as human beings (p 99-102). There is not, and cannot ever be, a formula for that type of work.

“Thurman insists that transforming the human spirit requires the work of imagination… the ability to put ourselves into another person’s place so that we can learn to experience each other as human beings.”

To this end, Thurman points to the public pain of the tectonic upheaval as one source of our hope.

“The hate is active, it is uncongealed, it is fluid, volatile, and dynamic hostility. This means that things that have been smoldering are now moving into the open and are thereby becoming available to be dealt with, shared, and treated. They are in reach of the resources of the community. A common agenda becomes available now for the first time.” (p. 84)

In our present context, political and social events of the past five years at the local, state, and national levels have all served to affirm the basic premise of Thurman’s hypothesis. The public resurgence of white nationalism has exposed the resilience of segregation as a mindset and shown it to be alive and well and pervasive in ways that many of us naively thought impossible. Painful and disorienting as that realization has been, we (especially we white and well off) dreamers of a more liberated and just world now have a more accurate measure of the challenge that looms and can fortify ourselves accordingly. That in itself is a measure of progress.

“The public resurgence of white nationalism has exposed the resilience of segregation as a mindset and shown it to be alive and well and pervasive in ways that many of us naively thought impossible.”

That said, here Thurman’s analysis runs into the permutations of 21st century life and feels dated. A defining feature of early 21st century America is the advent of “alternative facts.” Truth and meaning have become as personalized as our podcast subscriptions. The post-modern worldview has challenged and deconstructed our nation’s metanarrative and the internet has come behind it to amplify ideological echo chambers and conspiracy theories in ways that Thurman could not have foreseen in 1965. Mass media worked to further the cause of the Civil Rights Movement in ways that social media does not. In such a siloed public square, a common agenda remains and will remain elusive. The new front in the fight for justice and equality is the campaign to restore a shared understanding of what constitutes reality.

Thurman’s second source of hope is more distant but perhaps the surest hope America has, the one it has leveraged through every phase of progress it has achieved no matter how lurching or incremental: the creative synergy made possible by weighing the disappointment of America’s reality against the aspirations of its ideals. Thurman tells this story:

“While I was in India, when it was still a colony of the British Empire, my Indian friends often tried to make it clear to me that their position in India was a much happier one than mine as an American Negro. I made clear to them the fact that the limitations under which I suffered were in violation of the Constitution of the land and therefore it sat in judgment upon all the civil disabilities from which I suffered. This was for me an enormous basis of hope” (p. 78-79, emphasis Thurman’s).

And so it remains. America suffers many obvious glaring injustices, almost all of them secondary diseases stemming from the toxic mindset of segregation. Often, America is its own worst enemy; but America’s idealistic spirit and innovative drive may be the most resilient in history. They remain America’s greatest assets. If imagination is the key to combating segregation, then no nation is better equipped to engage the battle, even if few nations are as acutely infected.