This is the second in a series of articles examining the parallels between the history of the Baptist church in America and the history of Old-Time String Band Music. Why it matters, here.

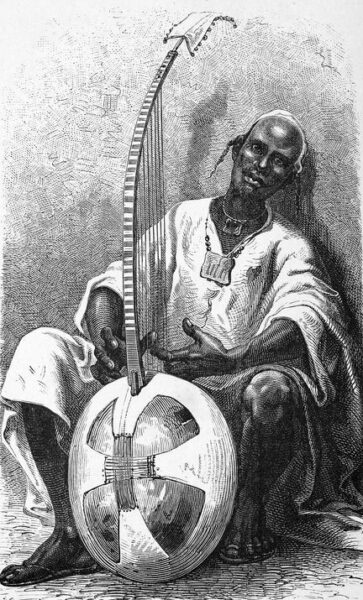

A hereditary class of musician storytellers in West Africa known as griot, performed their recitations of tribal history accompanied by stringed instruments made of gourds covered with animal skins. The various iterations of this instrument, combined in the New World to become the banjo (Marks). That the banjo’s African antecedents were associated with storytelling and preserving generational memory is sadly ironic because slavery, appropriation, revisionism and racism have obfuscated the banjo’s own story. The same also happens to be true of Baptist history and heritage relating to slavery, appropriation, revisionism, and mission.

I love African music, I love Country music, and I also love the historic Baptist principals and values of freedom and democracy. It’s tempting to simply revel in the beauty of all these and ignore the ugly sides of the banjos incorporation into country music. To applaud the Baptist faith’s forward thinking on religious and soul freedom, and skip the next century entirely. But ignoring the ugly side never makes it disappear. On the contrary, when Baptists did just that in the 1800s, it set the denomination on a course from which it has yet to recover.

Baptists had backed the winning side in the Revolutionary War, and with the Constitution’s guarantee of freedom to worship, paired with the revivals of the Second Great Awakening, the denomination grew to become the largest in the country by 1800. However, a foundation of freedom made it difficult to build theological consensus across the denomination. When to worship, how to worship, and whether or not to do mission work were questions dividing the growing denomination. But it would be the question of slavery that would cause the greatest division (McBeth, 343-344).

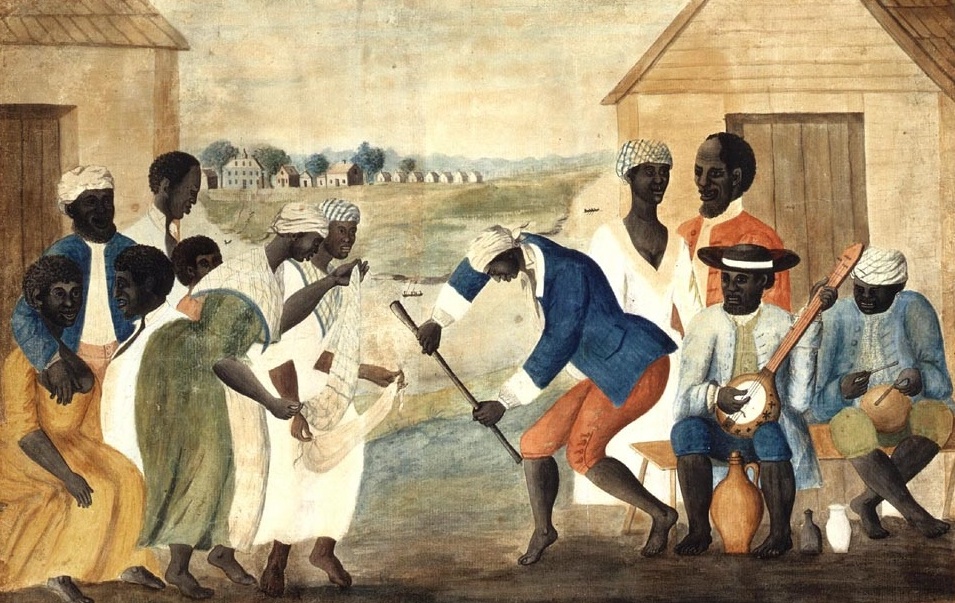

The banjo spread through the colonies simultaneously with the spread of slavery[1]. Mention of the banjo crops up in a 1755 advertisement for a runaway slave who “plays exceedingly well on the Banjar.” A year later, an “African Frolic” was held n Newport, Rhode Island, featuring a banjo and fiddle duet performed by two black musicians (Giddens, 6). When Governor Thomas Jefferson wrote his 1781 Notes on the State of Virginia, he included a description of the music of his African slaves and “their instrument, the Banjar, which they brought hither from Africa, and which is the original of the guitar” (Epstein, 10, 34). Twenty years later, when Jefferson was president, the banjo had become as commonplace in the new United States, as Baptist churches.

