This is the fourth in a series of articles examining the parallels between the history of the Baptist church in America and the history of Old-Time String Band Music. Why it matters, here.

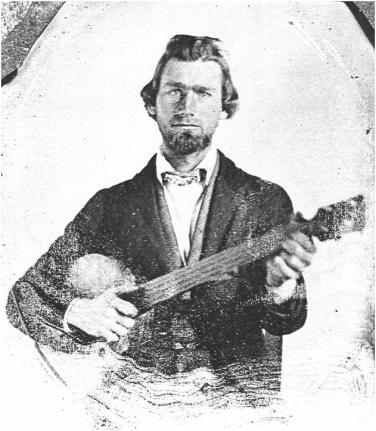

There were few slaves around Galax in the 1840s when Adam Manly Reece built himself a banjo and began learning tunes from black musicians. There weren’t that many more a few years later when he joined up with fiddler Greenberry Leonard and started the first string band of note playing the minstrel songs of Stephen Foster along with traditional fiddle tunes (Blue Ridge, 32[1]). And yet, when a Rev. Bacon came to town preaching that slavery was “man-stealing,” he was run off and narrowly escaped arrest (Matthews, 12). Only one percent of your average fiddle-playing farmers were slave owners in Grayson County, but a whopping seventy percent of justices, sheriffs, elected politicians, militia, and other officials in this area of the mountain south, owned enslaved people. Those in power owned the slaves, and those who wanted power, or endorsed those who held it by voting for them, bought into the system (Turnmire, 21, 37).

As potential tensions over the issue of slavery heightened, the original Baptist big tent of neutrality was looking more and more frayed[2]. It was neutral in the way that church members might appear to agree in a business meeting, but then out in the parking lot express totally different opinions. The debate in the “parking lot of public opinion” had been going on for quite some time with Baptist leaders on both sides of the slavery issue publishing open letters in Baptist newspapers. Leadership of the Triennial Convention lurched between abolitionists and slaveholders, with several splinter groups leaving to form parallel organizations more committed to ending slavery.

An address, circulated in 1841, stated that the purpose of the Mission Board was “missions and evangelism”, therefore “slavery was a topic beyond its distinct purpose,” and the board enforced this judicious stand with zeal. When the Georgia Baptists presented slave owner James Reeve as a candidate for mission service in 1844, they were looking for a fight. However, the Home Mission Board refused to take the bait. To remain neutral they could not appoint or reject Reeves, so they declined to receive his application on the grounds of, “introducing the topic of slavery, ” into their “deliberations”[3] (Richards, 24). It was, perhaps, not the most deft of maneuvers and it certainly didn’t fool the neighboring Alabama Convention which pushed for a more definitive ruling. Eventually the board reluctantly released a statement that missionaries with slaves would not be appointed. The Foreign Mission Board tepidly agreed with this policy still fearing the loss of financial support from southern states (Leonard,188 and Richards 25). With little to unify it, and lacking a principled stand to elevate it, the fraying “big tent” began to collapse.

In 1845 Baptists from Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia pulled up their stakes and formed their own pro-slavery missions organization, the Southern Baptist Convention. It was ironic that an organization like the Triennial Convention, formed to help churches more effectively conduct mission work, would split over the appointment of missionaries. Not that the SBC ever mentioned, “slavery” in its founding document. Like a southern apologist arguing that the Civil War was fought over “states’ rights” the SBC’s first president, William Johnson, framed the schism as a disagreement over “missionary rights” (Leonard, 189). That this was the right to appoint missionaries who owned slaves was conveniently ignored for the next 150 years. I grew up in a Southern Baptist Church, even took a class with the adults when I was in high school on “what it meant to be Baptist,” and never learned that to a great many people in the 19th century what being Southern Baptist meant was being pro-slavery.

“The SBC’s first president, William Johnson, framed the schism as a disagreement over “missionary rights”. That this was the right to appoint missionaries who owned slaves was conveniently ignored for the next 150 years.”

