While planning my daughters’ homeschool history lessons I stumbled across Wheatlands Plantation about an hour away from where we’ve been living in Tennessee. Not much remained of the original property and only the 1825 house and a few outbuildings were still standing. However, it wasn’t the architecture that caught my eye, it was the name of the original owner, “Timothy Chandler.” I knew that name. Timothy Chandler was a Revolutionary War veteran who established Wheatlands as a family farm in 1791, but most importantly he was the great grandfather of my great-great-great grandfather William C. Chandler.

I was shocked to say the least. I had never heard of Wheatlands or any ties to any plantation in our family and neither had my mother whom we regard as the family historian. Grandpa Chandler’s exploits were legendary, but none of the stories handed down about him included a great uncle who owned a plantation. In fact my ancestor, William Chandler enlisted on the Union side in the Civil War while his Confederate great uncle, John Chandler, owner of Wheatlands, made a hasty marriage to a Union sympathizer at age 73 and then hid out for the duration while she ran the plantation. Union soldiers occupied the house and property but left both unharmed, so I suppose his plan worked.

By W.C. Chandler’s time in 1850, Wheatlands had become one of the largest plantations in the county. Measuring 4,600 acres the farm produced oats, sweet potatoes, hogs, cattle, wool, and distilled 18,000 gallons of whiskey a year from its immense wheat crop. Wheatlands was second only to George Washington’s Mount Vernon in Virginia in whiskey production. Obviously, the Chandlers weren’t doing this on their own. Family records indicate 188 enslaved persons were laboring at Wheatlands at the close of the Civil War and the University of Tennessee archeology department has located 70 of their graves on the property along with the footprint of six slave cabins.

The plantation stayed in the family for another hundred years and then passed through the hands of private individuals until it was bought by an investor in 2006 who hired two house flippers in 2011 with an eye to restoring Wheatlands to its former glory as a site for weddings, tours, and events. A little poking around on the internet shows they were successful in restoring the house and filling it with period furniture. They even held a few events and hosted the local historical society meetings but when that wasn’t enough to keep the plantation running the team began promoting the property on the paranormal circuit as a locale for ghost hunters. Wheatlands had gone from exploiting the enslaved to exploiting their ghosts. In the end, the cost of restoring the plantation to the level of a mini-Monticello outpaced what the investors could supply and the house went back on the market.

Having read Clint Smith’s How the Word Is Passed, I began to wonder “what if?” What if I had inherited this antebellum plantation? Would I have done things differently than those developers with their dream of a “Gone with the Wind” wedding venue and microbrewery? I would like to think so. I would also like to think that I’d be honest about the story of Wheatlands. The last heir to live in the house wrote that her ancestor was “known as a good master who didn’t believe in separating families,” and after the war it’s said he paid those formerly enslaved to stay on and work at Wheatlands. But “good master” is itself an oxymoron and sharecropping isn’t the same as freedom. I decided to follow Clint Smith’s lead and journey to Wheatlands Plantation to see it for myself.

“But “good master” is itself an oxymoron and sharecropping isn’t the same as freedom.”

If I hadn’t known it was Wheatlands, I would have thought it was just another old house. No longer 4,600 acres, the property has dwindled to a little over one with paved roads running in front of and alongside the house. No one was home, not even the ghosts. A sign out front marked it as a site on the National Registry of Historic Places but gave no other information other than the year the house was built. Todd and I parked in the gravel lot of the storage unit across the road next to the house and made our way over to investigate. Not wanting to trespass, we confined our exploration to the perimeter of the property along a weedy ditch interspersed with dirt driveways. I could see several of the old buildings huddled together next to the main house. It appeared that the portions of the property containing the cemetery, Cherokee burial mound and barns had been sold separately when the developers could not find a buyer for the house and all seven acres.

