I turned on my car radio a week ago Tuesday morning, anxious to hear details about the grand jury decision in the Michael Brown case. The BBC News Hour was on. I grunted. I love the BBC, but Ferguson analysis was probably not going to be their focus. Still, I decided to stay tuned in hopes that a Ferguson report would be forthcoming.

A commentary about Pope Francis’ address to the European Parliament was concluding with a woman commending the Pope for criticizing the EU’s indifference to African asylum seekers drowning in the Mediterranean. The broadcast then segued to Egypt, where an eight-story building had collapsed, killing at least fifteen people and injuring many more. Family, friends, and neighbors were frantically digging through the wreckage. The building was originally constructed with three stories, but the owner had added five additional floors supported with rickety wooden beams and other inadequate (and inexpensive) materials. Local authorities condemned the building three years ago, yet it remained standing. Those same authorities had instructed the occupants to move, but when the demolition order went unenforced, many of them stayed. Most didn’t have anywhere else to go.

In the end, I didn’t hear the Ferguson report I had tuned in to hear until the BBC News Hour went off the air. More than a week later, I (like you, no doubt) have read, seen, and heard more commentaries (and memes) on the grand jury decision not to indict Officer Darren Wilson than I can count. Now, another grand jury has refused to indict yet another officer, Daniel Pantaleo, in the choking death of yet another unarmed African-American, Eric Garner, and commentaries (and memes) are flooding the airwaves once more.

Adding one more entry to this already bulging catalog seems redundant and perhaps unnecessary at this point, but I want to offer three observations connected to the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner because those few happenstance minutes I spent listening to the BBC a week ago Tuesday morning have stuck with me. They changed my perspective on the racial unrest in America and the state of our world. I wonder if they might influence your perspective as well.

I. Ferguson is particular, not exceptional.

The racial dimensions of the Brown case, especially the dynamics between the police and the African-American community, are specifically American. The number of Black men shot by police in America is likewise alarming. Nevertheless, the despair, anger, and confusion surrounding the death of Michael Brown (and so many others like him) is not unique to this American tragedy. That same despair, anger, and confusion can be seen surrounding the rubble where an Egyptian apartment building stood just the other night, as well as surrounding the ripples in the water where a raft full of African migrants floated just moments ago.

This pain has its genesis in the great divides that exist in our world between the rich and the poor, the advantaged and disadvantaged, the powerful and the powerless. Some will argue that the world has always been in such a state, and it will always be. Perhaps. But that gap has had varying degrees of width and depth throughout history, and we are living in an era when the gap is widening and deepening precipitously.

The explosive community response in Ferguson is fueled by so much more than the death of Michael Brown, or even racial bias in policing. It is about the marginal place that African-Americans still occupy in American society fifty years after the Civil Rights movement. It is about inequality in housing, education, employment, and opportunity. It is about unequal treatment under the law (on the streets as well as in the courts) that is both a symptom of this systemic marginalization and a means of perpetuating it. The pent-up rage of this marginalization is now reaching a breaking point.

And the social pavement isn’t just cracking here in America. If we take a step back, we can see that the protests in Ferguson are the latest in a series of demonstrations against gross disparity stretching back to the economic collapse of 2008-09, a collapse that has multiplied the fortunes of the rich and maimed the economic prospects of virtually everyone else. The young and minorities have been especially hard hit across the globe. From Occupy Wall Street in New York, to Moral Mondays in North Carolina, across the Atlantic to Europe (particularly Spain and Greece), North Africa, the Middle East (the Arab Spring) and on to Asia (Myanmar) protests and uprisings continue to erupt. Some have succeeded in prompting change; many have not. But we, as a society, should take note of this trend – and those who wish to change society for the better should draw courage and inspiration from it. We are not standing alone.

II. We who are privileged do not understand this pain.

The news is unsettling. The images are heart wrenching. We sense something is wrong. We even bristle that “things” are so unjust. Then the waiter brings our drinks and we get on with our dinner.

