This is Part 2 of a series on Psalm 121. Part 1 is available here.

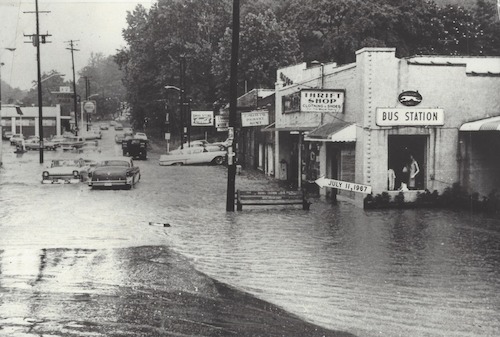

After a devastating flash flood in 1967, the Tennessee Valley Authority forced everyone to move away from the foothills of the Cumberland mountains and into the town of Oliver Springs. It was a seismic shift for the community. Both for those who lived up on the hill and were forced to leave their homes, and those who lived in town and lost their homes in the flood. My grandparents were among those who made the transition from hill to town, when they moved with their eight children from their three room house on the hill to a small house with six rooms in a neighborhood on the outskirts of Oliver Springs.

What made the house unique, aside from the indoor plumbing, was that while all the other houses on the street were built facing the gravel street that wound through the neighborhood, the house my grandparents moved into was built with it’s front porch facing back toward the hillside. The first owner oriented the house in that direction so that she could see her mother who lived in the hills behind the neighborhood. And, though the trees would eventually cover much of the hillside and obscure the abandoned homes, I like to think the sight of those hills was a source of comfort to my grandparents when they were feeling homesick or facing hard times.

In 586 Nebuchadnezzar defeated the forces of Israel and transported most of its inhabitants 1600 miles away to Babylon. It seems like a lot of trouble, but deporting whole populations was standard practice for victorious armies at that time. Originally developed by the Assyrians, the masters of messing with your mind, the goal was to disorient the captives by dissolving their connections to their homeland and to one another so that they were unable to unite and rebel. It worked so well for the Assyrians, who resettled over 4 million people in their day, that the Babylonians adopted the practice during their domination of the near east.

So, continuing our exploration of Psalm 121, it is no wonder then that the pat answer of verse 2 falls flat in the face of such momentous loss. Far from home and Jerusalem’s holy hill, the Jewish people had to express their faith in a new and more personal way. “The singing of songs was a crucial practice in the exilic period, “when the sacrificial rituals of the Temple were no longer available (Barton p219). Psalm 121 is thought to be one of the songs composed while in exile. In it, the individual must discover for herself a more expansive, more complete re-imagining of God.

The Hebrew Bible opens with, “in the beginning God created the heavens and the earth,” and yet this monumental statement no longer satisfies the speaker who feels alone in that creation. Deported to Babylon, the Israelites were introduced to the Babylonian creation epic, the Enuma Elish, wherein the divine protagonist, Marduk, combats the chaos caused by various and sundry gods and monsters and from their remains fashions an ordered universe. But for the composer of Psalm 121, there is no longer an ordered universe. The world seems to have returned to chaos. Where indeed can help come from in such circumstances? Where is God? What is God doing? What is God able to do, are questions we ask even now when the world appears out of control. And then in verse 3 comes the answer, “he will not let your foot be moved; he who keeps you will not slumber.”

The third verse of Psalm 121 begins what Walter Brueggemann refers to as the “move from a context of disorientation to a new orientation”. Just when all seemed lost, God intervenes with a new understanding or experience that shifts the psalmist’s perspective into “a new life-permitting and life-enhancing context where God’s way and will surprisingly prevail (Spirituality the of Psalms, p13).” God is re-defined not by what God has done in the past (in this case created) but what God will do in the future and is already doing in the life of the pilgrim. “He will not let your foot be moved,” promises verse 3. Here the distant “maker of earth” is so aware and involved in the journey of the individual that her foot will not stumble upon that earth that God has made.

Just as in the first verse in which the speaker lifts her eyes to watch for her coming help, the remainder of Psalm 121 details all the ways in which God is watching over the psalmist. So faithful is God’s attention, that God “neither slumbers nor sleeps” when guarding over Israel. This sleepless God is not a sentimental nanny hovering around her charges waiting to shuffle them out of harm’s way. Rather, the depiction of God as poised and ready to act, is a robust rebuttal to the fears and questions voiced in the opening of the psalm. The forces of chaos have not prevailed. God is alert and able on a grander scale. In the Enuma Elish, the Babylonian gods want nothing more than to sleep, and it is the duty of mankind to be ever vigilant to serve at the deities’ beck and call lest they arise from their rest and in the process unleash chaos (Batto, 162). But in an astounding reversal, the speaker discovers that the God of Israel is awake and ready to serve. The word translated “watch” appears six times in the Psalm and in the original Hebrew denotes an active guardianship in which the subject “exercises great care” over the object of their devotion. It’s the same word used when commanding God’s people to “guard the Sabbath and keep it holy” in Deuteronomy 5:12 (Becking, p8).

“The Lord is your keeper; the Lord is your shade at your right hand. The sun shall not strike you by day, nor the moon by night.”( verses 5,6) This is a God who is an active creator, who intervenes in the totality of the created world. God is present day and night taking care of the pilgrim as she journeys. Positioned at the right hand, a symbol of strength and blessing, the Lord oversees her physical health by offering shade from the sun during the heat of the day and, because some cultures at the time associated moonlight with madness, perhaps caring for her mental health as well when offering protection from the moon at night (Becking, 9).

“The Psalm highlights a new understanding of God, one that is richer and more complex than the Israelites had known prior to their exile and more powerful than what Babylon had to offer.”

Psalm 121 bookends the speaker’s initial question “Where does my help come from?” with the promise that “the Lord will watch over your coming and going.” God is not the distant, disinterested maker the speaker suspected in verse 2, but rather an ally deeply devoted to God’s people “now and forevermore.” The Psalm highlights a new understanding of God, one that is richer and more complex than the Israelites had known prior to their exile and more powerful than what Babylon had to offer. It is this new image of God that those who profess God’s Lordship must keep their eyes on going forward. And, rather than being defined by religious practice on a hill in Jerusalem, this new understanding is all about the relationship.

In the end it is to this caring, complex relationship with God that we must orient ourselves, even if it means as radical a shift as turning our entire metaphorical house around. Instead of focusing on the fear and calamity threatening to engulf us, we raise our eyes, not to tired tropes that no longer satisfy, but to the monumental truth that is our salvation. God is with us and God is for us. It is a mantra worth repeating, it is a breath prayer worth praying, it is a song worth singing as we journey toward home.

Bibliography

Barton, John Ed. The Hebrew Bible: A Critical Companion. Princeton UP, Princeton, 2016.

Batto, Bernard. “The Sleeping God: An Ancient Near Eastern Motif of Divine Sovereignty”

Becking, Bob. “God Talk for a Disillusioned Pilgrim in Psalm 121,” The Journal of Hebrew Scripture. Vol. 9. Article 15. Available online, here

Brueggemann, Walter. Spirituality of the Psalms. Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 2002. Available online, here.