January 27 is the day we like to say our collie, Skye, earned her “Lassie card.” I was in the kitchen preparing our daughters’ school lunches when I heard Skye barking outside – really barking, much louder than her usual “Scram, squirrel,” bark. She didn’t stop and it sounded like she was really close to the house, which was odd because my wife, Kristen, had just left to take her on her morning walk. Skye was so persistent that I stopped what I was doing and went out the back door to investigate. There I found Kristen and Skye (dragging her leash behind her) coming around the side of the house, though Kristen was struggling to walk.

Kristen had slipped on a patch of black ice – a perennial winter hazard here in Ontario – and broken her right wrist. I could tell it was bad. She was in pain and going into shock. I helped her into the house, called a friend from church, and started making the surreal preparations to get our girls to school and get my wife to the hospital.

I caught up with Kristen later that morning in the emergency waiting room. The area was aptly named. Seats were hard to come by, and there was a lot of waiting – first for x-rays, then for post x-ray consultation, then for a doctor to set the bone. It was nearing supper time by the time we got home.

The next several weeks were a blur. My mother-in-law came to stay with us for a month, since Kristen needed help with the everyday tasks we all take for granted when our wrists work properly. She also experienced complications with the break. The cast began pinching a nerve and had to be replaced. Follow-up x-rays revealed the bone wasn’t setting the way the doctor intended and would require surgery in order to heal properly. Post-op doctor visits and physical therapy followed the operation along with the onset of COVID and all the worries that normally come with a serious injury. Of all the things we had to worry about, however, how we would pay for Kristen’s expert care wasn’t one of them. Between the time she fell in late January and the time she got her final cast off in late March, our out-of-pocket medical expenses came to a grand total of $89. ($39 of that was for hospital parking). No premiums. No co-pays. No deductibles. Each time she visited the hospital or the doctor’s office, Kristen would scan her OHIP (Ontario Health Insurance Plan) card and that was that.

This has been our experience of the Canadian healthcare system in action, a system both revered and reviled in the United States: revered by struggling patients who make pilgrimages to Canada to purchase affordable insulin and reviled by conservative pundits who denigrate it as a socialist nightmare rife with rationing, shortages, and delays so long that people regularly die waiting to access the care they need.

It is true – waits do happen in Canada, and in more places than the emergency room, but not always. Kristen’s wrist surgery took place two weeks after her doctor deemed it necessary. However, a friend recently told me about a relation of hers in Nova Scotia who had to wait months for a similar operation. In the interest of fairness, it should be noted that our experience of Canadian healthcare has unfolded in Toronto, Canada’s largest city and home to many of its best hospitals and medical schools. Every type of medical care a person might need is available here, and all you need to access it is a health card and the patience to deal with traffic. That isn’t the case everywhere, especially in rural parts of the country. The waits can be frustrating. Yet, criticism of wait times within the Canadian healthcare system is often levelled as if waits are not a feature of the US system. In fact, while studies show that average wait times are longer north of the border, US wait times still tend to be lengthy: 40 minutes to an hour on average in the emergency room and 24 days or more to schedule a first appointment with a doctor.

It should also be noted that one factor driving longer wait times in Canada is that a higher percentage of the Canadian population has ready access to the system.[1] If you are a legal resident of a Canadian province, you have healthcare coverage through the Canadian Medical Care Act – coverage that removes the cost barriers from essential medical services. Meanwhile, in the United States prior to COVID, an estimated 8.5% of Americans (or more than 27 million people) did not have health insurance of any kind.[2] That lack of coverage reduces demand by deterring the uninsured from seeking care unless it is absolutely necessary. Furthermore, the very nature of the private, for-profit US health insurance market discourages use of the medical system. Even America’s insured delay seeking non-urgent medical care at times because of high deductibles that result in high up-front costs.

“the very nature of the private, for-profit US health insurance market discourages use of the medical system”

Having access to care based on one’s need rather than one’s ability to pay makes a difference. Infant mortality is significantly lower in Canada and life expectancy is generally higher. In my observations, quality of life also tends to be better. The seniors in my church here in Toronto are, on the whole, healthier than the seniors of churches I’ve pastored in the United States. Access to healthcare cannot fully account for this difference (socio-economic status, lifestyle choices, genetics, and other factors play a role, too); however, these Canadian seniors are of the generation that has had access to affordable healthcare virtually their entire lives. There is a cumulative benefit to that kind of access. Health problems are identified and treated before they become more serious, and patients and their families are spared the emotional and financial burden of medical debt that impairs other aspects of life.

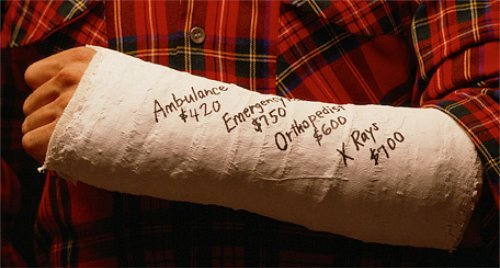

Many Americans are suffocating under the weight of their medical expenses. One recent study found that twenty-eight percent (28%) of working American adults owe $10,000 or more in medical bills. Another study concluded that 137 million Americans (roughly one third of the US population) faced financial hardship at some point in 2019 connected to their medical bills. The cost of medical care is the number one reason Americans cite for dipping into their retirement savings early, and sixty-six percent (66% – two thirds!) of all personal bankruptcies in the US are related to medical debt.