Exploiting the graves of enslaved and indigenous persons for profit is horrific. But I would also hate to see those sites become overgrown and lost to history now that they’ve been sold off. Organizations like the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation’s (ACHP) Office of Native American Affairs and The Slave Dwelling Project have means to preserve these sites in a more respectful way, but it’s unclear if the new owners will use them. Separating the cemetery from the house also removes the historical context and consequences. For so long slavery was not a part of the Wheatlands Plantation story and now with the division of the property it’s been completely cut off from the narrative. If I owned Wheatlands and gave it a historical focus, one more in line with Whitney Plantation’s approach in How the Word Is Passed, would the Sevierville plantation have been sustainable?

I’m not naïve enough to think my ancestors were innocent when it comes to slavery. Even those who didn’t own enslaved persons outright benefitted from the slave trade and from an economy built on forced labor. My family certainly benefitted from the status that being white in the world of the segregated south afforded them. But up until the discovery of Wheatlands Plantation, my ancestors’ involvement with the slave trade had been unremarkable. I had encountered the mention of one or two enslaved persons in an eighteenth century will on my paternal grandmother’s side and vaguely assumed that those long-ago Jamestown Chandlers must have had some involvement as well, but I’d never seen anything concrete about it.

Most of what I discovered was in the contents of John C. Chandler’s will dated December 1861. He suspected the war was coming and wanted to get things in order. In the first two pages of the will, John Chandler disposes of his various tracts of land and then on the third page just as dispassionately he begins disposing of his “Negroes.” First to go was “a Negro woman named Elvja and her nine children. To wit: Malinda, Harriet, Montgomery, Daniel, William, Riley, Calvin, Caroline, and Elizabeth which Negroes I value at twelve hundred dollars because I purchased the Negro woman and her then older children (the rest having since been born) at that price for my son W. Chandler, and the said family of Negroes having been raised by the family of W. Chandler.” Next he orders the remaining slaves be divided into five lots for his remaining heirs but he does request that they be divided by family “as near as possible.” It’s this last bit that earned John C the “good master” title in the advertisements about Wheatlands Plantation.

“And while I expected to find slaves enumerated with land and livestock in some sort of accounting, what I did not expect were the names. Seeing Elvja’s name and the names of her children gave form to what until then had been mere phantoms.”

Scrolling through this portion of John C. Chandler’s will, it’s hard to say which element was the most disturbing. Certainly describing people as having been “raised” like chickens, assigning them a price tag, and then jumbling them into lots with only the slightest regard to families was cold and calculating. And while I expected to find slaves enumerated with land and livestock in some sort of accounting, what I did not expect were the names. Seeing Elvja’s name and the names of her children gave form to what until then had been mere phantoms. And some of the names were ones common in the Chandler family like “William”, the name of John’s own son and my ancestor W.C. his great nephew, and “Calvin” the name of W.C.’s father. It made me wonder if this was merely convention or something more. I was in Virginia when the news about Sally Hemmings and Thomas Jefferson hit the old south like a grenade at a garden party. If anything, Clint Smith undersells the hysteria it caused in the Commonwealth in How the Word Is Passed. What would a DNA test reveal about our own family tree? The possibility that John C. was doing this to his own children or grandchildren made the will’s provisions even more repulsive. Constructing and narrating the history of Wheatlands Plantation was becoming ever more difficult.

It appears the owners did try a Civil War Living History Event with Abraham Lincoln, Mary Todd Lincoln and Robert E. Lee look-a-likes, as well as a re-enactment of a skirmish complete with medical tent. But like much of what passes for history at these places it was probably little more than Cos-Play Confederacy designed to re-enforce the Lost Cause narrative and benevolent master myth. There’s a reason places like Monticello and Blandford Cemetery are “slavery lite.” It’s the same reason the preservationists that invested in Wheatlands struggled to sell a wedding venue featuring a slave cemetery and eventually had to go with the ghosts. America runs on consumerism and comfort. People don’t want to spend their time and money on things that make them uncomfortable including their history.

