Ah, the colors of fall. Orange, red, gold, russet, and … pink. Yep. October is National Breast Cancer Awareness Month and, if you have breasts, chances are your social media timeline is full of pink ribbons reminding you to get a mammogram. This low dose x-ray can spot cancers, benign tumors, and cysts in breast tissue even before a potentially problematic lump has formed. Since 1989, over half a million deaths have been prevented because of early detection and advances in the treatment of breast cancer.[1] While medical experts agree a mammogram is the best way to detect early-stage cancer, at what age a person should begin receiving mammograms is up for debate.

The American Cancer Society recommends mammograms yearly for women ages 45-54[2] (earlier if a doctor thinks it’s necessary), while the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American College of OBGYNs prefer to start screening patients for breast cancer at age 40. Across the border in Canada, unless there are symptoms of breast cancer or a patient carries the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, mammograms aren’t provided to patients until age 50. The United States Preventative Services Task Force’s guidelines also delay screenings until age 50, which can be problematic for African American women. According to NPR almost one third of the African American women who get breast cancer are in their forties.

For several years I existed in mammogram limbo, stuck between an insurance company that wouldn’t pay for a mammogram at 40 and the Ontario Healthcare Plan where coverage for mammograms didn’t kick in until 50. Even with a family history of breast cancer (my mother, aunt, and grandmother all had it), neither insurance provider deemed my risk not serious enough to make me eligible for an earlier screening. So, it was at age 46, after making the move back to the US, that I prepared for my first mammogram.

I wore my “What Would Dolly Do?” t-shirt featuring the likeness of Dolly Parton, which seemed fitting, but other than that, the procedure was unremarkable. After a few rounds of “Bend… Now don’t breathe!” from the radiologist, I was dressed once more in my Dolly t-shirt and off for a celebratory coffee and gluten free cinnamon roll. I hadn’t been home long when my cellphone rang with a call from the doctor’s office. It turns out my breasts are “dense,” and the radiologist needs to have another look with an additional mammogram and an ultrasound.

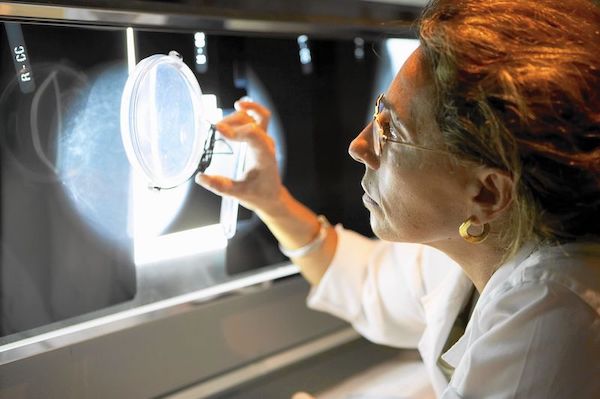

All breasts are a combination of dense tissue and fatty tissue, but how much of each isn’t something that can be detected visually or through a self-exam. That’s where the mammogram comes in. On a mammogram, fatty tissue allows x-rays to pass through and appears black, and x-ray blocking dense tissue appears as white or light gray. What else blocks x-rays and also shows up as a white blob on a mammogram? A cancerous tumor, or any mass for that matter. And because 50% of women in their forties have dense breasts, along with 60% of transgender persons, I’m not the only one receiving a call from the doctor with tidings of “inconclusive mammogram[3].”

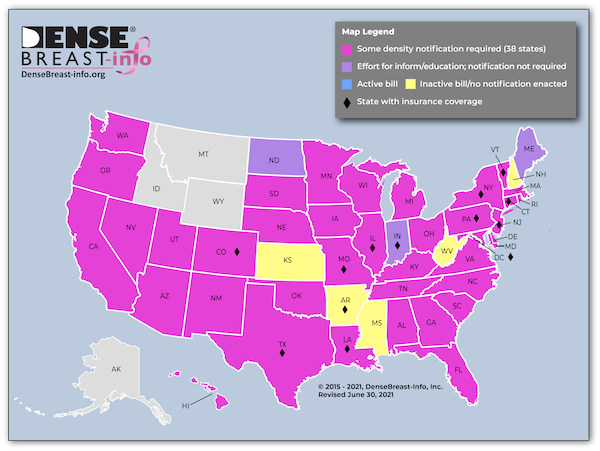

You might think my first concern was the possibility of cancer, but being back in the US, my first thought was the cost. “Are these extra tests covered by my insurance?” The Affordable Care Act ensures that individuals receive free screening mammograms, but diagnostic mammograms and other diagnostic tools like ultrasounds are not included in this mandate, even though for half the women under 50 that initial screening is incomplete. Thirty-eight states have mandated that people with dense breasts receive a letter notifying them of this fact[4] because their likelihood of having breast cancer is four to six times higher. Yet only twelve states have laws requiring insurance companies to fully cover additional diagnostic tests, and even those laws may not apply to all insurance policies in the state or to residents with national insurance providers. In states like New York, a patient’s doctor must make the case to the insurance company that an ultrasound is indeed necessary. That request could still be denied and the patient forced to appeal the company’s ruling.

