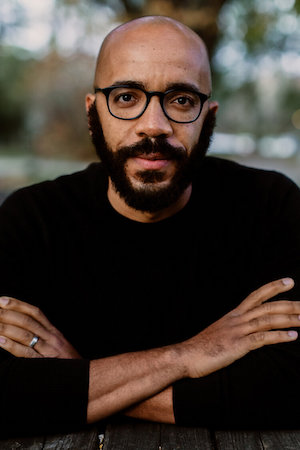

After listening to Clint Smith speak in an interview about his book How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America, I couldn’t wait to read it. In faraway Canada, I pre-ordered my copy of this book on American history. While waiting for its arrival, I tuned in to the live stream national book launch hosted by the Prince George’s County Memorial Library System. A poet and writer for The Atlantic, Smith was once a teacher in PG County and wanted to write a book on slavery that would be approachable and informative. His dedication to reaching audiences outside scholarly circles is why he chose the public library for his book launch.

I knew that library well from our time living in Maryland. While our twin toddlers scurried through piles of picture books, I performed the “library walk of shame” to pay the fines on all our overdue books before checking out another stack. This was just the first instance of How the Word is Passed intersected with my life. The strangest was yet to come.

In this book, Clint Smith braids together American geography, sociology, and history creating a rope that ties together the impact of slavery across the United States. From Virginia to Louisiana, New York, Texas and eventually Senegal in west Africa, Smith visits various historic sites and speaks with tourists, residents, and historians alike about the impact these places had and continue to have on us. As someone who grew up in the shadow of colonial Virginia and cannot pass up the chance to see a historic outhouse, let alone a plantation house, I felt both convicted about my need to read How the Word Is Passed, and conflicted about what the book would require of me once I finished it.

The journey begins at perhaps the most well-known plantation in America, Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia. Like most historically minded Virginians, I’ve been to Monticello, and I will confess that the graceful gardens, the architectural perfection of the house, and the quaint offerings in the gift shop all help distract from “a system of exploitation…a system where people are owned as property and held down by physical and psychological force… (11).” As Smith shows in his book, the obfuscation of the system of chattel slavery is just as intentional and systematic as the slavery itself. And the same is true whether it’s Angola Prison exploiting convict labor or the Tiffany windows at the Blanford Cemetery memorializing the myth of the Lost Cause. Institutions, be they civic or social are invested in maintaining what theologian Howard Thurman calls a “world of meaning” unto themselves. It’s what makes dismantling their inequality so difficult. As the tour guide at Monticello put it, “I think that history is the story of the past, using all the available facts, and nostalgia is a fantasy about the past using no facts…history is about what you need to know…but nostalgia is about what you want to hear (41).”

The Whitney Plantation in Louisiana, Smith’s next stop in the book, stands as a foil to Jefferson’s Monticello. While visitors to Virginia can modulate the depth of their discomfort by choosing whether to sign up for a tour on Jefferson’s relationship with slavery, at the Whitney, there’s no opting out. From the moment Clint Smith steps on to the Louisiana plantation he is literally face to face with the horrors of chattel slavery. An exhibit of ceramic heads on metal stakes stands where the heads of enslaved persons were posted in 1811 as a warning to others who might attempt to rebel. It’s one of several art installations at the plantation raising deeper questions about slavery in the United States, questions that Clint Smith himself is not afraid to ask. He admits as a student he wondered why more slaves didn’t escape conditions like those portrayed at the Whitney and explains that teaching solely “heroic slave narratives” is a way to blame the ordinary men and women who could not escape rather than blame the system that kept them in bondage. “This ordinariness” he writes, “is only shameful when used to legitimate oppression (64).” Teaching about the ordinary lives of enslaved persons, especially women and children, is the focus of the Whitney Plantation according to John Cummings the man who bought the plantation and developed it into a museum. He envisioned it as “an open book up under the sky, that people can come here and see (80).” It is a place Smith says that is trying to retell a story that has been told incorrectly.

At first I was confused why Clint Smith included Angola Prison, also in Louisiana, among these other tourist destinations in How the Word Is Passed, until he explained that the largest maximum security prison in the country was once the site of a plantation. It was no coincidence that the formerly enslaved became the newly incarcerated through unfair laws and loopholes. Of course this transition was not one highlighted on the tour or featured in the Angola gift shop. “If in Germany today there were a prison built on top of a former concentration camp, and that prison disproportionately incarcerated Jewish people, it would rightly provoke outrage throughout the world…And yet in the United States such collective outrage at this plantation-turned-prison-is relatively muted (101).” Unlike Monticello and the Whitney Plantation, Angola is still in use and the inequality of the carceral system still very much alive in America.