We are ignorant, my fellow Americans of privilege: we who were born with white skin, who have connections and careers and “success,” especially those of us who are triply fortunate to have white skin, a good job, and a Y chromosome.

The wine of privilege from which we drink is a blend, not a vintage (despite all the labeling and marketing to the contrary). Privilege is always mixed with ignorance – no matter how many degrees we’ve earned, how many books we’ve read, or how much sophistication we want to believe we’ve acquired – because we never have to ask the questions that our less-privileged brothers and sisters have to ask, or face the realities they have to face. One of the insulating features of privilege has always been the convenience of tuning out or turning off anything that is unappealing.

Consequently, as protests erupt in Ferguson, Staten Island, Europe, and other parts of the world, we need to understand that we don’t get it – no matter how much we might sympathize, or how informed we might be concerning the social, cultural, and legal precedent for the grand jury proceedings in Missouri, or Egyptian building codes, or European Union immigration policies. We do not get it! Try to imagine digging through the debris of that collapsed apartment building for one of your relatives, or watching one of your friends crowd onto a makeshift raft to cross the Mediterranean, or knowing Michael Brown as a neighbor rather than a face on a placard. I can’t – not really.

The pain of social mariginalization radiates from a source that is simply outside the visible spectrum of our life experience. To our eyes, Ferguson and the other uprisings of the marginalized are the socio-political equivalent of ultra violet. We can really only ever understand them indirectly, and sadly we don’t seem to pay much attention until the desperation of the marginalized starts to burn this fair, privileged skin of ours. Then, of course, we decry those who riot, torch cars, and loot stores. We denigrate and dismiss them as miscreants and thugs. We cannot comprehend why anyone would do such things. We do not get it!

“The pain of social mariginalization radiates from a source that is simply outside the visible spectrum of our life experience. To our eyes, Ferguson and the other uprisings of the marginalized are the socio-political equivalent of ultra violet. “

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., can clue us in. He understood. As stalwart a champion and exemplar of non-violence as he was, he got it, because he lived a marginalized life.

…[I]t is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots. It would be morally irresponsible for me to do that without, at the same time, condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that exist in our society. These conditions are the things that cause individuals to feel that they have no other alternative than to engage in violent rebellions to get attention. And I must say tonight that a riot is the language of the unheard.

And what is it America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the negro poor has worsened over the last twelve or fifteen years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice and humanity. – MLK, “The Other America,” March 1968.

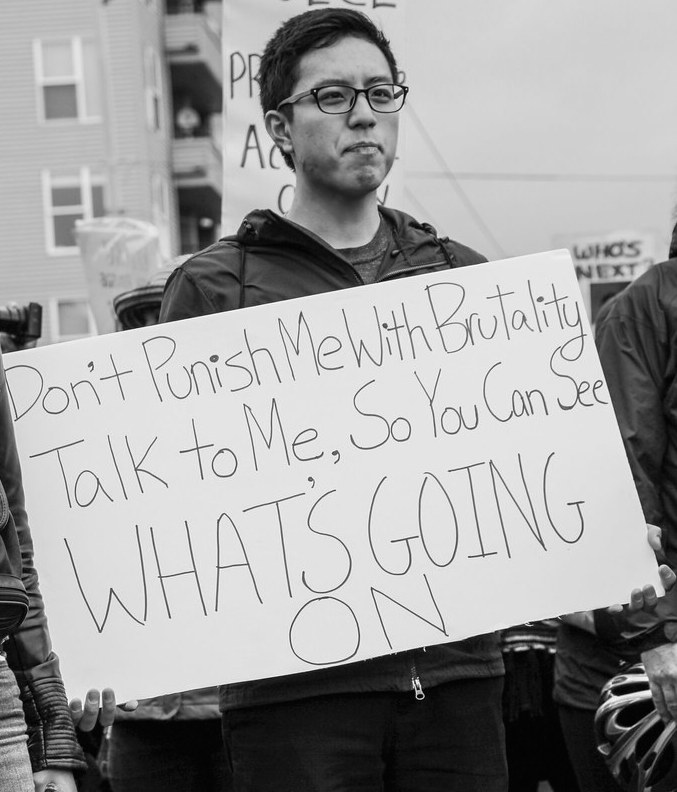

The people of Ferguson stood up to be heard in August, as many before them have stood up. The response they received was a grotesque display of force from the police and dismissal from the judiciary branch of their government. The message of this response is simple and clear: “We, who have power and privilege, are not listening to you – and we do not intend to listen.”