In 2019, Susan Komen commissioned a study to better understand the wide-ranging costs of diagnostic breast imaging and the insurance issues patients have encountered. “I was scheduled for a breast MRI in October, but when I found out that I would first have to meet my $500 deductible and then still have to pay even more (insurance will only cover 80% until I meet the $2500 max out of pocket), I ended up cancelling that procedure. I still haven’t gotten it because I can’t afford it right now.” This women’s story was like many who were interviewed for the study. Researchers found patients often cancelled or postponed diagnostic follow ups because the cost, if they could even discover this amount. Often a hospital or imaging center cannot (or do not) tell patients the total cost of procedures. Radiologists, other personnel, and unnamed factors are often unaccounted for in preliminary estimates and these unknowns impact patient decision making. If you’re income is limited, unknown expenses are a risk you literally can’t afford to take.

“It’s a Business…and if patients get cancer then the insurance company is guaranteed a steady stream of income at least for the next couple of years. it’s terrible, but that’s how it’s set up.”

Understanding Cost & Coverage Issues with Diagnostic Breast Imaging, a report for the Susan G Komen Foundation

Insurance companies are aware of the situation and the danger it poses to those needing additional testing. When researchers interviewed healthcare and insurance professionals, cost was the primary reason patients did not follow up with diagnostic testing after their initial screening mammogram. But don’t be deceived into thinking insurance companies intend to do anything about it. Insurance companies are counting on the fact that shoddy coverage and high costs force patients and employers to switch providers. So, an inconclusive or concerning mammogram might not be the problem for that particular provider for long. One professional interviewed offered this assessment, “It’s a business…and if patients get cancer then the insurance company is guaranteed a steady stream of income at least for the next couple of years. It’s terrible, but that’s how it’s set up.”[5]

Here in Tennessee, I’m awaiting the letter telling me “You have dense breasts and are more prone to breast cancer. Your insurance company doesn’t have to cover any diagnostic testing, so good luck with that.” Our situation isn’t great, but I will be okay. We are in a transition in ministry and currently unemployed, but we have some money set aside and family willing and able to chip in if testing gets expensive. But too many people who need additional tests don’t have such resources to draw upon. Low-income workers and minorities, who are generally paid less, tend to have more limited access to hospitals and diagnostic imaging facilities. White women have a greater incidence of breast cancer; but African American women are twice as likely to die from breast cancer due in part to delays in follow up diagnostic testing.[6]

Transgender patients and persons who are incarcerated face additional hurdles when it comes to diagnostic testing. The Bureau of Prisons only requires detention facilities provide mammograms to inmates who are over the age of 50 every 2 years unless a physician determines otherwise.[7] But, as we’ve seen, a physician cannot accurately determine breast tissue density and other risk factors through a physical exam or even a single mammogram, and for women of color, 50 may be too late.

While the ACA does not discriminate in screening coverage, finding medical care as a transgender person can be difficult. Many diagnostic imaging facilities are designed with cisgender women in mind. They do not include waiting areas for transgender individuals, and this becomes another barrier to medical care. The US system of employer-based health insurance coupled with high rates of unemployment in the transgender community means that many transgender people are uninsured. They are further discriminated against when they are unable to access healthcare through a partner or spouse’s insurance plan.[8] Considering that transgender individuals are more likely to have dense breast tissue than the general population, their need for additional testing is also greater.

Currently, a bill in the Senate – the Access to Breast Cancer Diagnosis Act, introduced by U.S. Senators Roy Blunt (Mo.) and Jeanne Shaheen (N.H.) – hopes to make breast cancer diagnostic tests more affordable and accessible. This bipartisan bill will require insurance companies to cover diagnostic testing for breast cancer just as they currently cover screenings for breast cancer. Considering 10% of women will receive a referral for additional testing, this legislation could go a long way in helping save lives since early detection is key in fighting cancer. The sooner passed the better, especially since many have already delayed testing due to COVID.[9]

As for me, I have a follow up diagnostic mammogram and ultrasound already scheduled. I’ve already spoken to my insurance company, or at least to someone who answered their phone number. He seemed to know as little as I did about my coverage. As far as shopping around for prices, I’ve already checked out a “discount imaging” website for a place in Knoxville. I’m sure it’s value menu of radiology services is fine, but is diagnosing cancer something you really want to do on the cheap? I did find a “menu” for the center my doctor recommended, but it doesn’t include any of those extra expenses like the radiologist or technician that can really inflate the price.

The more I read and research about breast cancer, the conflicting information, the complete lack of information, the loopholes in coverage and blackholes of funding, and the arbitrary and the deliberate inequalities in the system, the more I am convinced that this dense, disorienting morass that we call healthcare serves no one’s interests save the insurance companies and their shareholders- and I don’t need any additional diagnostic tests to tell me that.

[1] https://www.breastcancer.org/research-news/mammos-and-tx-advances-save-hundreds-of-thousands

[2] https://www.cancer.org/healthy/find-cancer-early/american-cancer-society-guidelines-for-the-early-detection-of-cancer.html

[3] https://densebreast-info.org/

[4] https://densebreast-info.org/legislative-information/state-legislation-map/

[5] https://www.komen.org/uploadedFiles/_Komen/Content/What_We_Do/Advocacy/komen-understanding-cost-coverage-with-dbi-final-report.pdf

[6] https://www.komen.org/wp-content/uploads/A-Perfect-Storm-FINAL-12-13-16.pdf

[7] https://www.bop.gov/resources/pdfs/phc.pdf

[8] https://www.ajronline.org/doi/full/10.2214/AJR.13.10810

[9] https://www.blunt.senate.gov/news/in-the-news/lawmakers-introduce-bill-to-make-breast-cancer-diagnostic-tests-more-accessible-and-affordable