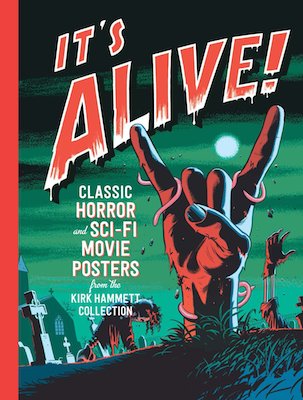

This time last year, when museums were open and we could move freely about the city, Todd and I took the girls to see “It’s Alive,” an exhibit at the Royal Ontario Museum featuring the classic horror and sci-fi movie poster collection of Metallica guitarist Kirk Hammett.

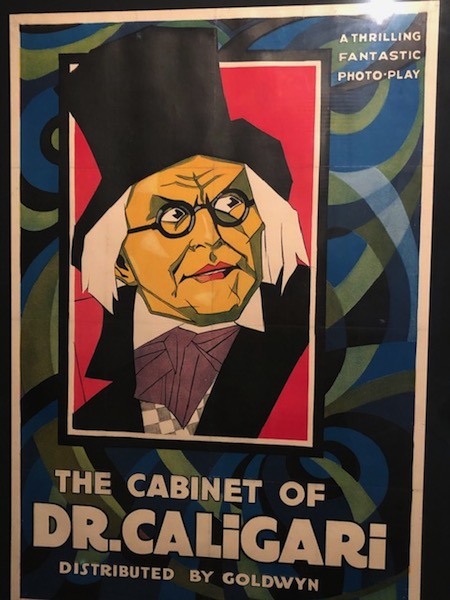

A collection like Hammett’s shouldn’t even exist. These movie posters were designed to be disposable. Their garish colors, emphatic fonts, and lurid images served to grab the attention of passers by and lure them into the theater. Once a film’s run ended, most posters, like those in the exhibit, were thrown out with the empty popcorn boxes. Fortunately, somewhere along the way someone thought to rescue these. The horror and sci-fi posters in “It’s Alive” ranged from artistic, to campy, to provocative. I remember seeing the 1920 film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in my college Cinema 101 class, and it was a treat to see the original poster in all its hypnotic, German expressionist glory.

With Halloween upon us, it’s fun to look back on this exhibit. However, beyond the artistic quality of the posters themselves, what interests me even more is what these posters and films had to say about their times and how they still speak to our own. Movies are a mirror for society. What we see on our screens is a reflection of, as well as commentary on, what is happening in our world. With the US election also upon us, there are important lessons to be found in these reflections.

From Dracula and Frankenstein to Godzilla and Barbarella, to contemporary counterparts like The Walking Dead, what these horror and science fiction movies all have in common is fear. Not the cinematic fear that comes from a well-placed jump scare or plot twist but the existential fear that lies outside a film’s celluloid frames. It’s the fear of the unknown, the fear of “the other”.

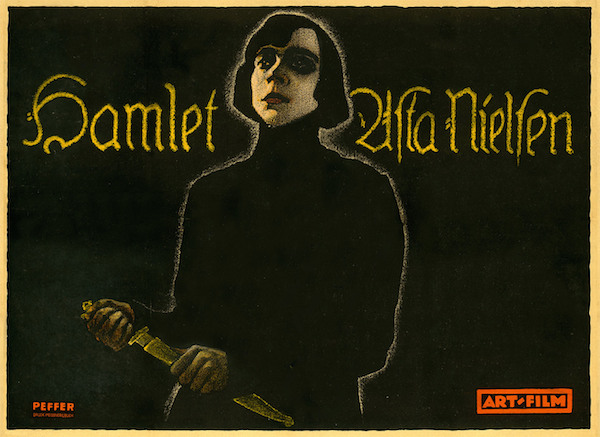

Sometimes this threat of “otherness” comes from within society. Jane Fonda’s image in the Barbarella movie poster physically dominates the composition and stands as a visual metaphor for the character’s confrontational feminism and sexuality, which, in 1968 (and, let’s face it, still today) posed a threat to traditional patriarchal structures. The ominous poster for the 1921 German film adaptation of Hamlet, which cast actress Asta Neilson in the titular role, vibrates with unspoken questions of gender and identity. Neither actress appears entirely at ease in her role, and that accompanying unpredictability only heightens the tension.

