I wasn’t around in 1963 when Martin Luther King, Jr. told America about a dream he had had. I barely remember the existence of Woolworth’s lunch counters much less sit-ins at those lunch counters. What I know of Dr. King and Civil Rights I have learned primarily from books, teachers, newsreels, and Irish rock stars. Even still, I feel like Dr. King has been with me most of my life. Few people have inspired me more–especially since becoming a pastor. Year after year, I continue to marvel at his ministry and his witness.

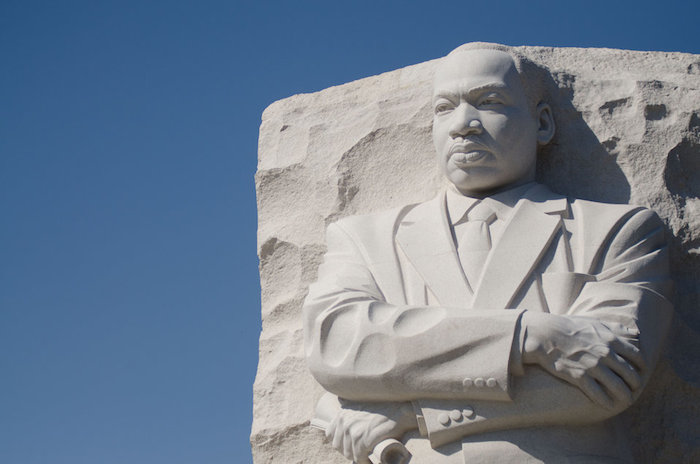

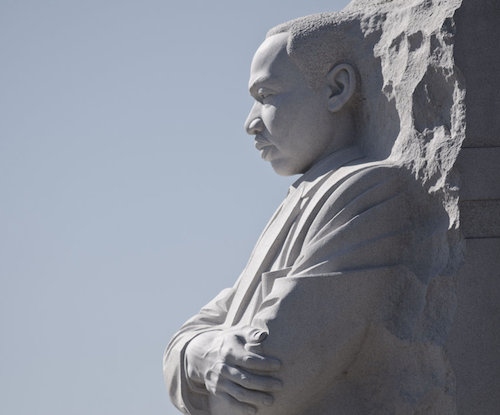

I have also long hoped to God that another Martin Luther King, Jr. would emerge from the shadows that have eclipsed the public face of American Christianity in recent years: someone to reclaim Dr. King’s rich prophetic legacy from the pawn brokers and spin doctors of consumer-driven faith; someone to once again say to America, “Be true to what you said on paper”–all of it, not just hand-picked portions of it; someone to lift our spirits while at the same time calling us to repentance. It has taken awhile, but on this weekend which marks the forty-eighth anniversary of his “I Have a Dream” speech and which was supposed to witness the dedication of his memorial on the National Mall,* I have finally realized that my unrequited hope for this second coming is a sure sign that I have failed to grasp one of Dr. King’s most important lessons: that we ourselves have custody of the distortions that exist in our world. We must decide whether to challenge or foster them.

We tend to forget that Dr. King was only 26 years old when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat in December 1955. He had only just arrived in Montgomery from Boston University with a new wife and a child on the way. “Become conscience of America” was not on his to-do list. He had a congregation to tend, a dissertation to finish, a family to raise and support. When Ralph Abernathy and E. D. Nixon approached him about organizing a boycott, he easily could have said, “What can I possibly do?” as he ticked off the same list of excuses we all carry in our breast pocket. But he didn’t. That choice is what set him on the path to greatness.

“I think we prefer Dr. King to be a haloed saint who descended to Alabama directly from heaven full of power and glory because, as long as we perceive him that way, we can justify our own lethargy in confronting the injustices of our contemporary society.”

I think we prefer Dr. King to be a haloed saint who descended to Alabama directly from heaven full of power and glory because, as long as we perceive him that way, we can justify our own lethargy in confronting the injustices of our contemporary society. We can sit back and wait for another holier-than-me messiah to make things right. In the meantime, then, we can be content to build gated communities, give our backyards an HGTV make-over, or escape to Starbucks.

As we prepare to enshrine Dr. King in the pantheon of our greatest national heroes in Washington, we would do well to remember that the revolution Dr. King led was just that: a revolution. As exceptional as he was, he did not do it alone. Without thousands of ordinary men and women making the same basic choice he did—the choice to stand up for what is right—all the speeches and all the marches would have amounted to little more than stirring words and ceremonial gestures. American apartheid wasn’t overturned because African-Americans stopped riding the bus in Montgomery for a day or two to make a point. It was overturned because they stopped riding the bus for as long as it took to change the system. Week after week after week, those who owned cars gave lifts to their neighbors and formed carpools. Taxi drivers charged reduced fares. Volunteers served as dispatchers to make sure folks had a way to get to work or to school, and everyone agreed to walk if necessary. The community pulled together and shared the sacrifices. And when they succeeded in integrating the city buses, they inspired themselves to continue challenging Jim Crow in other areas of local and national life. The Dream that Dr. King cast was literally carried from Montgomery to Selma to Atlanta to Washington to Memphis, and all points in between, arm in arm and hand in hand.

“Without thousands of ordinary men and women making the same basic choice he did—the choice to stand up for what is right—all the speeches and all the marches would have amounted to little more than stirring words and ceremonial gestures.”

Today the air is once again thick with talk of change and the need for a new direction toward a better future. The mire that surrounds us is of a different consistency than that which Dr. King and the brave men and women of the Civil Rights movement slogged through, but the way forward remains the same: arm in arm and hand in hand. We will be the ones to make change happen…or not. We will stand up for what is right, and make the sacrifices and form the partnerships…or we won’t. And that means that, nearly half a century after Dr. King’s greatest speech, perhaps the greatest threat to the furtherance of his Dream isn’t congressional gridlock, the national debt, a sagging economy, or any of the other usual suspects. Rather, it may very well be our ever-growing love affair with the double, half-caff, no whip, made-to-order comfort of our own personal prosperity – comfort that stands between us and the choice to stand up and do what is right.

* Hurricane Irene postponed the dedication. The ceremony was held instead on October 16, the anniversary of the 1995 “Million Man March” on Washington.

Featured Image courtesy of the Dept. of Agriculture.