Several of the sites that Clint Smith visited in How the Word Is Passed have already begun the process of atoning for the past in various ways. Monticello gives any Black descendant of those once enslaved there a one time higher education scholarship of $5000. Perhaps it is not enough, but where Monticello leads, others are likely to follow. The Whitney Plantation is already known for prioritizing the narrative of the enslaved as well as community outreach, so it is no surprise they are taking a more systemic approach to reparations in the community. Their Descendants Project helps the descendants of people enslaved in the area by advocating for Black owned land. In the future they hope to create a land trust for descendants, organize protests, and establish standards for how other plantations might collaborate with their own descendants.

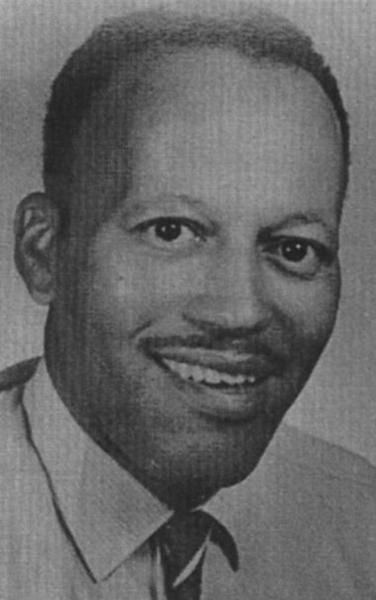

What about the descendants of those enslaved at Wheatlands? I am ashamed to say it wasn’t the first thing on my mind in my mythical ownership of the plantation until I read John Chandler’s original will, and I doubt it crossed the mind of the actual owners at all. By the time John Chandler finally died in 1875 in a new will he left his former slaves, who were still laboring there, a portion of the property that became known as Chandler Gap. Many of them took the last name Chandler and settled in the area which became the nexus of the small Black community in Sevierville. James Walter Chandler, whose great-grandfather, Louis Lincoln Chandler had been born into slavery on Wheatlands Plantation, became the first African American teacher to teach at an integrated school in Sevier County. James Chandler had grown up on a farm in Chandler Gap and later earned a master’s degree in Education at the University of Tennessee before being chosen to teach seventh grade at the all-white Sevierville Elementary School in 1965.

Like the rest of the United States, Sevierville has a history of racism and inequality the origins of which are deeply rooted in the slavery that existed at places like Wheatlands. It’s a national problem needing national solutions for reparations on a larger scale that what private organizations can accomplish. But if Americans are reluctant to attend a tour about slavery, it will be difficult to achieve buy-in for anything like reparations from the U.S. government.

“But if Americans are reluctant to attend a tour about slavery, it will be difficult to achieve buy-in for anything like reparations from the U.S. government.”

As a former educator and someone with a PhD in Education from Harvard University, it’s not unexpected that Clint Smith would call for a national program to educate America on the history of slavery, one engaging the talents of scholars, museums, teachers, and community memory keepers. I’m inclined to agree with him, especially when it comes to the role of public schools in educating children about the truths of slavery. But in the year since his book was published politicians and white parents have become more extreme in trying to prevent children from being exposed to Black History and the historical realities of racism.

Williamson County Tennessee’s Education Commission heard arguments from the conservative parent group, Moms for Liberty, in favor of banning the children’s book Ruby Bridges Goes to School. The book was written by Ruby Bridges herself about her experience integrating her elementary school in New Orleans as a six-year-old child. The group’s leader complained that the book included documentary photographs of angry white people protesting Bridges and that this inclusion was “harsh.” She also did not like the fact that there was no “redemption” at the end of the story for the white people. I would argue that the story of that redemption has yet to be written, but it’s not too late.

I missed my chance to purchase Wheatlands Plantation and enact any of my “what if” plans. Wheatlands was put up for sale again and eventually sold to a family in 2019. On our visit we saw, sitting not far from the main house, a jungle gym with swings and a slide. It’s nice to think someone might see it as “home” rather than merely as an investment opportunity. And hopefully the children who enjoy that swing set will have the opportunity to learn the full history of their home both the good and the bad, because they will need both to make this country better.

Part 1 of this series is a look at Clint Smith’s book How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America