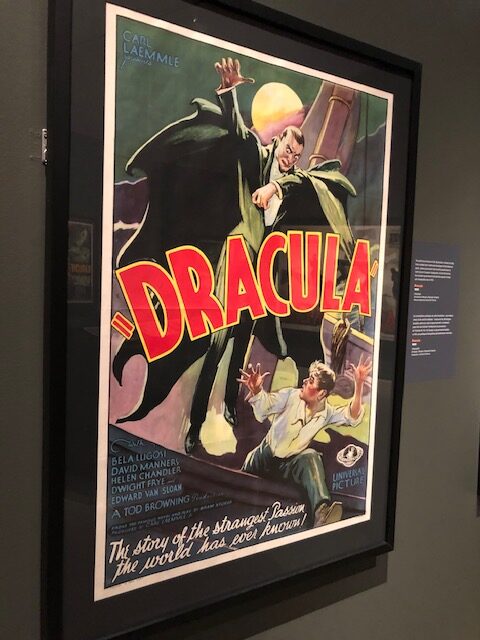

More often than not, however, in these films the threat of “the other” comes from outside or from the fringes of society. In the poster for the 1931 movie Dracula, the count looms menacingly over his intended victim while standing in a boat, suggesting he has just arrived from Transylvania, a detail not lost on American audiences at a time when the United States had recently passed laws to limit eastern European immigration. Other movie posters, like the one promoting King Kong (1933), borrowed heavily from a World War I recruiting poster depicting the German soldier as a savage ape carrying off Lady Liberty. Playing on Cold War era fears of an unseen enemy poised on the brink of invasion, 1950s films like The War of the Worlds (1953) replaced the marauding ape with flying saucers.

The casting of the zombie as the personification of otherness brings with it complex issues of race and class. “Zombies” first came to public consciousness through the writings of William Seabrook in the late 1920s. Seabrook was a white, American journalist in Haiti writing a book on voodoo during the American occupation of that country. As part of his research he visited the Haitian American Sugar Company where he was shown “zombies” at work. In reality these “zombies” were natives of Haiti forced to labor 18 hours a day in slave-like conditions for the company. Seabrook’s book caused a sensation when it hit the shelves in 1929 and soon after White Zombie (1932), with its Haitian voodoo-wielding villains, hit the theaters.

This practice of dehumanization is still very much alive. In a recent interview, political science professor Alexander Theodoridis, raises concerns about the power of “dehumanizing language” to change how we perceive one another. When President Trump calls someone an “animal,” it’s not long before his supporters start seeing that person as unworthy of respect or equal treatment. According to Theodoridis, this kind of thinking often leads to belief in conspiracy theories which further demonize the targeted group, and eventually may even lead to violence. For example, in the most recent presidential debate, when he was asked about the children who are being kept in detention at the border, President Trump immediately recast these children as the “other,” lumping them in with cartels, gangs and smugglers lurking along the southern border. Redefined as threats rather than as innocent victims, the Trump administration could then rationalize the policy of keeping these children in cages. And this is just one example from a President who has used dehumanizing language against women, immigrants, Muslim believers, the disabled, African American men and women, the LGBTQ+ community, and (not to be outdone by 1930s zombie racism) Haitians.

Our current President and Kurt Hammett’s movie poster collection present larger than life examples of how dehumanization and stoking the fear of the “otherness” works. The trouble is this stoked fear has everyday life consequences. We routinely treat “the other” as a problem rather than a person – at work, in school, on the street, even in church. We need a target at which to aim and direct our fear. This is especially disheartening to see in followers of Christ because, when we stop seeing the target of our outrage as beloved of God and made in the image of God, then we have stopped seeing them with the eyes of God as well.

“One way to counteract this urge to dehumanize is to re-humanize through empathy.”

One way to counteract this urge to dehumanize is to re-humanize through empathy. As digital creator Dylan Marron explains in his TED talk of the same name, “Empathy is not endorsement.” Marron turns trolling on its head by contacting individuals who have left negative and often dehumanizing comments about him on the internet and talking with them about the feelings behind their words. Marron finds he is usually able to find some common ground with his haters, such as a shared experience of high school bullying or (ironically) the shared experience of having a stranger make disparaging remarks about you in the comment section of a website. Of course, finding commonality doesn’t mean Marron or his adversary have to agree on everything, but the effort stops the slide into seeing people as problems rather than persons.

So, as we navigate the intensely polarized and partisan 2020 election, let us be aware of our own tendencies to problematize the other, and let us not shy away from calling out dehumanizing language when we hear it. One reason this election seems so scary is that, sadly, racism, classism, sexism, and a whole host of phobias that marginalize and discriminate against those God loves, are with us now as much as they ever were during the heyday of horror films. But we don’t have to propagate that hate. We can choose to live another way and leave the monsters to the movies.

Exhibit Catalogue:

Finamore, Daniel Ed. It’s Alive: Classic Horror and Sci-Fi Movie Posters from the Kirk Hammett Collection. Peabody Essex Museum Salem, MA 2017.

Dylan Marron’s Ted talk: “Empathy is Not Endorsement”