Until we admit our ignorance and are willing to listen, we won’t stand a chance of understanding what is currently transpiring in our world – even indirectly – and we consign America to remain merely a particular nation rather than the exceptional one we proclaim it to be. We also leave the marginalized with little choice other than to crack the social pavement until the foundations of the current social order begin to shift.

III. Even if we could understand, understanding wouldn’t be enough.

Commentaries, op eds, cable news shouting matches – all of these status quo forms of engagement seek to stake out a position and determine who and/or what is right, and who and/or what is wrong. None of it, even from the most reputable sources and the most astute minds, will help change the news being reported. Analysis is a piece of the puzzle, but solving the puzzle is the ultimate objective – and this puzzle won’t be solved with words or theories.

If we want to take an honest shot at solving the perplexing socio-political puzzle that is our present age, we have to seek more than understanding. We have to go further than analysis, commentary, or curiosity can take us. We need friendship. We need community and, ultimately, solidarity with those who are crying out. We need to listen, and we need to do more than listen; we need to allow the marginalized to teach us and guide us, and to help us see with their eyes. For that, we need their company not just their testimony.

“we need to allow the marginalized to teach us and guide us, and to help us see with their eyes. For that, we need their company not just their testimony.”

Seeing with their eyes also means coming down out of our intellectual orbit, and cutting through the atmosphere of our opinions, philosophies, and ideologies. Whether we agree or disagree with the grand jury decisions not to indict Darren Wilson and Daniel Pantaleo; whether we feel the police’s use of deadly force should be restricted or unrestricted; whether we see the political unrest in North Africa and the Middle East as a harbinger of hope or doom; whether we believe government stimulus or fiscal austerity is the best way to address our economic woes, we need to see that the reality on the ground, especially for the marginalized, is one where there is no peace.

There is no peace on the streets of Ferguson. There is no peace in Staten Island. There is no peace in Egypt or Spain or Afghanistan. And in theses places (not to mention many other neighborhoods of the world), peace left long before the demonstrations started.

How are we going to sow peace in these peace-less places?

That is the singular question before us as a nation and a global community, though there is no single answer. But however we answer it, we cannot do so using satellite imagery. We will have to grapple with it on the ground.

And so I want to challenge myself, my fellow Christians and their churches to crowd the front lines in asking, proposing, and living answers to this question, “how do we sow peace?” – especially if we are privileged. Some are already there, but more of us need to join them actively and intentionally. The front lines are where Christ calls us to be. If we consider ourselves children of God, then we must also answer to the name of peacemaker (Matthew 5.9) and peacemakers live and work where there is no peace. They lead by example. They do more than listen, pray, and discuss. They act.

In truth, this shouldn’t require any additional, special effort on our part. We are already commissioned for this work. If we are feeding the hungry, refreshing the thirsty, clothing the naked, caring for the sick, visiting the imprisoned, welcoming the stranger, loving our neighbors, and loving our enemies, peace should sprout and blossom in the wake of our presence.

So perhaps the first questions we need to ask are, “With so many churches around the world, why is peace not blooming in more places?” And, “As we head into the second week of Advent, the week of Peace, what are we as the people of Jesus going to do other than light a candle on the Advent Wreath and recite a litany?”

It’s time to do more than turn on the radio to stay informed. It’s time to do more than Tweet our support for equality. It’s time to turn out into the streets, to be a voice for the voiceless, to lend an ear to those who are not heard, and to receive guided tours of what life is like in the margins. It’s time to be peacemakers. It’s time to change the news, not the channel.

Christ calls us, and the world needs us.