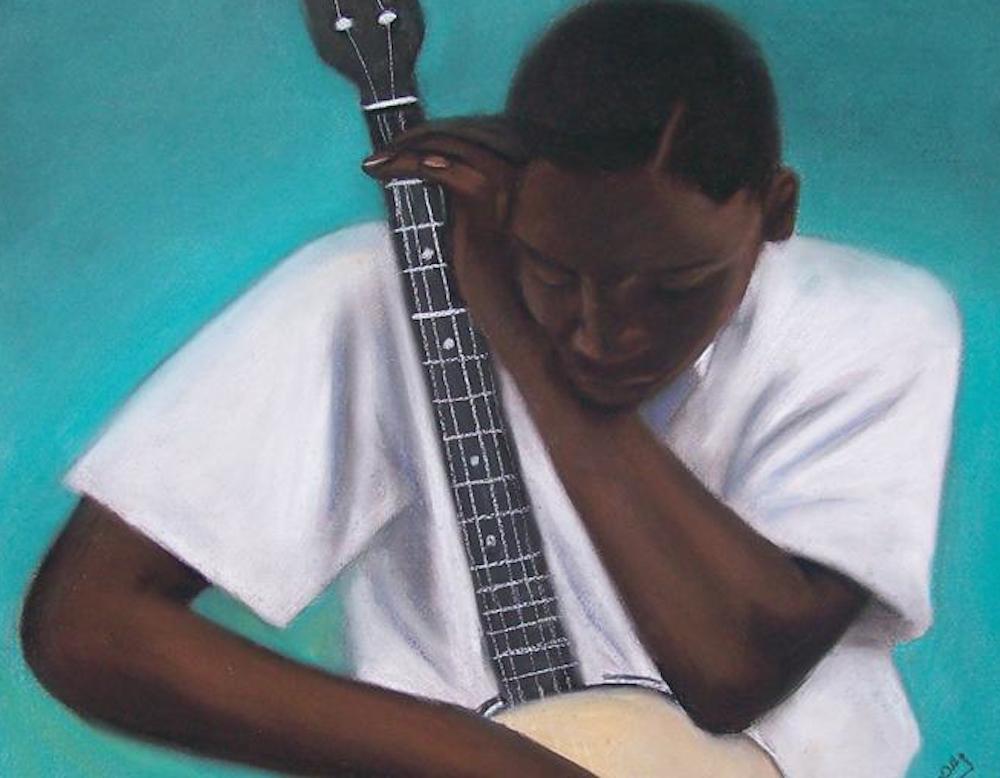

Just as Johnson obscured the history of the SBC’s origins, white musicians would redact the history of the banjo. Along with banjo manufacturers, they sought to “elevate” the banjo by “rescuing” it from black musicians and recasting it as an instrument befitting the parlor and “the most intelligent ladies and gentlemen.[4]” It wasn’t long before many banjo performers, teachers, and makers obscured or denied the instrument’s African roots entirely (Meredith, 51). Part of their motivation for this deception was monetary. Another, like the SBC’s recreation of its origin story, was an attempt to redefine their identity. Banjoists sought to portray the banjo as the preeminent “American” instrument, a rival to the European classical tradition. In their minds, purely “American” meant purely white, so they worked hard to assure admirers that slaves were incapable of playing such a complex instrument and that any plantation associations attached to the banjo were a mere “theatrical fantasy.” The racism in these arguments is blatant, but equally troubling is the willingness of a populace to ignore the evidence before them, and support such bald-faced lies (Mark).

The success of this relationship cannot be denied. Contemporary banjoist, Jake Hoffman, confesses that he came to the knowledge of the banjo through “white music.” “Minstrelsy,” he goes on to say, “ ripped the banjo out of black history and appropriated so deeply into white culture, that by the time that I came across it, I thought of it as the preeminent symbol of rural whiteness, and the tool for the white underdog to express his feelings in song”(TEDDirigo). Hoffman could be speaking for most Americans whose primary exposure to the banjo was through “The Beverly Hillbillies,” “Deliverance,” and “Hee-Haw.” Historian Laurent Dubois argues that the banjo is, “not just a sonic object but a cultural symbol. There’s probably no instrument in the world that’s had more stuff projected onto it, ” and that this position as a cultural symbol is what makes the banjo so powerful (Marks).

So the examination of the history of the banjo, and old-time string band music, may provide us with a powerful tool to challenge the culture seeking to define it.

Bibliography

Blue Ridge Music Makers Guild, Music Makers of the Blue Ridge Plateau. Arcadia, 2008.

Kafari, and Jake Hoffman. “Bones and Banjo: Confronting Cultural Appropriation,” TEDDirigo, December 20, 1917.

Kelley, Blair L.M. “A Brief History of Blackface,” The Grio. October 30, 2013.

Linn, Karen. That Half- Barbaric Twang: The Banjo in American Popular Culture. U of Illinois Press, 1994.

Marks, Ben. “Strumm’n On the Old Banjo: How an African Instrument Got a Racist Reinvention.” Collector’s Weekly. October 4, 2016.

Matthews, Edward. The Shame and Glory of American Baptists: Or, Salveholders Versus Abolitionists, Thomas Matthews, Broad-Quay, Bristol, 1860.

Meredith, Sarah. With a Banjo on Her Knee: Gender, Race, Class, and the American Classical Banjo Tradition, 1880-1915. Florida State Libraries. 2003.

Richards, Rogers Charles. Actions and Attitudes of Southern Baptists Towards Blacks: 1845-1895. Florida State University Libraries, 2008.

[1] Foster’s “Oh Susanna” was a sentimental adaptation of a slave ballot with similar lyrics published in an abolitionist journal. After all, the only way the song’s protagonist, a black man, is going to travel from Alabama to Louisiana in the 1840s was as a slave. Banjos were played by enslaved musicians at slave auctions and to accompany the journeys of slave coffels. This song was popularized by the Christy Minstrels (Marks).

[2] The New School Methodists in 1837 and the Presbyterians in 1844 had both split over the question of slavery.

[3] It was the Fight Club philosophy. “The first rule of avoiding the subject of slavery, is not to talk about slavery.” Georgia Baptists broke this rule because Reeves was a known slaveholder.

[4] According to the Waldo Manufacturing Company, far from being an African instrument, the banjo was in truth the European “banjeaux” (Linn, 12, 20).