Obviously, the topics Clint Smith touches on in How the Word Is Passed are heavy to say the least. But with his thoughtful first-person narration, his ability to distill truth from tragedy, and his poetic phrasing Smith’s book is accessible and engaging. I could have easily devoured this book in a day or two, but I intentionally took my time reading it. I wanted to linger over each location and really sit with the challenges Smith was presenting to me as a white person and history lover. I’ve been to Blandford Cemetery in Petersburg, Virginia and seen the Tiffany windows erected at the church there by the Ladies Memorial Association. I remember being secretly pleased that Virginia’s window featured the disciple John. Once I might have agreed with the docent whom Smith interviews who says that preservation is different than celebration, but now I’m not so sure. According to How the Word Is Passed, a 2018 report by Smithsonian Magazine revealed that over the preceding decade at least forty million dollars of taxpayer money had been spent preserving Confederate monuments. All that money to preserve a myth and perpetuate white nationalism that could have gone to schools, summer programs, reparations, and other more worthy causes.

When Smith arrives in Galveston, Texas site of the original Juneteenth celebration, the book pivots from historical sites telling their chosen narratives about slavery to African Americans taking the crafting of this narrative into their own hands. Every year Galveston hosts a Juneteenth celebration including a re-enactment of the 1865 proclamation announcing the end of slavery. The original public celebration of Juneteenth in the late 1800s was a rebuke to the Lost Cause narrative spreading through the south. It was also a way to instill in public memory the truth when the powers that be insisted on a lie. The organizers of the Juneteenth celebration that Smith attends are intentional about involving young people. They believe that “when you give young people the tools to make sense of their history, you are giving them the tools to make sense of themselves, thus fundamentally changing how they navigate the world (199).” This is of course what those calling for the banning of books and the teaching of Black history fear most: not just the truth of the past that institutions have tried to obscure, but the impact of that truth on those whom institutions have tried to hold down.

In New York City, Clint Smith joins a walking tour on the history of slavery and the Underground Railroad. Like Angola prison, Monticello, and most of America the narrative of New York City is also a complex one not easily divided into “good guys” and “bad guys.” Once home to the second largest slave market in the United States, the city’s economy was so tied to slavery that its mayor suggested they join the south in seceding from the Union in 1861. Many banks that are still in business today made their fortunes by accepting enslaved people as collateral for loans, but you won’t find that information on any of the Wall Street buildings now occupying the site of the old slave market pavilion.

Having traversed the eastern United States, Clint Smith expands his look at the history of slavery by returning to the source. Goree Island in Senegal was a port for slave trafficking from the sixteenth century until 1848. There, the House of Slaves, once the residence of a wealthy trader, has been preserved as a symbol by the Senegalese government and a “place where we can remember and reckon with and learn about and think about the history of slavery (252).” Such could be Smith’s prescription for all the places he visits in How the Word Is Passed. But in reckoning with the history of slavery in these places America must also grapple with the myths and nostalgia festooning them like so much patriotic bunting.

The book ends with Smith in conversation with his maternal grandfather and paternal grandmother about their own experiences as the grandchildren of persons born into slavery. From their conversations and his travels and research, he decides it is not enough to have only a “patchwork of places that are honest about their history while the being surrounded by other places that undermine it (289).” What the United States needs is a broader campaign to confront the story of slavery and its impact on the nation. A campaign conducted by scholars and public historians, teachers, museums, students, and the descendants of those who were enslaved. The need for such an endeavor grows daily as politicians race to ban books and obstruct the teaching of Black history.

During my reading of How the Word is Passed our family left Canada and moved to East Tennessee. Five years of living in Canada had given me the opportunity to view America from the outside and I returned to my native country feeling like an outsider. I found myself identifying with Smith, himself ever the cultural outsider, at various historical sites and also at the end of the book as he examines his own life for “gaps” in his history. His gaps are the result of being a Black man in America whose lineage is lost somewhere in the Middle Passage. The gaps in my family’s story are more like the tours at Monticello, some we take and some we don’t because the truth in those tours makes us uncomfortable. What stories had not been handed down in my family and why? How complicit were my ancestors when it came to slavery in America? I was about to find out.

A Review and a Reckoning Part 2. I uncover my own family’s secret plantation past and grapple with the discovery in light of Clint Smith’s book.