Thankfully, my wife and I have never had to contemplate bankruptcy. But before moving to Canada, medical expenses most definitely had a negative impact on our personal finances – and we can count ourselves among the privileged who have always had health insurance, first as dependants on our parents’ plans and then through our employers.[3] Nevertheless, our ability to afford our deductibles routinely influenced our healthcare decisions. Medical expenses weighed on our household budget. When our twin daughters were born in 2008, our share of the hospital bill was over $4,000, even though the girls were perfectly healthy and did not require any special care prior to discharge. When the invoice arrived in the mail, I thought it was a mistake! But there was no mistake. The insurance claim had gone through and this sum was our share of the cost plus our unmet deductible. When I tell this story to friends here in Toronto, their mouths literally drop open. Fortunately, we were able to come up with the money; but so many people can’t. Few Americans can truly afford all of the medical care they need – and it isn’t a secret. When my father-in-law posted the news of Kristen’s impending wrist surgery on Facebook, asking for prayer, a notice popped up on his timeline asking if he’d like to start a GoFundMe campaign!

Why does the richest nation on earth tolerate, much less accept, a healthcare system that yields these results? Admittedly, a universal, single-payer system such as Canada’s isn’t perfect. Not everything is covered, and not everyone has equal access to the benefits of that coverage. There are waits and other frustrations. Taxes are higher to pay for it. But the major health concerns we all fear are covered, and you know it will be there when you need it. Life in Canada, for all Canadians, is better and less anxious because of it.

Universal health care is better for individuals, for congregations, and for businesses. The cost that my Toronto church incurs to provide me and other staff with supplemental insurance is a fraction of what it cost my US congregations to provide me and my family with a comprehensive policy. That holds true across the board for other businesses, organizations, and enterprises here in Canada. And one of best things about OHIP is that it’s portable. It goes with us wherever we might live and for whomever we might work in the province of Ontario. If I wanted to blaze a trail as an entrepreneur, it would go with me into that, too. I wouldn’t have to go without health coverage – or ask my family or my employees to go without it – while I was trying to get a new venture off the ground. No one in Canada goes bankrupt because they get sick, and you never have to do battle with an insurance company that weighs shareholder profits against your healthcare needs.

“No one in Canada goes bankrupt because they get sick, and you never have to do battle with an insurance company that weighs shareholder profits against your healthcare needs.”

Before moving to Canada, we had to pay hundreds of dollars out of pocket for medications because our insurance wouldn’t cover the name brand. The fact that Kristen is allergic to an inactive ingredient in the generic didn’t warrant an exemption. It was too costly for the insurance company, and that was the deciding factor. Worse, a woman in the first church I pastored, whom I’ll call “Jessica,” needed a CyberKnife procedure to treat a tumor growing around her ocular nerve. Standard radiation likely would have left her blind. No matter. Her insurance company refused to cover the CyberKnife because it was too expensive. Our church had to join with other community organizations and her friends and family to raise the money for her to have the CyberKnife – a treatment she deserved to have because it was the best available treatment for her disease and for her well-being. In contrast to “Jessica’s” experience, a member of my Toronto congregation has had not one but two CyberKnife treatments for brain cancer. OHIP covered both without question because it is the best available treatment for her. Isn’t that how a healthcare should work?

A system that offers access to that kind of treatment could exist in the US. The only reason it doesn’t is because the American people haven’t demanded it. We complain about insurance companies and feel the squeeze of medical debt and increasing costs for insurance premiums, co-pays, and deductibles. Rarely, however, do we take those complaints with us into the streets or even into the voting booth. We seem resigned that the system we have is the system we have. But it doesn’t have to be. Living in Canada has proved to me beyond a shadow of a doubt that US Healthcare could be effectively organized and delivered according to a different set of priorities and principles.

Canada’s current healthcare system hasn’t always been. Prior to the 1966 Medical Care Act, Canadian healthcare was privately funded and privately delivered, much as it is in the United States today.[4] The system changed because there was a push for it to change. That change began in one province (Saskatchewan in 1947) and expanded from there as the benefits became clear and as the Canadian people decided that access to necessary health care ought to be available to everyone because that’s the kind of society they wanted to live in. Canada voted for the system to change, and that’s how the system will change in the United States, too, if it ever does. When the American people summon the political will for it to happen, it will happen.

So, as you go to the polls this Fall, ask yourself what kind of American society you want to live in. One where access to medical care is a matter of basic human decency and dignity? Or one where access to medical care is a perk reserved for those “worthy” of it because they can afford it? We do have a choice.

[1] Other industrialized countries with universal healthcare systems tend to have shorter wait times than Canada, so long waits are not an inevitable byproduct of universal healthcare, as is often suggested in.

[2] Since the onset of the pandemic and the accompanying job loss, the number of uninsured has increased.

[3] For a few months in 2009, my family and I had a private insurance plan while I was between jobs but our coverage never lapsed.

[4] Canadian healthcare is still, by and large, privately delivered.