In 1785 the Baptist General Committee of Virginia opposed slavery declaring it “contrary to the word of God,” and most Baptists shared that view (Leonard, 185). Baptist mover and shaker John Leland, said freedom was the “birth-right blessing” given to all, including slaves (Gourley). The freedoms espoused in the Baptist tradition appealed to enslaved African-Americans looking for a way to practice their new found Christian faith, especially the freedom of the local church to exist as an independent body (Leonard, 264).

Because Baptist ecclesiology gives priority of place to the individual conscience, any Baptists who can get along can eventually form a church. That church is then a completely autonomous body. Each church can decide its own leadership, worship style, and membership requirements without seeking permission from any other ecclesial body. Forming Baptist churches became one important way that black Christians could create political, social, and economic standing for themselves in the south. Historic examples of this are the First African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia and the First Baptist Church in Petersburg, VA both of which were founded and led by slaves (Leonard, 266 and Luqman-Dawson, 35). The Petersburg congregation was the first Baptist church of any color to be established in that city.

The Baptists and the banjo made their way from Tidewater, Virginia through the Blue Ridge Mountains to Grayson County, later Galax, Virginia in the first decade of the 1800s. The Scotch-Irish with their brisk fiddling style had been settling in fits and stops around New River since the mid-1700s (Emmick, 32)[2]. Appalachia was not a “slave society,” but rather a “society with slaves”[3] where a few farmers had a slave or two who worked alongside them in the field or at the mill. Even with fewer slaves than the deep south, there was plenty of racism to go around, and many poor whites, who comprised most of the Baptist church rolls, derived a twisted social satisfaction in having slaves to look down on and torment (Turnmire, 3). Because the slave population was scattered, there wasn’t a looming threat of rebellion and this lack of fear actually facilitated musical exchange (Inscoe, 29). The close proximity of black and white Virginians is reflected in the tight pairing of the banjo and fiddle native to the area (Reiner, 83). The thumping clawhammer style of banjo playing that originated with African slaves was preserved virtually unchanged in the isolation of the mountains, and makes a resurgence every summer at The Old Fiddlers’ Convention[4].

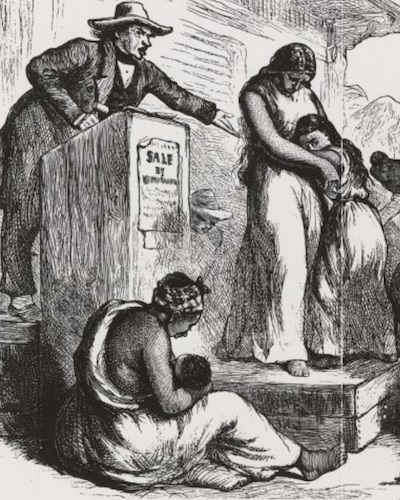

As the century progressed, the cotton gin made slavery more profitable for farmers in the south. The export of cotton in South Carolina went from 9,840 pounds in 1795 to 50 million pounds in 1810 and this increase in productivity meant an increase in slave labor (Furman, 18). Some Baptists formed abolitionist groups like the grandly named “Baptized Licking-Locust Association, Friends to Humanity” antislavery society in Kentucky (Leonard, 268).[5] But far too many Baptists in the west and north ignored the evils of slavery for the sake of American Baptist unity and many more embraced it for economic gain. The Triennial Convention of Baptists, where the state representatives met to debate all things Baptist, craved the financial support southern churches gave to the newly formed Foreign Mission Board (McBeth, 384). Baptists in leadership across the country, warned that anti-slavery talk would offend white slaveholders who might resist their evangelical efforts. Baptists were faced with a choice: act to change what went against the word of God, or act to change the interpretation of the word of God. South Carolina slave owner and Triennial president, Rev. Richard Furman, went so far as to preach that the Bible condoned slavery, and that those who opposed it were “unrighteous” (Furman, 26).

“Baptists in leadership across the country, warned that anti-slavery talk would offend white slaveholders who might resist their evangelical efforts. Baptists were faced with a choice: act to change what went against the word of God, or act to change the interpretation of the word of God.”

After slave uprisings like the ones led by Denmark Vessey in 1822 and Baptist preacher Nat Turner in 1831, state governments forced black churches of all denominations to merge with white congregations or face closure. Balconies were reserved for enslaved members who had received their master’s permission to attend church. Other churches like First Baptist Petersburg, Virginia, were legislatively compelled to replace their black minister with a white minister. The unexpected result was that most antebellum churches were integrated– but not equal (Leonard, 263-264 and Luqman-Dawson, 35).

An oft-preached passage of these integrated churches was Paul’s admonition to slaves in the church at Ephesus to obey their masters. Though out of context, it was a convenient proof text for those wishing to justify or ignore slavery and began an obsession with all things Paul in the evangelical church that is still with us. Even John Leland moderated his earlier antislavery views and admonished slaves to be obedient until God delivered them. If their deliverance didn’t work out, he looked forward to hearing their “melodious voices” in heaven which, considering Leland was against any overt action by the government, abolitionists or the slaves themselves, amounted to little more than an early take on “Shut up and sing” (Gourley).

Edward Matthews, a British abolitionist and Baptist minister visiting the United States witnessed first hand the perverted result of Baptist toleration of slavery. He tells of meeting an enslaved woman whose daughters were being sold south by their common master. This woman and her owner were both members of the same church in Kentucky. The church saw nothing wrong with the sale.“ America’s greatest curse,” Matthews wrote, “is a slave holding religion” (Matthews, 13, 20).

Bibliography

Blumenthal, Sidney. A Self-Made Man: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln Volume 1, 1809-1849. Simon and Schuster, New York, 2016.

Conway, Cecelia. African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia: A Study of Folk Traditions. U of Tennessee Press, 1995.

Epstein, Dena J. Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War. U of Illinois Press, 2003.

Giddens, Rhiannon, “Community and Connection,” IBGM Keynote Speech, 2017.

Gourley, Bruce. John Leland: Evolving Views on Slavery 1789-1839. “Baptist History and Heritage Journal. http://www.brucegourley.com/writings/lelandslavery1.htm

Inscoe, John C. (Ed.) Appalachians and Race: The Mountain South from Slavery to Segregation. UP Kentucky, 2001.

Leonard, Bill. Baptist Ways: A History. Judson Press, 2003.

Luqman-Dawson, Amina. African-Americans of Petersburg. Arcadia, Charleston, 2008.

Marks, Ben. “Strumm’n On the Old Banjo: How an African Instrument Got a Racist Reinvention.” Collector’s Weekly. October 4, 2016.

McBeth, H. Leon. The Baptist Heritage: Four Centuries of Baptist Witness. Broadman, 1987.

Matthews, Edward. The Shame and Glory of American Baptists: Or, Salveholders Versus Abolitionists, Thomas Matthews, Broad-Quay, Bristol, 1860.

Reiner, David and Peter Anick. Old Time Fiddling Across America. Mel Banks, 2015. Turnmire, Rebecca Elaine. “Worthy to be Classed?”: Slavery and it’s Legacy in Grayson County, Virginia.” Undergraduate Honors Thesis. William and Mary, 2013.

[1] The website, Musical Passage, recreates the music of enslaved Africans in 1688 Jamaica who had survived the Middle Passage. Hans Sloane, physician to the governor, published the musical transcription that provides the score for the recreation in his eyewitness account.

[2] Galax fiddling is closer to Scottish fiddling which is more percussive than the lilting Irish style of fiddling heard elsewhere in the area. Greenberry Leonard born 1810 was the premiere fiddler of his day and influential in the Galax style.

[3] Historian Ira Berlin, in Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America makes the distinction between societies with slaves, where slavery was limited, tangential to the economy and where slave and free spheres overlapped, and “slave societies” where slavery was at the center of the economy and all social interaction.

[4] The banjo technique called the “Galax lick” was never included in later minstrel manuals, neither was a variant banjo tuning most similar to one used with the halam in the Senegambian tradition. Both were directly transmitted to mountain whites from black players. (Conway 222, 236)

[5] No locusts were licked in the creation of this association. The name derives from two geographical locations in Kentucky. However, a Licking-Locust church was attended by a Thomas Lincoln, whose son, Abraham, would go on to say, “ If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think and feel” (Blumenthal, 25). He would later issue the Emancipation Proclamation freeing slaves in the south.